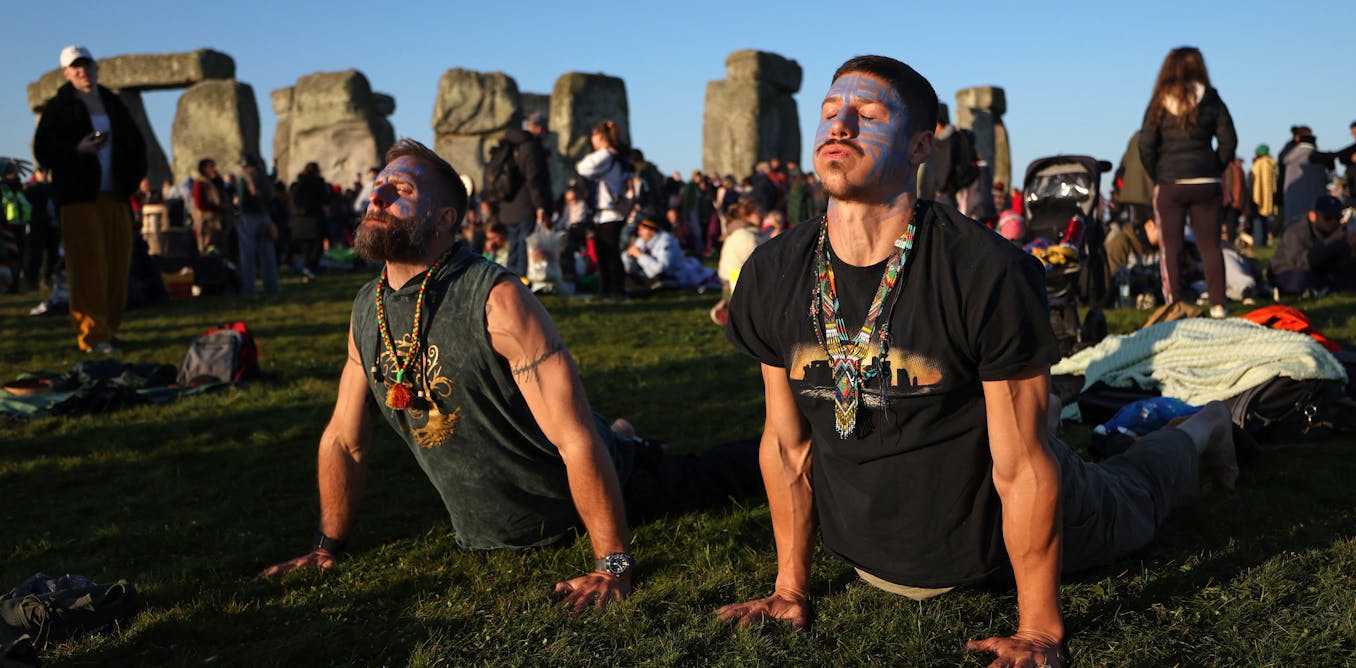

Climate activists Just Stop Oil launched a protest at Stonehenge, the 5,000-year-old stone monument in southern England, a day before thousands of people planned to gather there to celebrate the summer solstice.

Two members of the group sprayed three of the standing stones with an orange powder made from cornflour to draw attention to their campaign and its demands: that the UK government commit to ending the extraction and burning of oil, gas and coal by 2030.

Much like other protests by Just Stop Oil, which have included throwing paint – and sometimes tomato soup – at protected paintings in galleries, the Stonehenge action has been lambasted for threatening that which people hold dear: cultural heritage and national identity.

Politicians, archaeologists and heritage enthusiasts have condemned Just Stop Oil for supposedly endangering the stones. Some have even called for prison sentences – which could happen, as the Unesco World Heritage Site is protected by the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act (1979). Lichen species growing on the stones are also protected under the Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

The backlash demonstrates how heritage sites such as Stonehenge hold a sacred place for many and generate an almost desperate desire for rigid preservation. But Stonehenge and its landscape are dynamic features that forever shift and change. They have been beset by wars, roadworks and countless solstice gatherings. The stones were touched by thousands of hands before a barrier was installed and still bear the footfall of millions of visitors. They have withstood several interventions by archaeologists, who have hoisted the stones upright and replaced the lintels. In fact, all of the stones painted by Just Stop Oil – 21, 22 and 23 – have been re-erected or consolidated during the 20th century.

EPA-EFE/Andy Rain

This is also not the first time the stones have been vandalised. As well as graffiti carved into some of them, the stones have often been the stage for political protests. The slogan “ban the bomb”, referring to the call for nuclear disarmament, was sprayed across nine stones in 1961. The Stonehenge landscape will survive this protest by Just Stop Oil.

The real threat to Stonehenge

What Stonehenge may not withstand is climate change. The UK is set to experience warmer, wetter winters and hotter, drier summers, as well as an increase in the occurrence and severity of extreme weather which will include high winds and flooding. This will have an impact on the stones and their landscape, exacerbating erosion of the faces of the stones caused by freezing and thawing while much wetter or much drier soil undermines their stability.

There are 70 species of lichen growing on the stones, some of which are rare for the surrounding Salisbury plain. But drier summers brought about by climate change may deteriorate the environment required for these species to thrive.

While Just Stop Oil’s protest at Stonehenge has generated outrage, there is silence over the cumulative and ongoing effects of climate change upon this and other heritage sites. There is little to no public uproar about climate change posing one of the biggest challenges to cultural landscapes, buried archaeology and the built environment. Without immediate and drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, we will witness the loss and change of beloved heritage sites which will in turn affect our economy, way of life and sense of place.

Junk Culture/Shutterstock

Beneath it all, a fear of loss

Heritage and climate change have a complex relationship. Climate change affects, and will continue to affect, heritage – but the reverse is also true. Heritage can encourage climate action. My research has demonstrated that greater awareness of heritage loss can raise consciousness of the climate crisis and prompt action.

This is in part due to the emotional attachment people have to local and national heritage sites, and even those in other countries. When climate change and heritage meet during these protests, it is incredibly emotive. The visceral response to the protest at Stonehenge reveals our fear of loss and change, but this can act as a catalyst for climate action too. Just Stop Oil’s protest appears to have highlighted a collective fear of losing revered heritage, yet the conversation about it has overlooked the main instigator.

The orange cornflour has been washed away by the charity English Heritage, which reports no visible damage. But climate change will continue to threaten Stonehenge, its wider landscape and the rare lichen living on the stones. We must channel our concern over potential damage to Stonehenge towards the real threats facing heritage sites.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 30,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

The post “if you worry about damage to British heritage you should listen to Just Stop Oil” by Sarah Kerr, Lecturer in Archaeology and Radical Humanities, University College Cork was published on 06/21/2024 by theconversation.com