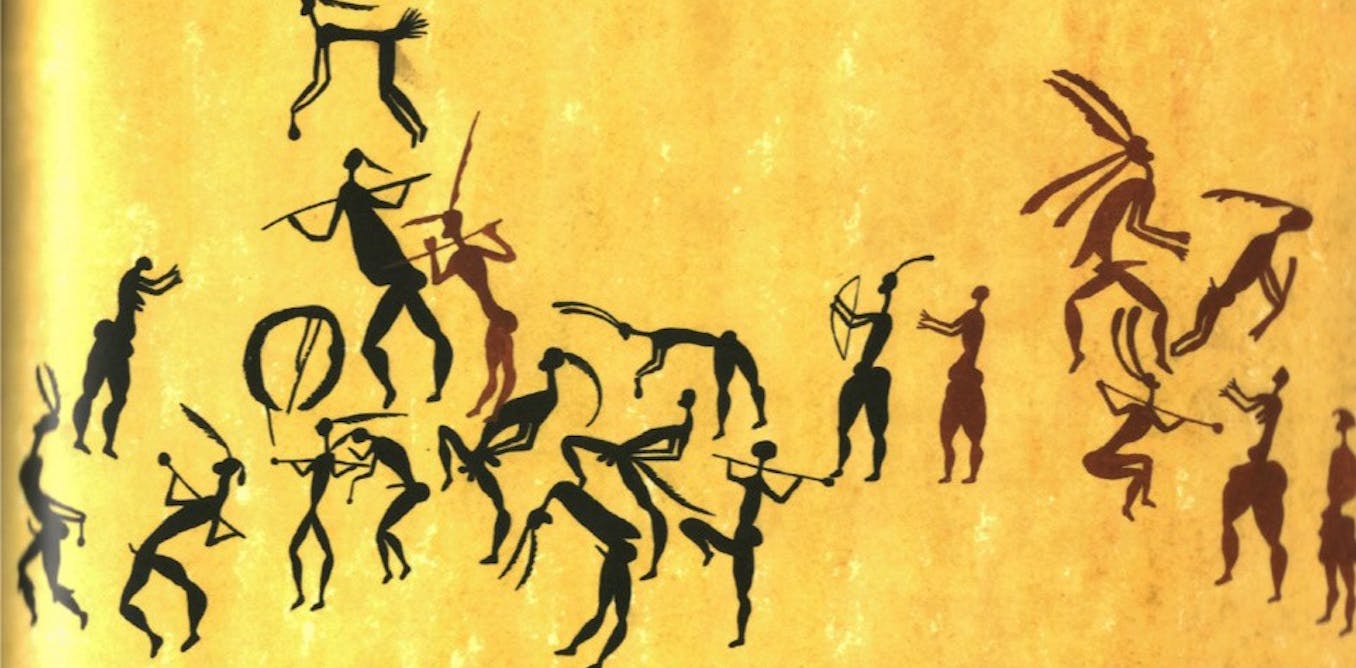

In ancient Athens, the agora was a public forum where citizens could gather to deliberate, disagree and decide together. It was governed by deep-rooted social principles that ensured lively, inclusive, healthy debate.

Today, our public squares have moved online to the digital feeds and forums of social media. These spaces mostly lack communal rules and codes – instead, algorithms decide which voices rise above the clamour, and which are buried beneath it.

The optimistic idea of the internet being a radically democratic space feels like a distant memory. Our conversations are now shaped by opaque systems designed to maximise engagement, not understanding. Algorithmic popularity, not accuracy or fairness, determines reach.

This has created a paradox. We enjoy unprecedented freedom to speak, yet our speech is constrained by forces beyond our control. Loud voices dominate. Nuanced voices fade. Outrage travels faster than reflection. In this landscape, equal participation is all but unattainable, and honest speech can carry a very genuine risk.

Somewhere between the stone steps of Athens and the screens of today, we have lost something essential to our democratic life and dialogue: the balance between equality of voice and the courage to speak the truth, even when it is dangerous. Two ancient Athenian ideals of free speech, isegoria and parrhesia, can help us find it again.

Ancient ideas that still guide us

In Athens, isegoria referred to the right to speak, but it did not stop at mere entitlement or access. It signalled a shared responsibility, a commitment to fairness, and the idea that public life should not be governed by the powerful alone.

The term parrhesia can be defined as boldness or freedom in speaking. Again, there is nuance; parrhesia is not reckless candour, but ethical courage. It referred to the duty to speak truthfully, even when that truth provoked discomfort or danger.

These ideals were not abstract principles. They were civic practices, learned and reinforced through participation. Athenians understood that democratic speech was both a right and a responsibility, and that the quality of public life depended on the character of its citizens.

The digital sphere has changed the context but not the importance of these virtues. Access alone is insufficient. Without norms that support equality of voice and encourage truth-telling, free speech becomes vulnerable to distortion, intimidation and manipulation.

The emergence of AI-generated content intensifies these pressures. Citizens must now navigate not only human voices, but also machine-produced ones that blur the boundaries of credibility and intent.

Read more:

The ancient Greeks invented democracy – and warned us how it could go horribly wrong

When being heard becomes a privilege

On contemporary platforms, visibility is distributed unequally and often unpredictably. Algorithms tend to amplify ideas that trigger strong emotions, regardless of their value. Communities that already face marginalisation can find themselves unheard, while those who thrive on provocation can dominate the conversation.

On the internet, isegoria is challenged in a new way. Few people are formally excluded from it, but many are structurally invisible. The right to speak remains, but the opportunity to be heard is uneven.

At the same time, parrhesia becomes more precarious. Speaking with honesty, especially about contested issues, may expose individuals to harassment, misrepresentation or reputational harm. The cost of courage has increased, while the incentives to remain silent, or to retreat into echo chambers, have grown.

Read more:

Social media can cause stress in real life – our ‘digital thermometer’ helps track it

Building citizens, not audiences

The Athenians understood that democratic virtues do not emerge on their own. Isegoria and parrhesia were sustained through habits learned over time: listening as a civic duty, speaking as a shared responsibility, and recognising that public life depended on the character of its participants. In our era, the closest equivalent is civic education, the space where citizens practise the dispositions that democratic speech requires.

By making classrooms into small-scale agoras, students can learn to inhabit the ethical tension between equality of voice and integrity in speech. Activities that invite shared dialogue, equitable turn-taking and attention to quieter voices help them experience isegoria, not as an abstract right but as a lived practice of fairness.

In practice, this means holding discussions and debates where students have to verify information, articulate and justify arguments, revise their views publicly, or engage respectfully with opposing arguments. These skills all cultivate the intellectual courage associated with parrhesia.

Importantly, these experiences do not prescribe what students should believe. Instead, they rehearse the habits that make belief accountable to others: the discipline of listening, the willingness to offer reasons, and the readiness to refine a position in light of new understanding. Such practices restore a sense that democratic participation is not merely expressive, but relational and built through shared effort.

What civic education ultimately offers is practice. It creates miniature agoras where students rehearse the skills they need as citizens: speaking clearly, listening generously, questioning assumptions and engaging with those who think differently.

These habits counter the pressures of the digital world. They slow down conversation in spaces designed for speed. They introduce reflection into environments engineered for reaction. They remind us that democratic discourse is not a performance, but a shared responsibility.

Returning to the spirit of the agora

The challenge of our era is not only technological but educational. No algorithm can teach responsibility, courage or fairness. These are qualities formed through experience, reflection and practice. Athenians understood this intuitively, because their democracy relied on ordinary citizens learning how to speak as equals and with integrity.

We face the same challenge today. If we want digital public squares that support democratic life, we must prepare citizens who know how to inhabit them wisely. Civic education is not optional enrichment – it is the training ground for the habits that sustain freedom.

The agora may have changed form, but its purpose endures. To speak and listen as equals, with honesty, courage and care, is still the heart of democracy. And this is something we can teach.

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

The post “What ancient Athens teaches us about debate – and dissent – in the social media age” by Sara Kells, Director of Program Management at IE Digital Learning and Adjunct Professor of Humanities, IE University was published on 12/02/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply