Red skies in August, longer fire seasons and checking air quality before taking my toddler to the park. This has become the new norm in the western United States as wildfires become more frequent, larger and more catastrophic.

As an ecologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, I know that fires are part of the natural processes that forests need to stay healthy. But the combined effects of a warmer and drier climate, more people living in fire-prone areas and vegetation and debris built up over years of fire suppression are leading to more severe fires that spread faster. And that’s putting humans, ecosystems and economies at risk.

To help prevent catastrophic fires, the U.S. Forest Service issued a 10-year strategy in 2022 that includes scaling up the use of controlled burns and other techniques to remove excess plant growth and dry, dead materials that fuel wildfires.

However, the Forest Service’s wildfire management activities have been thrown into turmoil in 2025 with funding cuts and disruptions and uncertainty from the federal government.

The planet just saw its hottest year on record. If spring and summer 2025 are also dry and hot, conditions could be prime for severe fires again.

More severe fires harm forest recovery and people

Today’s severe wildfires have been pushing societies, emergency response systems and forests beyond what they have evolved to handle.

Extreme fires have burned into cities, including destroying thousands of homes in the Los Angeles area in 2025 and near Boulder, Colorado, in 2021. They threaten downstream public drinking water by increasing sediments and contaminants in water supplies, as well as infrastructure, air quality and rural economies. They also increase the risk of flooding and mudslides from soil erosion. And they undermine efforts to mitigate climate change by releasing carbon stored in these ecosystems.

In some cases, fires burned so hot and deep into the soil that the forests are not growing back.

While many species are adapted to survive low-level fires, severe blazes can damage the seeds and cones needed for forests to regrow. My team has seen this trend outside of Fort Collins, Colorado, where four years after the Cameron Peak fire, forests have still not come back the way ecologists would expect them to under past, less severe fires. Returning to a strategy of fire suppression − or trying to “go toe-to-toe with every fire” − will make these cases more common.

Bella Oleksy/University of Colorado

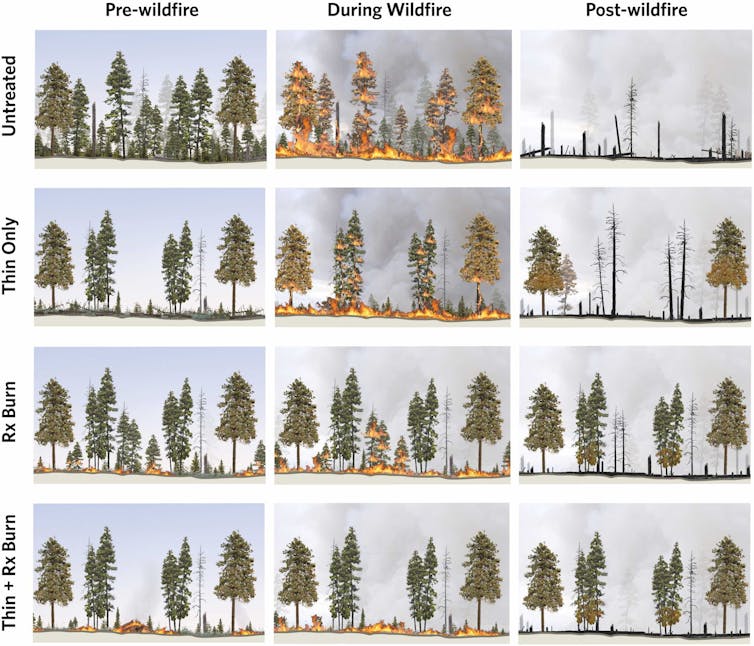

Proactive wildfire management can help reduce the risk to forests and property.

Measures such as prescribed burns have proven to be effective for maintaining healthy forests and reducing the severity of subsequent wildfires. A recent review found that selective thinning followed by prescribed fire reduced subsequent fire severity by 72% on average, and prescribed fire on its own reduced severity by 62%.

Kimberley T. Davis, et al., Forest Ecology and Management, 2024, CC BY

But managing forests well requires knowing how forests are changing, where trees are dying and where undergrowth has built up and increased fire hazards. And, for federal lands, these are some of the jobs that are being targeted by the Trump administration.

Some of the Forest Service staff who were fired or put in limbo by the Trump administration are those who do research or collect and communicate critical data about forests and fire risk. Other fired staff provided support so crews could clear flammable debris and carry out fuel treatments such as prescribed burns, thinning forests and building fire breaks.

Losing people in these roles is like firing all primary care doctors and leaving only EMTs. Both are clearly needed. As many people know from emergency room bills, preventing emergencies is less costly than dealing with the damage later.

Logging is not a long-term fire solution

The Trump administration cited “wildfire risk reduction” when it issued an emergency order to increase logging in national forests by 25%.

But private − unregulated − forest management looks a lot different than managing forests to prevent destructive fires.

Logging, depending on the practice, can involve clear-cutting trees and other techniques that compromise soils. Exposing a forest’s soils and dead vegetation to more sunlight also dries them out, which can increase fire risk in the near term.

AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez

In general, logging that focuses on extracting the highest-value trees leaves thinner trees that are more vulnerable to fires. A study in the Pacific Northwest found that replanting logged land with the same age and size of trees can lead to more severe fires in the future.

Research and data are essential

For many people in the western U.S., these risks hit close to home.

I’ve seen neighborhoods burn and friends and family displaced, and I have contended with regular air quality warnings and red flag days signaling a high fire risk. I’ve also seen beloved landscapes, such as those on Cameron Peak, transform when conifers that once made up the forest have not regrown.

Bella Oleksy/University of Colorado

My scientific research group and collaborations with other scientists have been helping to identify cost-effective solutions. That includes which fuel-treatment methods are most effective, which types of forests and conditions they work best in and how often they are needed. We’re also planning research projects to better understand which forests are at greatest risk of not recovering after fires.

This sort of research is what robust, cost-effective land management is based on.

When careful, evidence-based forest management is replaced with a heavy emphasis on suppressing every fire or clear-cutting forests, I worry that human lives, property and economies, as well as the natural legacy of public lands left to every American, are at risk.

The post “Controlled burns reduce wildfire risk, but they require trained staff and funding − this could be a rough year” by Laura Dee, Associate Professor of Ecology, University of Colorado Boulder was published on 04/23/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply