Geoffrey Chaucer’s Miller’s Tale is renowned for its salacious storyline of sexual misadventure. Set in 14th-century Oxford, it tells the tale of John the Carpenter, a husband so terrified that another “Noah’s flood” is coming to drown the world that he sleeps in a basket in the attic – freeing his wife to bed her lover downstairs.

Chaucer’s pilgrims all have a good laugh at John’s expense as they walk together from London towards Canterbury, echoing John’s neighbours who “gan laughen at his fantasye” of Noah’s flood and call John “wood” (mad). The pilgrims listen to this particular tale (one of 24 Canterbury Tales) as they walk along the south bank of the River Thames between Deptford and Greenwich.

That stretch of river was well-known to Chaucer. At the time of writing what remains one of English literature’s greatest works, he had been tasked, in March 1390, with repairing flood damage to the riverbank around Greenwich.

As a poet who swapped his pen for a spade to dig banks and defend the land around Greenwich from inundation, Chaucer knew from experience that flooding was no laughing matter. He – and later Shakespeare – lived through periods of weird weather not unlike what we are seeing today.

Their changing climate was triggered by falling rather than rising temperatures during what’s known as the little ice age. But the net effect was weather extremes like strong winds, storms and flooding – some of which were evoked in plays, prose and poems, offering valuable information on how communities were hit by, and responded to, these extreme events.

For the past two years, I have been scouring historical literature and performances for – now-often forgotten – experiences of living with water and flooding along the shorelines and estuaries of England’s coastlines. Whether in 15th-century “flood plays” in Hull or the “disaster pamphlets” (an early form of newsbook) that rose to popularity in Shakespeare’s lifetime, my research shows we do not only need to look to the future to understand the challenges posed by rising seas and more intense storms.

British Library via Wikimedia

Hull’s medieval flood play

Early in the new year of 1473, a crowd gathered outside Kingston-upon-Hull’s main church to watch the annual flood play performed. The play itself is now lost, but surviving records cast tantalising light on how the play was staged between 1461 and 1531. We know, for example, it was snowing in 1473 because of a payment that year for “makyng playne the way where snawe was”.

We also know from financial records that the play was performed on an actual ship, hauled through Hull’s streets on wheels and hung on ropes for the rest of the year in Holy Trinity church (now Hull Minster). We know from payments to “Noye and his wyff”, “Noyes children” and “the god in the ship” that the play must have told a very similar story to that of two medieval pageants still performed today in the neighbouring east coast city of York.

What is not immediately clear from Hull’s records is why the town’s guild of master mariners chose the snow and ice of early January as the annual date for their flood play’s performance, when biblical plays in York and other northern towns and cities were staged during the warmer months of Easter and midsummer. A payment for Noah’s “new myttens” in 1486 speaks to the challenges of performing outdoor theatre in January, typically the coldest time of year.

In fact, Hull’s flood play was always staged on Plough Monday, the first Monday after the Christian celebration of Epiphany on January 6. This date marked the traditional start of the new agricultural year, and a close reading of Hull’s records shows themes of farming woven into the flood play. The benefits of flooding for haymaking, for example, were signalled on stage through the purchase of agrarian items like a “mawnd” (grain basket) in 1487, “hay to the shype” (ship) in 1530, and plough hales (handles) “to the chylder” (children) in 1531.

Ferens Art Gallery via Wikimedia

The advantages of flooding meadows had long been recognised in the Humber villages surrounding Hull – and reflected in the layout of its medieval land. Grass grew well on the well-drained meadows along the River Humber’s banks, and the hay harvested from these floodplains provided winter feed for farm animals including the oxen that pulled ploughs through arable fields in January, at the start of the new agricultural year.

Writing and water management were once familiar bedfellows – and the wisdom of building raised flood banks and making hay on floodplains is reflected throughout medieval and early modern literature.

Writing of Runnymede, an ancient meadow on the banks of the River Thames, in his 1642 poem Coopers Hill, John Denham casts an approving glance on the “wealth” that the seasonal flooding of the Thames brings to the meadows on its river banks: “O’re which he kindly spreads his spacious wing / And hatches plenty for th’ensuing Spring.”

But Denham distinguishes between two types of flood: the benevolent, seasonal kind that brings wealth to the meadows, and the “unexpected Inundations” that “spoile the Mowers hopes” and “mock the Plough-mans toyle”. Floods can bring disaster if they are unexpected (for example, if they occur during the growing season in spring and summer) or out of place (flooding arable fields rather than meadow ground). But literature reminds us they can also bring benefits – if communities learn to live with water and adapt their lives to the rising tide.

Unfortunately, despite renewed interest in nature-based solutions to flood alleviation, floodplain meadows declined sharply in the 20th century and few exist today. Downstream of Runnymede, at Egham Hythe, is Thorpe Hay Meadow. Once part of a thriving medieval economy of haymaking on floodplains, its website announces it is now the “last surviving example of unimproved grassland on Thames Gravel in Surrey”.

Gone too are Hull’s meadows and its flood play, which once celebrated the benefits of flooding for farming in this stretch of north-east English coastline. Some of the meadows in the village of Drypool, directly to the east of Hull, were built on as early as the 1540s for Henry VIII’s new defensive fortifications. Much of the remainder was absorbed into this industrial city’s urban sprawl from the 17th century onwards. Today, the Humber’s banks in urban Hull are heavily defended by a £42 million concrete frontage, protecting all the homes and businesses on the floodplain beyond.

Royal Museums Greenwich via Wikimedia, CC BY-NC

Shakespeare’s storms

Shakespeare was born in 1564 into one of the coldest decades of the last millennium. Temperatures plunged across northern Europe in the 1560s, and the winter of 1564-5 was especially severe.

The little ice age brought shorter springs and longer winters to northern Europe. Reconstructed temperatures show the climate was on average between 1 and 1.5°C colder during Shakespeare’s lifetime than our own. But it was also an age of weather extremes, bringing heat and drought alongside snow and ice.

The weather diary of Shakespeare’s almost exact contemporary, Richard Shann (1561-1627), now housed in the British Library’s manuscripts department, is an invaluable witness to these fluctuating extremes. Writing from the village of Methley in West Yorkshire, Shann describes “a could and frostie winter” in 1607-8 “the like not seene of manie yeares before”. Indeed, the frost “was so extreame that the Rivers was in a manner dried up”.

At York, Shann writes, people “did playe at the bowles” on the river Ouse, and in London “did builde tentes upon the yse” (ice). Temperatures soared that summer, with July 1608 “so extreame hote that divers p[er]sonnes fainted in the feilde”. But the cold quickly returned. “A verie great froste” was reported as early as September 1608, with Shann reporting that the River Ouse “would have borne a swanne”.

The climate crisis has a communications problem. How do we tell stories that move people – not just to fear the future, but to imagine and build a better one? This article is part of Climate Storytelling, a series exploring how arts and science can join forces to spark understanding, hope and action.

As the weather became more variable, with hot and cold spells more extreme, so the late 16th and 17th centuries saw an increase in the frequency and intensity of storms – such that this era has been dubbed “an age of storms”.

On Christmas Eve 1601, Shann describes “such a monstrous great wynde” in Methley “that manie persons weare at theyr wittes ende for feare of blowinge downe theyre howses”. After the storm causes the River Aire at Methley to flood, he writes of his neighbours that the water “came into theyre howses so high, that it allmost did touch theyre chambers”.

In London, meanwhile, historian John Stow (1525-1605) records extremes of heat and cold leading to storms and floods throughout the 1590s. In his Annals of England to 1603, Stow reports “great lightning, thunder and haile” in March 1598, “raine and high waters the like of long time had not been seene” on Whitsunday 1599 – and in December 1599, “winde … boisterous and great” which blew down the tops of chimneys and roofs of churches. The following June, there were “frosts every morning”.

The storminess of this period also appears to seep into Shakespeare’s work. Several of his later plays use storms at sea as plot devices to shipwreck characters on islands (The Tempest) or distant shores (Twelfth Night). In Pericles, Prince of Tyre, Shakespeare (the co-author, with George Wilkins (died 1618)) tosses his hero relentlessly across the eastern Mediterranean in a play that features no fewer than three storms at sea.

While many of Shakespeare’s storms take place in distant locations and at sea, King Lear sets the storm which rages throughout its central scenes in Kent, on the English east coast. Lear describes “the roaring sea” and “curlèd waters” that threaten to inundate the land. It is a play shaped by the east coast’s long experience of living with the threat of flooding from the North Sea.

Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Disaster pamphlets

Surviving reports of coastal flooding caused by a series of North Sea surges in 1570-71 describe dramatic inundations in the coastal counties of Norfolk, where “people were constrained to get up to the highest partes of the house”, and Cambridgeshire, where several “townes and villages were ouerflowed”. Meanwhile, the Lincolnshire village of Bourne, on the edge of the Fens, “was ouerflowed to [the] midway of the height of the church”.

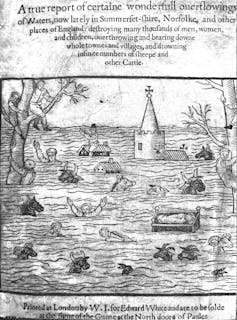

These colourful accounts of towns and churches under water were collected and printed in one of the first “disaster pamphlets” in London in 1571. It bore the lengthy title: A Declaration of Such Tempestious and Outragious Fluddes, as hath been in Diuers Places of England.

This pioneering form of news booklet rose to popularity in Shakespeare’s lifetime to cater for popular interest in the increasingly weird weather of those decades. Disaster pamphlets gathered nationwide news of floods, storms and lightning strikes into slim, pocket-sized booklets, printed in London under dramatic titles such as Feareful Newes of Thunder and Lightening (1606) and The Wonders of this Windie Winter (1613).

Of the London booksellers who sold these pamphlets and other “strange news” booklets, Shakespeare’s close contemporary, William Barley (1565-1614), was among the most prolific. Many pamphlets were accompanied by eye-catching illustrations of disaster scenes on their title pages and inside covers.

Natural disasters were by no means confined to the east coast. Two pamphlets – William Jones’s Gods Warning to his People of England, and the anonymous A True Report of Certaine Wonderfull Ouerflowings of Waters – reported on one of Britain’s worst natural disasters, the Bristol Channel flood of January 30 1607.

Cardiff University Special Collections, GW4 Treasures via Wikimedia

Their cover illustrations depicted scenes of suffering and survival, with submerged churches and steeples featuring prominently. Inside, writers knitted together statistics recording the number of miles of land flooded and cattle drowned with eyewitness accounts of local gentlemen and landowners, who described churches “hidden in the Waters”, the “tops of Churches and Steeples like to the tops of Rockes in the Sea”. Indeed, so high were the floodwaters, Jones wrote, that “some fled into the tops of Churches and Steeples to saue themselves”.

While newsbooks continued to grow in popularity, coming of age in the civil wars of the mid-1600s as a platform for reporting political news and views, disaster pamphlets focused specifically on storms and floods appear to have waned in popularity by the end of the 17th century. Their decline coincided with the rise in the later 1600s of the first local newspapers in England and Wales, which continued to feature news of floods and other weird weather events for centuries to come.

Nonetheless, references to disaster pamphlets lived on in poems such as Jean Ingelow’s High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire, 1571 – published in 1863 – which drew on the details of A Declaration to recreate the east coast floods of three centuries earlier from the point of view of a husband who loses his wife to the rising tide.

By focusing on the loss felt by one family, Ingelow draws attention to the human cost of these disasters which, then and now, can be buried beneath faceless figures of fatalities in news reports. The poem’s narrator notes that “manye more than mine and me” lost loved ones in that surge tide.

The concept of climate change was unknown to Shakespeare’s generation, yet the changing climate of the little ice age introduced anxieties into the reporting of weird weather in disaster pamphlets. Their authors would typically couch the causes of local floods as a national issue – as stirrings of divine anger at the sins of the English nation or of its Church.

Jones’s response to the Bristol Channel flood typified this approach. In Gods Warning, he describes the flood as a “watry punishment” – one of several “threatning Tokens of [God’s] heavy wrath extended towards us that had been experienced in recent years. How floods were represented in poems, pamphlets, newspapers and books have long reflected society’s wider anxieties over the question of what these weird, wild weather events might portend.

Lost communities

The English east coast possesses some of the fastest-eroding cliffs in Europe. In East Yorkshire, the Holderness cliffs from Bridlington to Spurn Point are eroding at an astonishing 1.8 metres per year. While erosion has been happening along this coastline since the end of the last (full) ice age approximately 11,700 years ago, it is today being accelerated by the rising seas and more frequent storms of climate change.

We can measure flooding or erosion in some very alarming numbers. According to the Flamborough Head to Gibraltar Point Shoreline Management Plan of 2010, the Holderness coast retreated by around two kilometres over the past thousand years. In the process, 26 villages named in the Domesday Book of 1086 disappeared under water.

Henry Gastineau

But literature goes further – revealing the experiences of those who lived on the edge of those crumbling clifftops, preserving fast-vanishing communities and coastlines for future generations.

In the early 20th century, histories of the Holderness coast’s lost villages were painstakingly pieced together from old photos, maps and archival records by Thomas Sheppard, whose Lost Towns of the Yorkshire Coast (1912) includes a map preserving the names and former locations of these shipwrecked villages: Cleton, Monkwell, Monkwike, Out Newton and Old Kilnsea, to name five. What must it have been like to live in these villages? How does their loss haunt today’s coastal communities, who are themselves facing a slow but sure retreat from the advancing sea?

Literature can provide what nature writer Helen MacDonald, in her collection of essays Vesper Flights (2020), calls the “qualitative texture” to enrich the statistics. It can reveal the ways of life and habits of thought of people who lived in these communities, and who adapted to the risks and benefits of living “on the edge”.

Juliet Blaxland’s The Easternmost House (2019) describes a year living in a “windblown house” in coastal Suffolk, “on the edge of an eroding clifftop at the easternmost end of a track that leads only into the sea”. The house – now demolished – was once Blaxland’s home. She wrote the book as “a memorial to this house and the lost village it represents, and to our ephemeral life here, so that something of it will remain once it has all gone”.

But Blaxland conjures more than bricks and mortar. She speaks to the mindset of coast-dwellers who pace out the distance between their houses and the advancing cliff edge, and who find solace, as well as sadness, in the inevitability of coastal loss. “Everyone has a cliff coming towards them, in the sense of our time being finite,” Blaxland writes. “The difference is that we can see ours, pegged out in front of us.”

From Noah to now

Coastal communities have learnt over centuries to live with uncertainty, and to continue their ways of life despite the risks. This “living with water” mentality shapes east coast communities just as surely as banks, barriers and rock armour shape the east coast’s cliffs, river mouths and beaches. It is in literature that we see this inner life revealed, and hear the voices of the past singing out to the present.

Singing was how we engaged young people with the past on the Noah to Now project. Across six months in 2024-25, colleagues from the University of Hull’s Energy and Environment Institute worked with singers, musicians and more than 200 young people in Hull and north-east Lincolnshire to rehearse and perform Benjamin Britten’s mid-20th century children’s opera, Noye’s Fludde, at Hull and Grimsby minsters.

The opera tells the biblical story of Noah in song, using the text of one surviving medieval flood play from 15th-century Chester as its libretto. Our chorus of school children performed as the animals in the ark, and were joined by other young people who took on solo roles or played in the orchestra.

Anete Sooda, University of Hull., CC BY-NC-SA

Rooted in the medieval past, the opera introduced participating schools to the lost flood play from medieval Hull, and to that play’s connections with the longstanding culture of living with water in the Humber region. One of our venues, Hull Minster, was the church in which Hull’s medieval mariners used to hang the ship (or ark) that they hauled through Hull’s streets every January, some 500 years ago.

Britten’s opera also resonates with more recent histories of east coast flooding. Noye’s Fludde was first performed in 1958 near the composer’s coastal home of Aldeburgh in Suffolk – a town devastated five years earlier by the disastrous North Sea flood of 1953.

Water swept into more than 300 houses in Aldeburgh shortly before midnight on January 31 1953 – forcing Britten to abandon 4 Crabbe Street, his seafront home. It was days before he could return to the house to write letters declaring that “we expect to feel less damp to-morrow”, and that “I think we’re going to try sleeping here to-night”. It was another week before Britten could report that “most of the mud’s gone now, thank God!”

The events of 1953 affected the whole Aldeburgh community, and the opportunity for the town to come together five years later to sing and perform an opera about flooding must have seemed especially poignant to all involved.

It was in the spirit of that first Aldeburgh performance that we involved other east coast communities in Hull and north-east Lincolnshire – each with their own long histories of flooding – in the staging of an opera that folds medieval and mid-20th century stories of flooding to address themes rooted in the past that are still relevant today.

Teachers from the participating schools spoke of their children’s enthusiasm for learning through the medium of stories and songs about a serious topic like flooding.

“[They were] so enthralled and so wanting to pass the message on of what they’d learnt,” a teacher from north-east Lincolnshire recalled about the children’s enthusiasm on returning from one of the workshops. “They came back just full of it – and full of the stories they’d been told as well.”

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

For you: more from our Insights series:

The post “From the Miller’s Tale to King Lear’s roaring sea, a history of flooding in literature” by Stewart Mottram, Professor of Literature and Environment, University of Hull was published on 12/04/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply