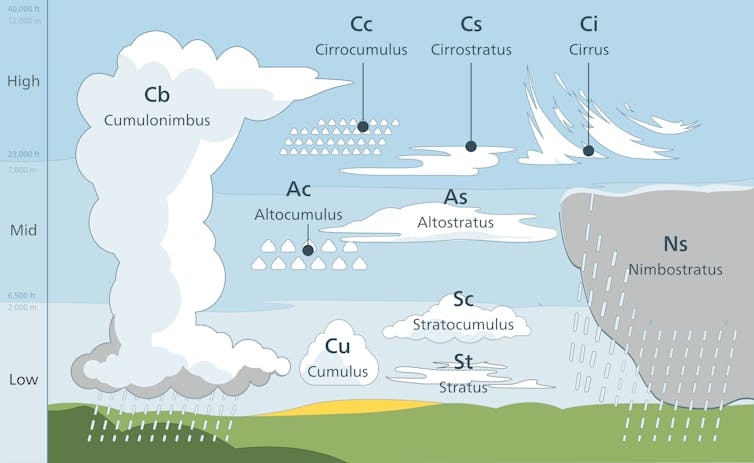

As a scholar researching clouds, I have spent much of my time trying to understand the economy of the sky. Not the weather reports showing scudding rainclouds, but the deeper logic of cloud movements, their distributions and densities and the way they intervene in light, regulate temperatures and choreograph heat flows across our restless planet.

Recently, I have been noticing something strange: skies that feel hollowed out, clouds that look like they have lost their conviction. I think of them as ghost clouds. Not quite absent, but not fully there. These wispy formations drift unmoored from the systems that once gave them coherence. Too thin to reflect sunlight, too fragmented to produce rain, too sluggish to stir up wind, they give the illusion of a cloud without its function.

We think of clouds as insubstantial. But they matter far beyond their weight or tangibility. In dry Western Australia where I live, rain-bringing clouds are eagerly anticipated. But the winter storms which bring most rain to the south-west are being pushed south, depositing vital fresh water into the oceans. More and more days pass under a hard, endless blue – beautiful, but also brutal in its vacancy.

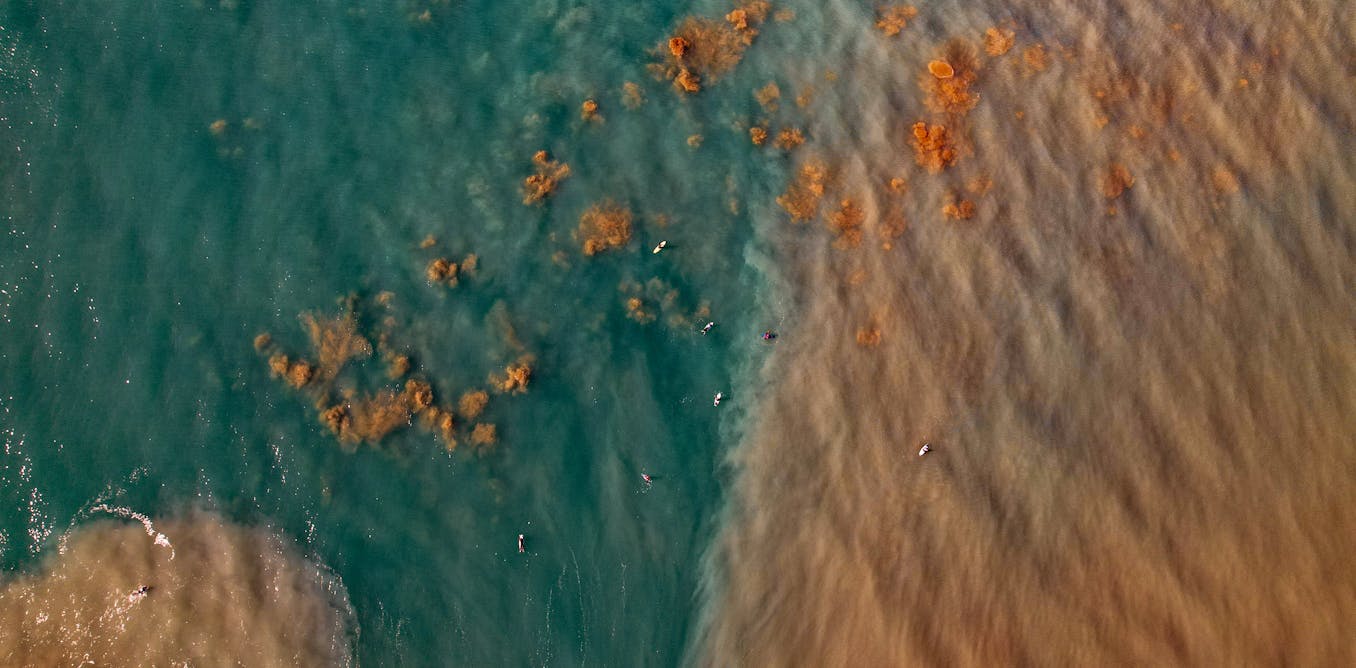

Worldwide, cloud patterns are now changing in concerning ways. Scientists have found the expanse of Earth’s highly reflective clouds is steadily shrinking. With less heat reflected, the Earth is now trapping more heat than expected.

A quiet crisis above

When there are fewer and fewer clouds, it doesn’t make headlines as floods or fires do. Their absence is quiet, cumulative and very worrying.

To be clear, clouds aren’t going to disappear. They may increase in some areas. But the belts of shiny white clouds we need most are declining between 1.5 and 3% per decade.

These clouds are the best at reflecting sunlight back to space, especially in the sunniest parts of the world close to the equator. By contrast, broken grey clouds reflect less heat, while less light hits polar regions, giving polar clouds less to reflect.

Clouds are often thought of as an ambient backdrop to climate action. But we’re now learning this is a fundamental oversight. Clouds aren’t décor – they’re dynamic, distributed and deeply consequential infrastructure able to cool the planet and shape the rainfall patterns seeding life below. These masses of tiny water droplets or ice crystals represent climate protection accessible to all, regardless of nation, wealth or politics.

On average, clouds cover two-thirds of the Earth’s surface, clustering over the oceans. Of all solar radiation reflected back to space, clouds are responsible for about 70%.

Clouds mediate extremes, soften sunlight, ferry moisture and form invisible feedback loops sustaining a stable climate.

Bernd Dittrich/Unsplash, CC BY-NC-ND

When loss is invisible

If clouds become rarer or leave, it’s not just a loss to the climate system. It’s a loss to how we perceive the world.

When glaciers melt, species die out or coral reefs bleach and die, traces are often left of what was there. But if cloud cover diminishes, it leaves only an emptiness that’s hard to name and harder still to grieve. We have had to learn how to grieve other environmental losses. But we do not yet have a way to mourn the way skies used to be.

And yet we must. To confront loss on this scale, we must allow ourselves to mourn – not out of despair, but out of clarity. Grieving the atmosphere as it used to be is not weakness. It is planetary attention, a necessary pause that opens space for care and creative reimagination of how we live with – and within – the sky.

NASA, CC BY-NC-ND

Reading the clouds

For generations, Australia’s First Nations have read the clouds and sky, interpreting their forms to guide seasonal activities. The Emu in the Sky (Gugurmin in Wiradjuri) can be seen in the Milky Way’s dark dust. When the emu figure is high in the night sky, it’s the right time to gather emu eggs.

The skies are changing faster than our systems of understanding can keep up.

One solution is to reframe how we perceive weather phenomena such as clouds. As researchers in Japan have observed, weather is a type of public good – a “weather commons”. If we see clouds not as leftovers from an unchanging past, but as invitations to imagine new futures for our planet, we might begin to learn how to live more wisely and attentively with the sky.

This might mean teaching people how to read the clouds again – to notice their presence, their changes, their disappearances. We can learn to distinguish between clouds which cool and those which drift, decorative but functionally inert. Our natural affinity to clouds makes them ideal for engaging citizens.

To read clouds is to understand where they formed, what they carry and whether they might return tomorrow. From the ground, we can see whether clouds have begun a slow retreat from the places that need them most.

Valentin de Bruyn/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-ND

Weather doesn’t just happen

For millennia, humans have treated weather as something beyond our control, something that happens to us. But our effects on Earth have ballooned to the point that we are now helping shape the weather, whether by removing forests which can produce much of their own rain or by funnelling billions of tonnes of fossil carbon into the atmosphere. What we do below shapes what happens above.

We are living through a very brief window in which every change will have very long term consequences. If emissions continue apace, the extra heating will last millennia.

I propose cloud literacy not as solution, but as a way to urgently draw our attention to the very real change happening around us.

We must move from reaction to atmospheric co-design – not as technical fix, but as a civic, collective and imaginative responsibility.

Professor Christian Jakob provided feedback and contributed to this article, while Dr Jo Pollitt and Professor Helena Grehan offered comments and edits.

The post “Clouds are vital to life – but many are becoming wispy ghosts. Here’s how to see the changes above us” by Rumen Rachev, PhD Candidate, Edith Cowan University was published on 12/29/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply