The world’s biggest election took place in heat so severe it claimed the lives of several poll workers.

Nearly one billion people were eligible to vote in the election that returned Narendra Modi to power in India, but many will have risked their health in doing so. India has just suffered the harshest heatwave of its history. For voters in the 64 countries with elections this year (comprising half of adults globally), the climate crisis is likely to loom large.

But, when all ballots are counted, will all that voting have made a difference?

This roundup of The Conversation’s climate coverage comes from our weekly climate action newsletter. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 30,000+ readers who’ve subscribed.

Let’s imagine a political response that is equal to the climate crisis. Joëlle Gergis, a climate scientist at the University of Queensland, explains what it would have to contend with.

The polls are melting

Like many of her colleagues, Gergis has been struck by how bleak the latest climate science assessments are.

“We need you to stare into the abyss with us and not turn away,” she says.

After decades of consciously inflaming the climate crisis – by continuing to burn more and more fossil fuel and destroying Earth’s natural carbon sponges, forests and wetlands – humanity has reached a stark juncture, she says:

“Even if nations make good on their net zero promises – which is a big ‘if’ because right now many nations’ pledges have no finance, weak implementation or limited political ambition, so are effectively empty promises – there is a 90% chance that we are still on track for 2.4°C of global warming under this best-case scenario, which will lock in centuries of irreversible changes to the climate system.”

For an idea of how bad this optimistic outcome is, consider that 1.5°C is the internationally agreed “safe” limit for long-term warming. Earth marked its first year-long breach of this temperature threshold in February.

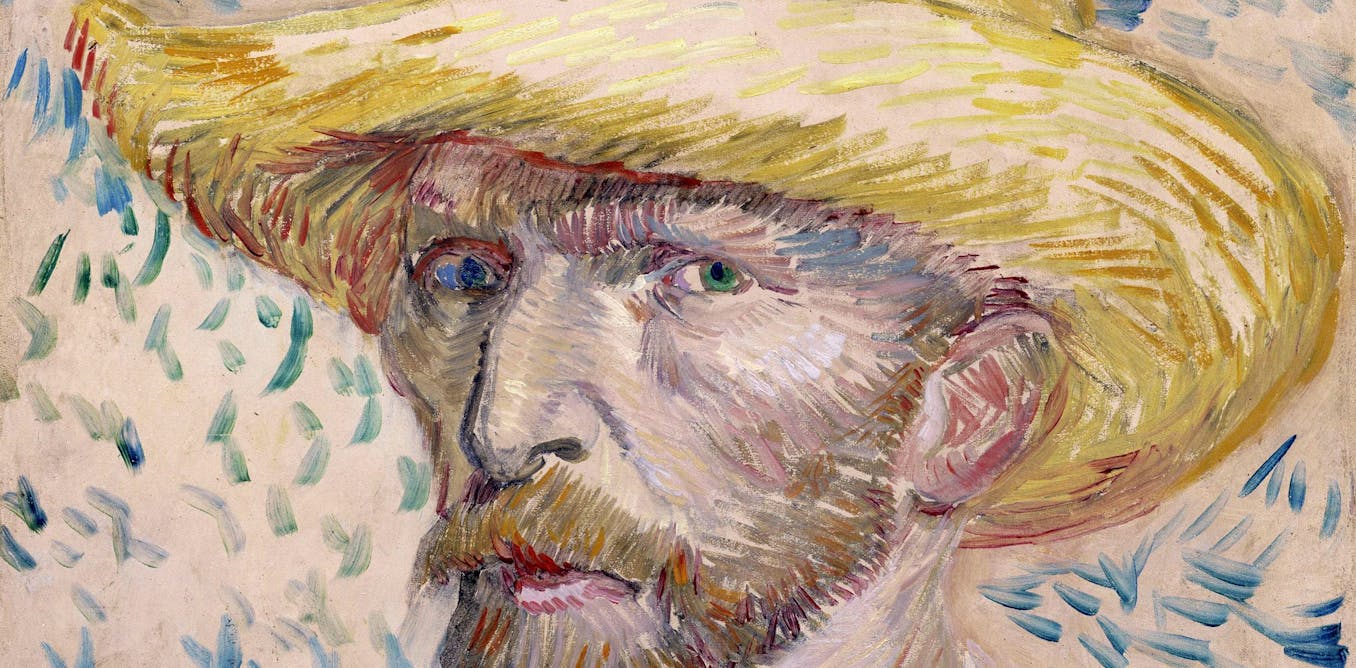

EPA-EFE/Rajat Gupta

Nature doesn’t get a vote and isn’t waiting for human institutions to provide relief writes Jonathan Goldenberg, an evolutionary biologist at Lund University.

Right now, North American migratory birds are evolving smaller bodies and longer wings to give themselves a slim advantage in increasingly brutal heatwaves. These adaptations, Goldenberg explains, make it easier for them to dissipate heat.

Read more:

How animals are changing to cope with stronger heatwaves

Reptiles and amphibians – so-called ectotherms, or cold-blooded animals (though their blood isn’t actually cold, Goldenberg says, they just rely on their environment to heat up and cool down rather than their metabolism like we do) – are less fortunate. Unable to directly regulate their internal temperature, lizards in central South Africa are responding to climate change in a way that may seem eerily familiar: by aiming to do as little as possible, and so avoid overheating.

“That probably means less time foraging and mating, potentially stunting their growth and reproduction,” Goldenberg says.

A potentially lethal inertia has gripped this species and our own. That’s not to say there aren’t regular votes on the outcome of Earth’s climate this century. There are, they just tend to be in boardrooms.

“Take the case of Shell, whose shareholders recently voted to decelerate the UK-based oil giant’s climate targets,” says Stefan Andreasson, a reader in comparative politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

“Shell had planned to cut its ‘net carbon intensity’ by 20% by 2030 and 45% by 2035, but now seeks a 15%-to-20% reduction by 2030 and no longer has a 2035 target.”

“One important explanation for [this shift] is that world demand for fossil fuels keeps rising”, Andreasson adds.

Who voted for this?

How is it that the profit expectations of businesses can supersede the public desire for a stable climate in a supposed democracy? It’s not by accident argues Eve Darian-Smith, a professor of global and international studies at the University of California, Irvine.

“Around the world, many countries are becoming less democratic. This backsliding on democracy and ‘creeping authoritarianism,’ as the US State Department puts it, is often supported by the same industries that are escalating climate change,” she says.

The notion of democratically elected leaders as protectors of the public’s interests, securing common goods like clean air and water, has been aggressively undermined in recent years. Darian-Smith traced the influence of campaign spending in her native US and found not only that the better-funded candidates tend to win, but that donations to Republican candidates from sources linked to the oil and gas industry have more than doubled since 2010.

Read more:

Rising authoritarianism and worsening climate change share a fossil-fueled secret

“The energy industry has in effect captured the democratic political process and prevented enactment of effective climate policies,” she says.

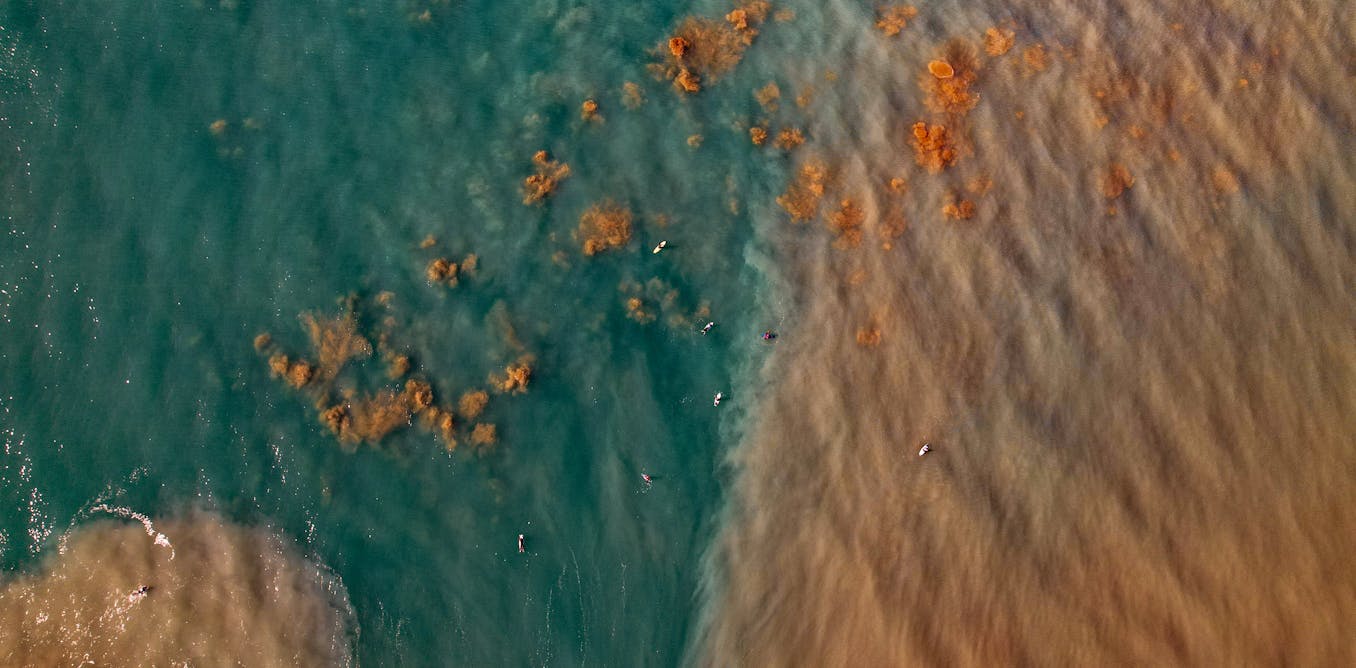

Huyangshu/Shutterstock

Is the lesson that we must suspend democracy to fix the climate? Quite the opposite according to Rebecca Willis, a professor in energy & climate governance at Lancaster University.

“To tackle the climate crisis, we need more, and better, democracy, not less,” she says.

Read more:

To tackle the climate crisis we need more democracy, not less

“The more we find out about how to build a public mandate for climate action, and the more we include people in genuine debate and deliberation, the more likely we are to find a way through the climate crisis.”

The post “Does voting help the climate?” by Jack Marley, Environment + Energy Editor, UK edition was published on 06/05/2024 by theconversation.com