This November, Bob Dylan performed the final concerts of his Rough and Rowdy Ways tour at the Royal Albert Hall in London. The tour picked up where Dylan left off just before the COVID pandemic – endlessly on the road since 1988. But now at the age of 83, the concerts might well be Dylan’s last.

The Rough and Rowdy Ways tour was billed as running from 2021 to 2024, but at the time of publication, there seem to be no future tour dates on the horizon. As Dylan himself wondered on his most recent album: How much longer can it last? How long can this go on?

Dylan has diced with death more than once – think of his infamous motorcycle crash in 1966, or his serious heart ailment in 1997 – and death has preoccupied his songs increasingly in recent years. Throughout this tour, Dylan’s thoughts have been heavily focused on his own mortality and his own legacy.

If the Albert Hall concerts this year are to be his last on the road, then it’s a fitting venue at which to bow out, having first played it nearly 60 years ago. Back then, Dylan was a restless, hungry artist, reinventing his sound, his image, his voice with every album – sometimes, within months of release.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

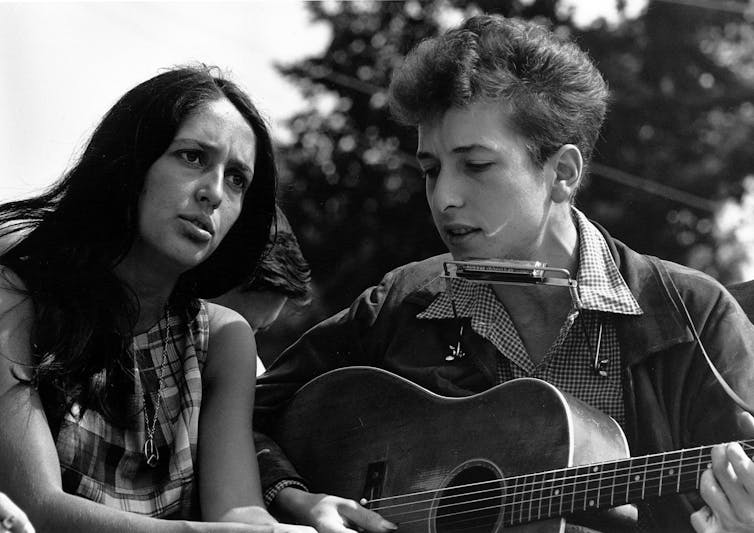

Between 1962 and 1966, Dylan went from being a Midwest folk singer to the voice of his generation beatnik, via civil rights firebrand, rewriting the popular music songbook as he went.

With each successive regeneration, he seemed determined not only to redefine rock and popular music, but to alienate his audience in the process as well. He was an artist in search of answers, who didn’t give those in his wake time to catch their breath. Sixty years on, and now well into his ninth decade, things haven’t changed.

His own version

Dylan’s final night at the Albert Hall was a summation of how he remains a defiant artist still forging new ideas. The performance contained highlights from his entire career. Eight of the 17 songs were written and released before the 1990s, while everything else was from the 2020 album after which the tour is named. But each song was radically reinvented, reworked to Dylan’s ever-changing vision, with some of the songs even being rearranged during his three-day residency at the Albert Hall.

Take My Own Version of You (2020), Dylan’s late masterpiece about the process of creation. In the song, the narrator – a modern-day Prometheus, maybe even Dylan himself – tells of his efforts to construct his vision from “limbs and livers and brains and hearts”.

Raph_PH/Wiki Commons, CC BY-SA

The song’s arrangement at the start of the Rough and Rowdy Ways tour was as a brooding, Tex-Mex noir. But by the tour’s end, Dylan had stripped his ode to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to its essentials, until all that was left by the final Royal Albert Hall concert was Dylan’s voice.

He rapped the lyrics, accompanied by his own sparse piano backing and the occasional guitar flourish. It was a performance that evoked similarities to Dylan’s rapid-style solo delivery of songs like It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) (1965) on the same stage in the 1960s.

My Own Version of You is a song in which Dylan reflects on his own artistic and creative processes. And in its radical and stark new arrangement in this final concert, Dylan was returning to how he started: as an artist whose main tools have always been his voice and his words. It’s the reason he was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 2016, after all.

Read more:

Bob Dylan’s Nobel prize – and what really defines literature

It’s perhaps unsurprising then that the entire concert was a reflection on the process of creation. Dylan’s process is to reshape, disassemble, reassemble and strip back. While the process is undoubtedly frustrating for some in the audience, as they struggle to guess what song Dylan is performing, it is also exhilarating to watch an artist reinventing himself and his songs in real time.

They become assemblages of the old and the new, the found and the borrowed. When I Paint My Masterpiece (1971) is no longer an elegiac sing-along song, but instead a reggae-influenced tune via Dylan’s own down-and-dirty blues of the Time Out of Mind album (1997), with a bit of his born-again gospel thrown in for good measure.

National Archives at College Park

All Along the Watchtower (1968) is no longer Dylan’s homage to Jimi Hendrix’s career-defining cover version, but a fable of hell trapped on a loop from which the narrator seeks escape, with echoes of T.V. Talkin’ Song (1990). And Every Grain of Sand (1981) becomes a melancholic requiem by an old man with no regrets, determined to rage against time. It conjures memories of Dylan’s version of Tangled Up In Blue, performed at the Royal Albert Hall in 2013.

If this was to be Dylan’s last ever live performance, then what does it say about him and his place in music history? Well, that he remains as vital an artist as he was in the 1960s, one who continues to reinvent himself, who continues to chase that restless, hungry feeling and who doesn’t look back, but constantly forward.

Dylan would leave behind an expansive body of work – both studio albums and live recordings – for scholars, critics and audiences alike to rediscover for decades, if not centuries to come. And in that rediscovery, they will learn much about what it means to be an artist.

The post “Bob Dylan just finished what could be his last tour – but remains a defiant artist forging new ideas” by James Fenwick, Senior Lecturer in Creative and Cultural Industries, University of Manchester was published on 11/19/2024 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply