Do schools and trees mix? You may have memories of shady playing areas and shelter belts by playing fields, but our recent study suggests this is increasingly an exception rather than a rule.

Trees are often seen as a health and safety risk, whether from branches or the whole thing falling, or from children falling out of them. Many schools have banned pupils from climbing trees as a result.

Beyond that, trees are often seen as an optional “nice to have”. New Zealand’s current education minister criticised extensive landscaping and bespoke design when announcing a review of school properties in early 2024.

But the benefits of trees and other vegetation in urban areas are well known, and increasingly important as housing density increases. Schools can play a significant role in encouraging the growth of “urban forests”.

Unfortunately, there are also large differences in tree canopy cover in New Zealand cities (and elsewhere in the world), with low socioeconomic areas often having low tree canopy cover.

This matters because trees and nature in general provide us with enormous health and wellbeing benefits, regardless of socioeconomic standing.

Natural benefits

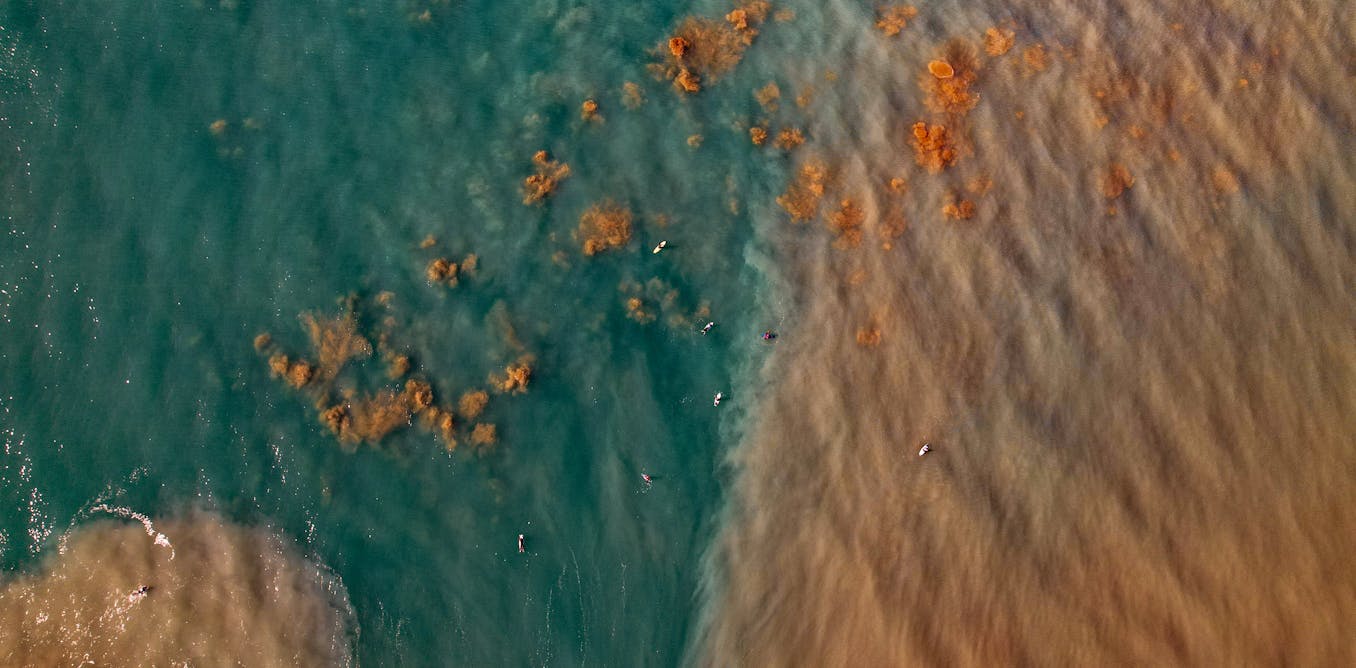

Very little is known about green spaces on local school grounds. So, our research set out to survey the quantity and quality of green spaces in 64 urban primary schools in Auckland.

We conducted the survey in the context of several known factors about the role and place of nature in education:

Because schools are fairly evenly distributed throughout cities, and can have a large spatial footprint, there’s also an opportunity to enhance wider native biodiversity, create ecological corridors and maintain cultural connections.

Getty Images

Fields but few trees

Unfortunately, our survey found the green spaces of most Auckland primary schools are dominated by sports fields.

While it’s good news that children have access to these, adding trees and shrubs around the edges of the fields could provide many benefits without compromising existing play spaces.

Native biodiversity was also lacking. In fact, 33% of school ground contained environmental weeds, such as woolly nightshade. There were also many more introduced plant species than native species, and most schools lacked a shrub layer.

Urban green spaces in general tend to favour single trees with mown lawn underneath. But birds feed in different layers of vegetation and need that shrub layer and some vegetation complexity.

The most common native tree by far was pōhutakawa. But planting a monoculture of pōhutakawa is a big risk if a disease (such as myrtle rust) has a big impact on that species.

Diversity is key. Planting other native species such as pūriri, karaka, rewarewa or tītoki would increase plant diversity, attract native birds and other species, as well as provide sun shade.

Room for improvement

There was some good news, however. Of the 64 schools surveyed, 36% had a forest patch. This gives the children access to an outdoor learning resource that may be lacking from their immediate neighbourhood.

It was heartening to find every school had at least one species associated with weaving, with both harakeke and tī kōuka present at 83% of schools.

We know young Māori in cities are at risk of losing cultural knowledge and opportunities for cultural practices, so the availability of key weaving species is an excellent opportunity for schools and their whānau.

If this was a report card, Auckland’s school green spaces would not be high-achieving. But there are plenty of opportunities to improve. Adding more diversity, more native plants, and planting trees around the edges of sports fields will provide a wealth of benefits to both children and the city’s overall biodiversity.

Using outdoor spaces for learning will increase natural and cultural connections and improve children’s wellbeing. That is much more than a “nice to have”.

The post “Does your school have enough trees? Here’s why they’re great for kids and their learning” by Margaret Stanley, Professor of Ecology, University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau was published on 01/29/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply