Earlier this year, a group of researchers published a paper on the remarkable phenomenon of sex reversal in several Australian birds, including wild magpies and kookaburras.

They’ve yet to discover the exact mechanism through which this happens. Nonetheless, their discovery would have fascinated medieval scientists, who were just as engaged in trying to understand sex and gender in the avian world.

Medieval ideas of bird ‘sex’

Sexual differences in birds include anatomical and behavioural characteristics that vary within and across species.

Scientists have found biological triggers for sex-specific traits that may shift during an individual’s lifetime. For example, female ducks and chickens can take on “masculine” attributes once their egg-laying years are over.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE) observed similar changes in birds almost 2,400 years ago. His text History of Animals explained that the physical characteristics of sex in chickens and other animals could change according to action and circumstance.

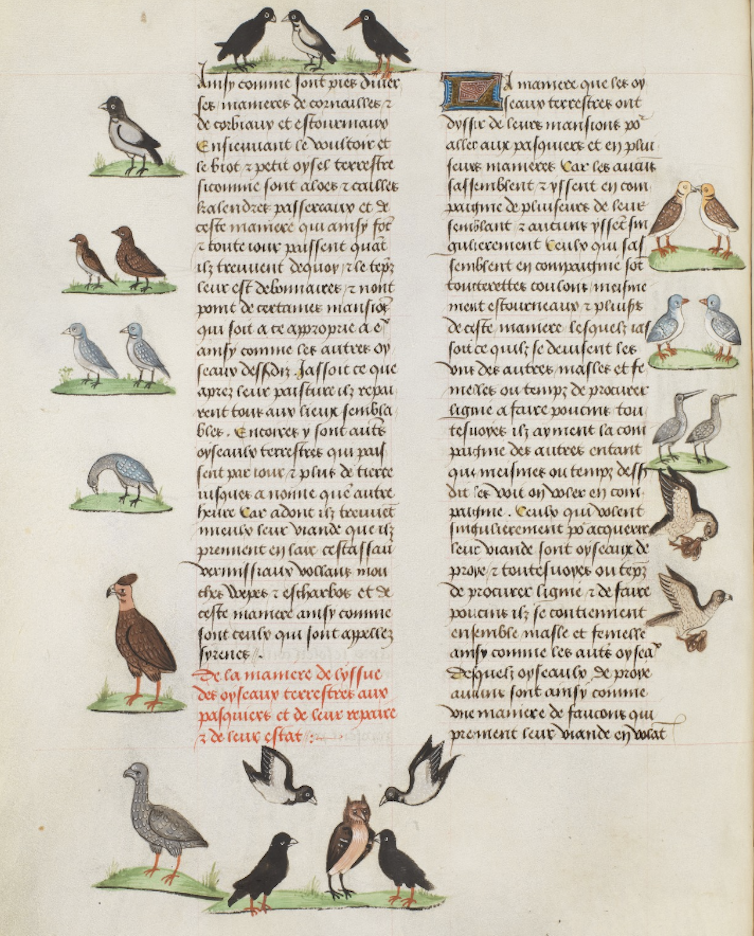

Bibliothèques d’Amiens Métropole, MS 399, fols. 144v-145r.

In medieval Europe, the word “sexus” was used to refer to everything people now label as “sex”, “gender” and “sexuality”.

Research on sexus occurred in all the places of medieval science: schools, universities, monasteries, households, workshops and natural landscapes. Medieval people developed their own experiments and theories based on their lived experiences.

Those who read Latin or Greek studied and revised the findings of ancient authorities such as Aristotle, Galen and Pliny the Elder.

Cultural exchange also helped advance scientific knowledge. The 11th-century physician-monk Constantine the African was one of many who translated Arabic texts for readers of Latin.

Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 1462, fols. 60v–61r, CC BY-NC

Why did medieval scientists research sexus?

Some medieval people wanted to learn about sex and procreation in animals to try to improve their own health.

For instance, Hildegard of Bingen (circa 1098–1179) wrote about sex-specific behaviours and uses of birds in her medical treatise Physica.

She claimed ointments made from the fat of a sparrowhawk mixed with botanical ingredients could inhibit sexual arousal. Until this has been tested, we will remain sceptical (although other strange medieval medicines have proven surprisingly effective).

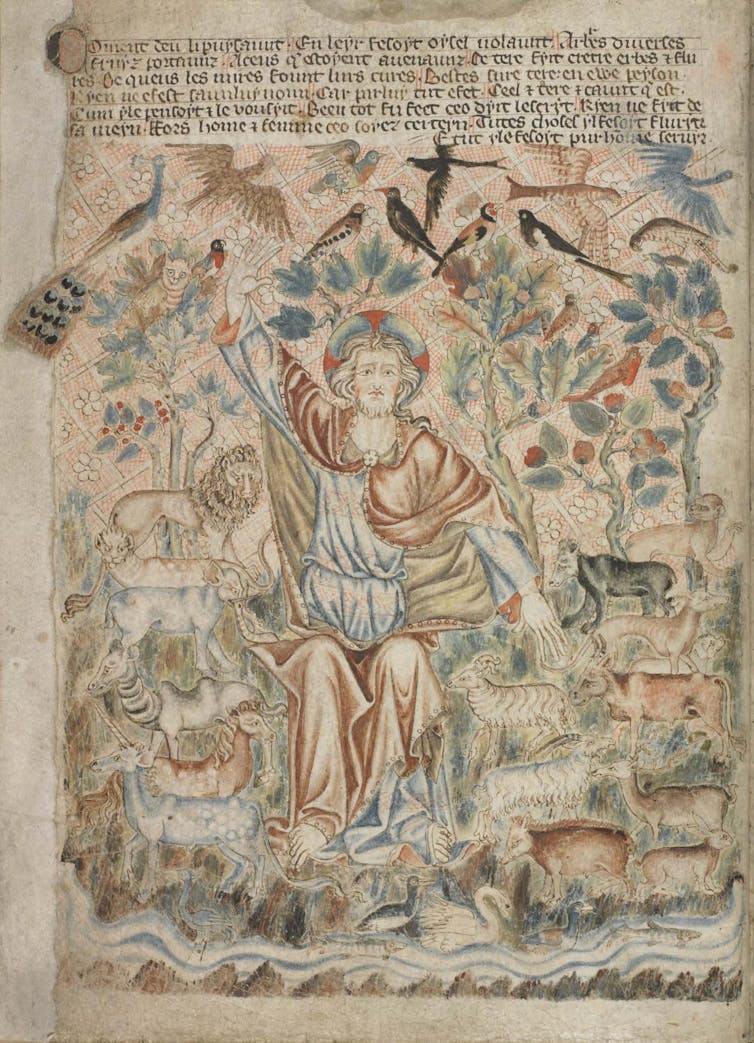

British Library, Additional MS 47682, fol. 2v

The findings of Frederick II

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (1194–1250) was a passionate falconer, which means he trained birds of prey to hunt wild animals. He studied all kinds of birds and developed evidence based theories about them. He even owned an Australasian cockatoo.

Frederick wrote a treatise, The Art of Hunting with Birds, based on decades of his work and research. In it, he observed that sexual behaviours and reproduction differed between species of birds. Similarly, scientists today use reproductive isolation to classify different species.

British Library, Yates Thompson MS 13, fol. 73r

Some of Frederick’s ideas are outdated, such as his explanation for why female raptors grow larger than males. His theory was based on “humoralism” – an ancient system of medicine in which four bodily fluids (blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile) were thought to correspond to four qualities (dry, hot, cold and moist), and that all of these influenced animal physiology, including sexus.

Modern scientists think females may grow larger because this allows them to better defend their nest – but this is still being questioned.

Bibliothèque de Genève, MS fr. 170, fol. 27v, CC BY-NC

Many of Frederick’s findings align with current knowledge about bird anatomy, pair-bonding, migration, sexual reproduction and the rearing of offspring. For example, after observing that parrots have thick tongues, he deduced this is what allows them to imitate human voices. Today’s scientists agree.

The term “cuckold” can also be traced back to medieval understandings of cuckoos, which sneak their eggs into other birds’ nests to be raised.

Frederick II verified this behaviour himself. He carefully fed an unfamiliar nestling until he could identify it as a young cuckoo. The cuckoo’s cross-species brood parasitism continues to be studied by researchers today.

Spotting variable behaviours

Birds in medieval times were often associated with unconventional sexual behaviours.

Bestiaries (collections of moralised information about animals) claimed female vultures could conceive without males. This is called “parthenogenesis” and it does happen – although it’s rare.

Some bestiaries claimed female partridges were impregnated via scent. Although this isn’t backed by modern science, partridges and other land fowls are now known for their variable breeding strategies.

For example, some females lay eggs in two nests so one can be incubated by the male. This behaviour, known as double-nesting, was also observed by Aristotle.

Bestiaries also reported same-sex pairings in various bird species – something modern researchers have likewise observed.

Scientific scrutiny

Like today, theories back then were disputed and tested. The barnacle goose was once said to grow on wood at sea rather than hatching from eggs. It’s possible people who saw goose barnacles thought they were the early forms of a barnacle goose.

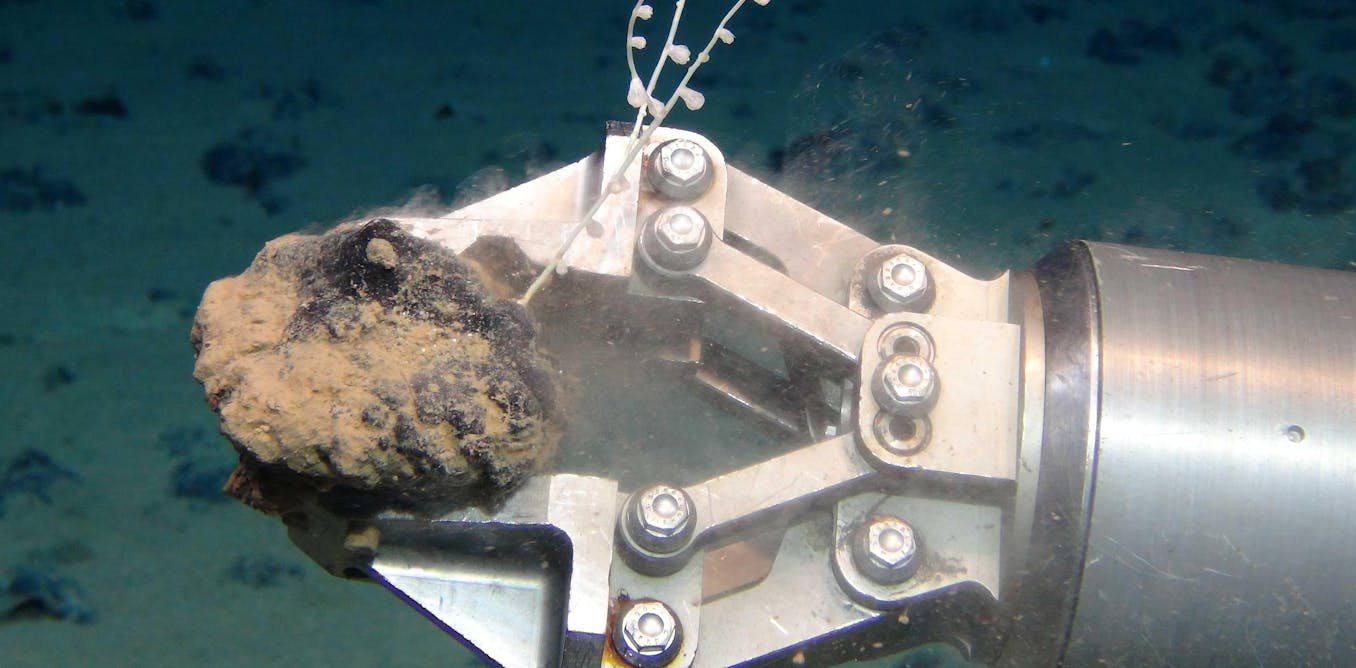

In search of proof, Frederick sent expeditions to bring specimens of timber for observation, finding no evidence of avian bodies.

British Library, Harley MS 4751, fol. 36

The philosopher Albert the Great called the theory “entirely absurd” in his 13th-century text On Animals. Nonetheless, the legend endured into the 17th century and is referenced in William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest.

Modern scientists don’t yet know what causes sex reversal in native Australian birds. But the recent findings, along with the history of medieval science, remind us how ideas of “nature” and “sex” have always been tested and revised.

The post “Bird sex fascinated medieval thinkers as much as people today” by Clare Davidson, Research Fellow, Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Catholic University was published on 11/26/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply