Snow leopards are known as the “ghosts of the mountains” for a reason. Imagine waiting for months in the harsh, rugged mountains of Asia, hoping to catch even a glimpse of one. These elusive big cats move silently across rocky slopes, their pale coats blending so seamlessly with snow and stone that even the most seasoned biologists seldom spot them in the wild.

Travel writer Peter Matthiessen spent two months in 1973 searching the Tibetan plateau for them and wrote a 300-page book about the effort. He never saw one. Forty years later, Peter’s son Alex retraced his father’s steps – and didn’t see one either.

Researchers have struggled to come up with a figure for the global population. In 2017, the International Union for Conservation of Nature reclassified the snow leopard from endangered to vulnerable, citing estimates of between 2,500 and 10,000 adults in the wild. However, the group also warned that numbers continue to decline in many areas due to habitat loss, poaching and human-wildlife conflict. Those who study these animals want to help protect the species and their habitat – if only we can determine exactly where they live and how many there are.

Traditional tracking methods – searching for footprints, droppings and other signs – have their limits. Instead of waiting for a lucky face-to-face encounter, conservationists from the Wildlife Conservation Society, led by experts including Stéphane Ostrowski and Sorosh Poya Faryabi, began deploying automated camera traps in Afghanistan. These devices snap photos whenever movement is detected, capturing thousands of images over months, all in hopes of obtaining a rare glimpse of a snow leopard.

But capturing images is only half the battle. The next, even harder task is telling one snow leopard apart from another.

Eve Bohnett, CC BY-ND

At first glance, it might sound simple: Each snow leopard has a unique pattern of black rosettes on its coat, like a fingerprint or a face in a crowd. Yet in practice, identifying individuals by these patterns is slow, subjective and prone to error. Photos may be taken at odd angles, under poor lighting, or with parts of the animal obscured – making matches tricky.

A common mistake happens when photos from different cameras are marked as depicting different animals when they actually show the same individual, inflating population estimates. Worse, camera trap images can get mixed up or misfiled, splitting encounters of one cat across multiple batches and identities.

I am a data analyst working with Wildlife Conservation Society and other partners at Wild Me. My work and others’ has found that even trained experts can misidentify animals, failing to recognize repeat visitors at locations monitored by motion-sensing cameras and counting the same animal more than once. One study found that the snow leopard population was overestimated by more than 30% because of these human errors.

To avoid these pitfalls, researchers follow camera sorting guidelines: At least three clear pattern differences or similarities must be confirmed between two images to declare them the same or different cats. Images too blurry, too dark or taken from difficult angles may have to be discarded. Identification efforts range from easy cases with clear, full-body shots to ambiguous ones needing collaboration and debate. Despite these efforts, variability remains, and more experienced observers tend to be more accurate.

Now people trying to count snow leopards are getting help from artificial intelligence systems, in two ways.

Spotting the spots

Modern AI tools are revolutionizing how we process these large photo libraries. First, AI can rapidly sort through thousands of images, flagging those that contain snow leopards and ignoring irrelevant ones such as those that depict blue sheep, gray-and-white mountain terrain, or shadows.

Eve Bohnett, CC BY-NC-ND

AI can identify individual snow leopards by analyzing their unique rosette patterns, even when poses or lighting vary. Each snow leopard encounter is compared with a catalog of previously identified photos and assigned a known ID if there is a match, or entered as a new individual if not.

In a recent study, several colleagues and I evaluated two AI algorithms, both separately and in tandem.

The first algorithm, called HotSpotter, identifies individual snow leopards by comparing key visual features such as coat patterns, highlighting distinctive “hot spots” with a yellow marker.

The second is a newer method called pose invariant embeddings, which operates similar to facial recognition technology: It recognizes layers of abstract features in the data, identifying the same animal regardless of how it is positioned in the photo or what kind of lighting there may be.

We trained these systems using a curated dataset of photos of snow leopards from zoos in the U.S., Europe and Tajikistan, and with images from the wild, including in Afghanistan.

Alone, each model worked about 74% of the time, correctly identifying the cat from a large photo library. But when combined, the two systems together were correct 85% of the time.

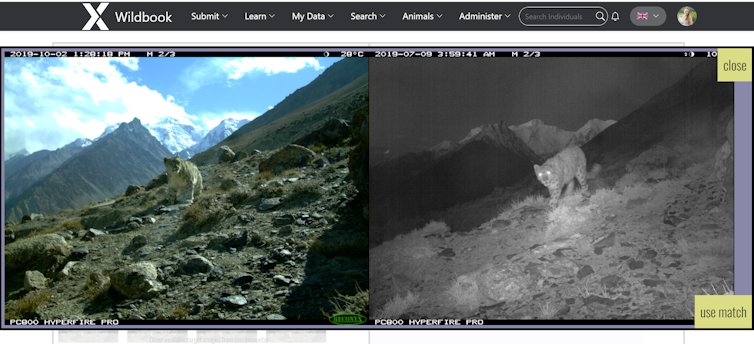

These algorithms were integrated into Wildbook, an open-source, web-based software platform developed by the nonprofit organization Wild Me and now adopted by ConservationX. We deployed the combined system on a free website, Whiskerbook.org, where researchers can upload images, seek matches using the algorithms, and confirm those matches with side-by-side comparisons. This site is among a growing family of AI-powered wildlife platforms that are helping conservation biologists work more efficiently and more effectively at protecting species and their habitats.

Wildbook/Eve Bohnett, CC BY-ND

Humans still needed

These AI systems aren’t error-proof. AI quickly narrows down candidates and flags likely matches, but expert validation ensures accuracy, especially with tricky or ambiguous photos.

Another study we conducted pitted AI-assisted groups of experts and novices against each other. Each was given a set of three to 10 images of 34 known captive snow leopards and asked to use the Whiskerbook platform to identify them. They were also asked to estimate how many individual animals were in the set of photos.

The experts accurately matched about 90% of the images and delivered population estimates within about 3% of the true number. In contrast, the novices identified only 73% of the cats and underestimated the total number, sometimes by 25% or more, incorrectly merging two individuals into one.

Both sets of results were better than when experts or novices did not use any software.

The takeaway is clear: Human expertise remains important, and combining it with AI support leads to the most accurate results. My colleagues and I hope that by using tools like Whiskerbook and the AI systems embedded in them, researchers will be able to more quickly and more confidently study these elusive animals.

With AI tools like Whiskerbook illuminating the mysteries of these mountain ghosts, we have another way to safeguard snow leopards – but success depends on continued commitment to protecting their fragile mountain homes.

The post “AI helps tell snow leopards apart, improving population counts for these majestic mountain predators” by Eve Bohnett, Assistant Scholar, Center for Landscape Conservation Planning, University of Florida was published on 06/18/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply