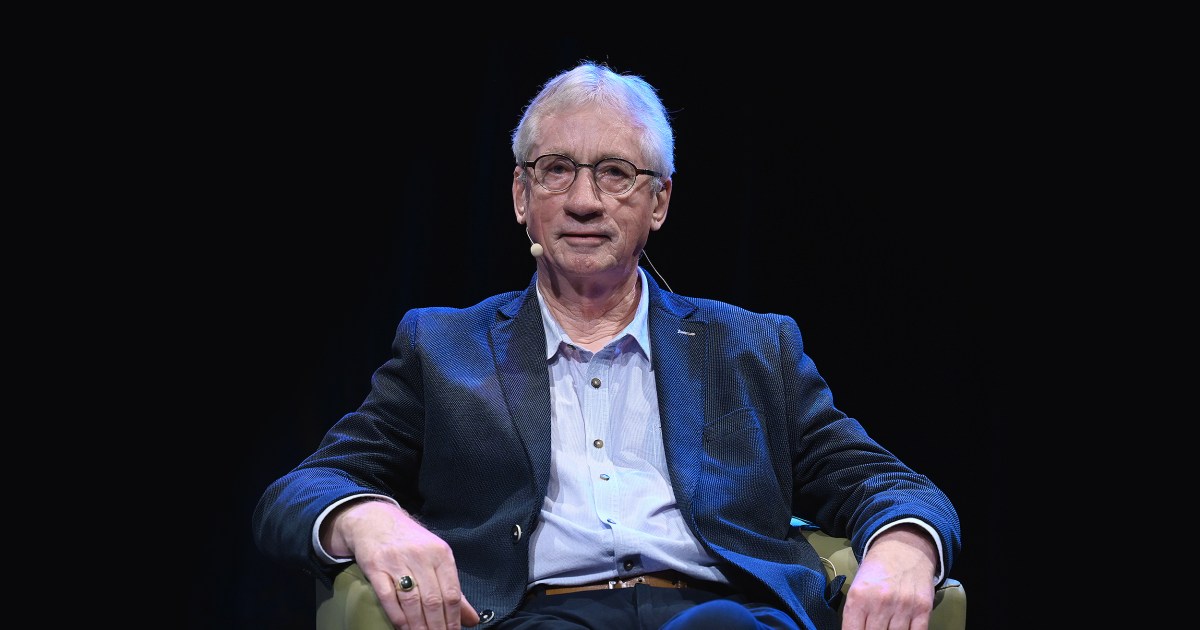

Primatologist Frans de Waal, who studied the emotional and psychological similarities between humans and apes, died on March 14, 2024. He passed from stomach cancer at his home in Stone Mountain, Ga., and is survived by his wife of 40 years, Catherine Marin, and his brothers. He was 75 years old.

“It’s difficult to sum up the enormity of [his] impact,” Lynne Nygaard, chair of the department of psychology at Emory University, said in the school’s tribute to his life and career. “He was an extraordinarily deep thinker who could also think broadly, making insights that cut across disciplines.”

“Frans” was born Franciscus Bernardus Maria de Waal in 1948. He trained as a zoologist and ethologist in his native Netherlands and received his PhD in biology from the University of Utrecht in 1977.

His first major contribution to primatology came at the beginning of his career. Over a six-year project, he studied how chimpanzees reconciled after fights and showed they engaged in activities such as embracing, giving peace offerings, and grooming each other. The project proved a milestone in primate cognition studies.

It was also the first time a researcher used terminology like “reconcile” to describe prosocial behaviors in animals. Before de Waal, the Emory tribute notes, researchers leaned on less humanizing, more stringent academese to discuss animal behaviors — for instance, “post-fight, affiliative contact” instead of “embrace.”

Over his career, de Waal would publish hundreds of scientific articles comparing human behaviors with those displayed by their close evolutionary kin. He found evidence to show apes could cooperate, feel emotions, act altruistically, resolve conflicts, pass down knowledge, and build meaningful relationships much like humans.

“There are no uniquely human emotions. All emotions that we have, we share with other species. They may be a bit more sophisticated or elaborate in our species, but we share all of them,” de Waal told Big Think.

He argued similarly for morality and social relationships. “We have language, of course, and we are technologically more developed, but many of the basics of our social relationships — in terms of the hierarchies that we have, the friendships, the attachments — are very close to the primates.”

Critics argued that de Waal had a tendency to anthropomorphize animals, ascribing them human emotions and characteristics that simply weren’t present. His response to such critiques was that human exceptionalism blinded us to our shared psychology — a view he dubbed “anthropodenial.”

“That’s how you can sum up my career: I’ve brought apes a little closer to humans but I’ve also brought humans down a bit.”

Frans de Waal

In 1981, de Waal moved to the U.S. to join the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center. In 1991, he joined Emory. There, he served as the C.H. Candler Professor in the psychology department as well as the director of the Living Links Center at the school’s Yerkes National Primate Research Center until his retirement in 2019.

In addition to his research, his well-received books and public talks helped change the cultural discussion around animal behaviors. Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? (2016) and Mama’s Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Tell Us about Ourselves (2019) were both bestsellers, while his online lectures for TED and Big Think have been exceedingly popular.

During a now-famous talk, he discussed research he did on fairness and reciprocity in capuchin monkeys with then-PhD candidate Sarah Brosnan. During the presentation, he showed a video of a monkey who threw a cucumber at a researcher when he realized another monkey received a grape — a much more coveted reward — for performing the same task. The presentation has been viewed more than 23 million times and brought de Waal’s ideas to a massive audience.

Some of de Waal’s ideas haven’t fared so well in meme culture, though. For instance, his first book, Chimpanzee Politics (1982), popularized the term “alpha male” in our social lexicon. Former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Newt Gingrich even made it required reading among freshman Republican representatives during his tenure.

However, the term became misconstrued to mean a man who uses power, force, and coercion to get what he wants and stay atop the social hierarchy. De Waal’s last book, Different (2022), was written, in part, to set the record straight. In it, he shows that an alpha is simply the one at the top of the social hierarchy — whether human, chimp, or bonobo; male or female. And the most successful alphas, even in chimp societies, are often the ones who lead with care, kindness, and compassion.

Honors and recognitions followed for his contributions to culture and science. He was named one of TIME magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in 2007 and Discover magazine’s 47 Great Minds of Science. He was knighted into the Order of the Netherlands Lion and elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He won the Arthur W. Staats Award and the E.O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award.

He even received an Ig Nobel Prize, a satirical award given to research that makes people laugh while they think. The research that earned him that latter award: a study showing that chimps could identify others by their butts.

Beyond his accolades, de Waal was remembered fondly by his students and colleagues as an exceptional teacher and mentor who taught with care and a wry sense of humor.

“I think Frans came across sometimes as reserved but he wasn’t like that once you got to know him,” Brosnan told Emory. “He was so much fun. He would hold ‘simian soirees’ at his house where graduate students would gather to talk. He was a fantastic piano player and he would play for us.”

A gifted and remarkable scientist, he will be sorely missed. But in his absence, others will continue to build on his contributions to further our understanding of human nature — as well as our relationship to the world and the fellow creatures we share it with.

This article Frans de Waal: Acclaimed primatologist and impactful Big Thinker is featured on Big Think.

The post “Frans de Waal: Acclaimed primatologist and impactful Big Thinker” by Kevin Dickinson was published on 03/22/2024 by bigthink.com