Numerous images exploring the blurry, textured thickness of light feature prominently in Making Waves; Breaking Ground, a group exhibition at the Bowhouse in St Monans, Fife. It is an apt theme for this coastal corner of Scotland, where, at this time of year, shadows are soft and the days frequently take on a dense, milky quality.

The exhibition is the initiative of curators Sophie Camu and Alexander Lindsay, who have collaborated with the Purdy Hicks Gallery in London to bring together the works of 11 contemporary Scottish and international artists. Spanning painting, photography and film, these often ethereal works explore the “natural environments of our modern world”.

Susan Derges

Susan Derges’ image Full Moon Spawn from 2007 becomes increasingly absorbing the more attention you devote to it. On the surface, it is a depiction of the full moon. But, contrary to expectations, it is not surrounded by scudding clouds. Instead, it is framed by strange, jellied clumps and waterborne detritus.

This is an image, we gradually come to realise, that suggests a viewpoint from somewhere below the surface of the water, as though this were a trout’s-eye view of the night sky, and as if our atmosphere were not air, but a body of fresh water, teaming with frog spawn.

Derges came to prominence in the 1990s for her photograms of the River Taw close to her Devon home, which she created without the use of a camera. At night, she would submerge photographic paper within the flowing water, and would use the rippled, reflected light of the moon to leave its imprint on the immersed sheet.

To create Full Moon Spawn, Derges contrived a more elaborate setup in her studio. But it is nonetheless a continuation of a theme she has pursued ever since, which we might call her aqueous perspective: her fascination with the shape-shifting look of things through a liquid medium. For her, photography is a watery business.

Samantha Clark

Haar – the name used up and down Scotland and England’s east coast for the clammy sea fog that billows noiselessly inland from the sea – is the title of one of Samantha Clark’s large acrylic paintings. Painted in 2024 in Orkney, where she now lives, it depicts a thick, vaporous field, the image built up from a complex overlapping mesh of laboriously drawn lines.

Other works bear names such as This Salted Light, Submerge, or Salt Fog Light. The omnipresence of water is her guiding theme. For Clark, it is the interconnecting life-giving tissue that flows through both us and the land.

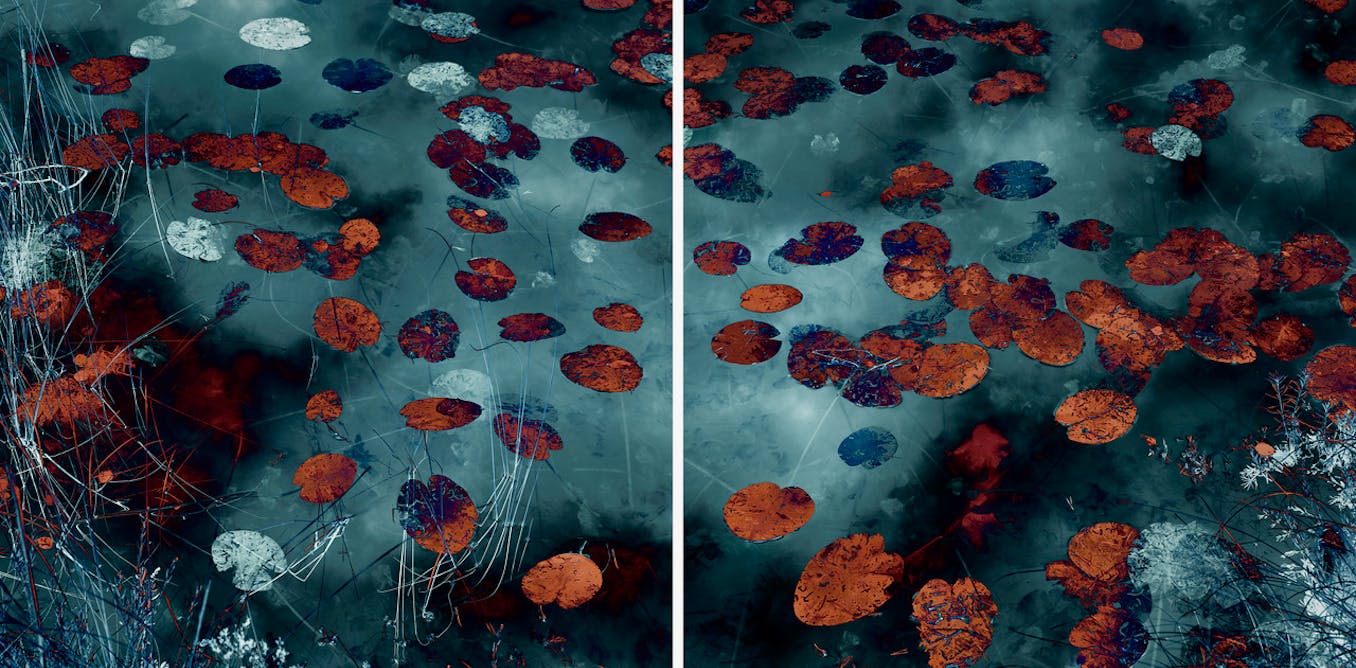

Among the other artists included are three Finnish photographers: Santeri Tuori, Jorma Puranen and Sandra Kantanen. In separate ways, both Kantanen and Tuori revisit the painterly theme that so preoccupied Claude Monet in his later years: the unsteadiness of light on foliage floating on the still surface of a pond.

Jorma Puranen

Puranen is equally captivated by scattered, refracted light. In his images, and especially in his series, Icy Prospects, he maintains a fruitful ambiguity about the substantiality of the things he depicts. A frozen surface, for instance, thick with bubbles, mirrors a winter’s sky in a way that makes it appear wet and watery.

Camu and Lindsay present the works in this exhibition as upending the traditional concepts of landscape art. It is a bold claim, especially given that many of the artists are demonstrably familiar with this tradition (Samantha Clark, for instance, has written in detail of her interest in the watercolours of William Turner in her poignant memoir The Clearing).

But it also seems right to infer that few of the artists in this exhibition would identify with the values that the landscape genre has all too often embraced. So often the western landscape tradition has served as the preferred visual form for expressing possession of the land of others.

Kathrin Linkersdorff

The artists in Making Waves; Breaking Ground share a commitment to pursuing a more compassionate way of looking and being in a place. They practise modes of attentiveness that do not reduce their surroundings to an easy-to-access spectacle, but acknowledge a physical interconnectedness with the world around them.

What links the works in this exhibition is a noticeable absence of horizon lines. Instead, the artists immerse themselves in an atmosphere, or enter a world filled with things which seem to loom up unpredictably. This approach reflects a refusal to prioritise between the infinitesimally small and cosmic immensity.

Most importantly, they don’t see themselves as separate from the worlds they depict. Our seeing eyes, they suggest, are made of the same physical substances as the things they see.

Making Waves Breaking Ground runs until August 31, at the Bowhouse, St Monans, Fife, free

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The post “a luminous show that reveals the interconnectedness of nature” by Alistair Rider, Senior Lecturer in Art History, University of St Andrews was published on 08/20/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply