Warning: this article contains spoilers.

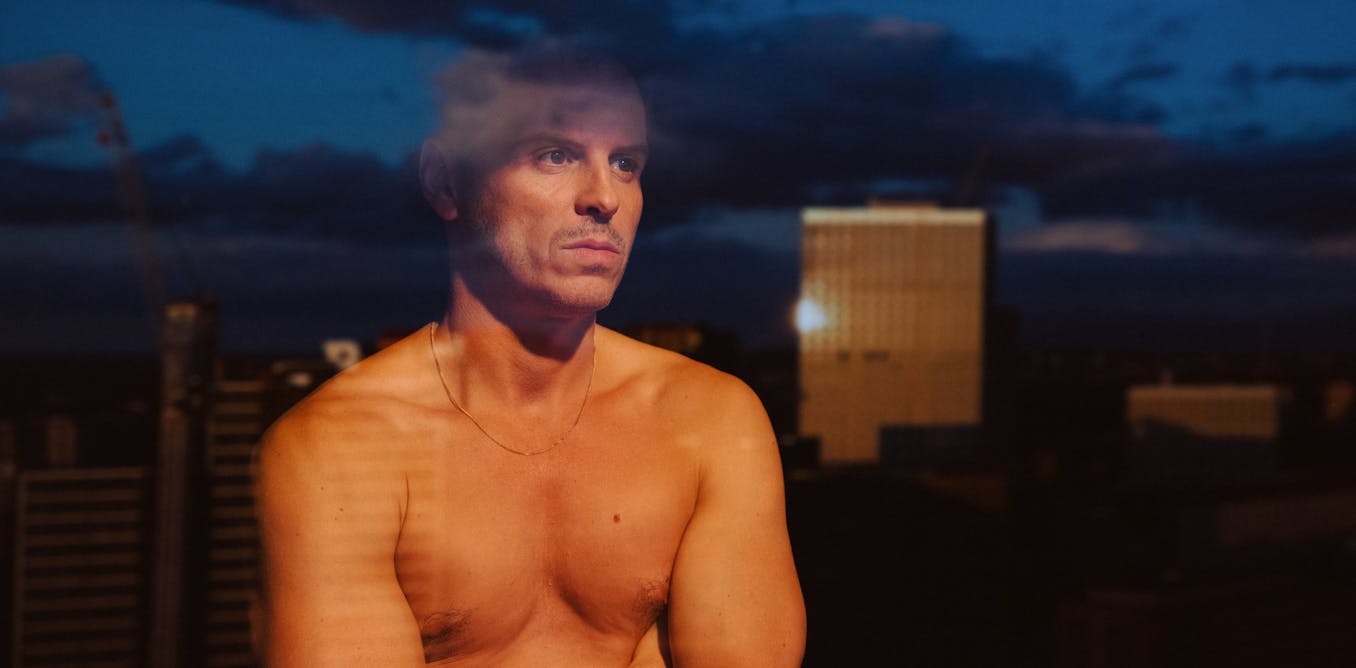

A lonely 40-something screenwriter living in an almost-empty London apartment block, Adam (Andrew Scott) is alienated, exhausted and struggling to write about his past, but can’t get beyond the opening line.

One evening, Harry (Paul Mescal), a younger man from downstairs, appears at his door. He’s tipsy, vulnerable, flirty and charming. “There’s vampires at my door,” he says. Adam doesn’t let him in and later reveals that fear had stopped him.

This rings true, especially for a 40-something gay man like Adam: someone who grew up in the 1980s, during a period of rampant and violent homophobia and the AIDS crisis. England and Wales had partially decriminalised homosexuality in 1967, but Thatcher’s Britain was an ugly place for LGBTQ+ people.

The screenplay Adam is writing is set in 1987, the year that Section 28 was introduced, banning the “promotion” of homosexuality. At that time, the tabloids demonised AIDS victims as deviant plague-carriers and there were terrifying government health warnings on national television.

Homosexuality remained illegal in Ireland and the 1980s witnessed notorious hate-crimes, including the murder of Charles Self by a stranger when they hooked up. These crimes don’t belong to the past: in 2022, two gay men in Sligo were murdered by a man they met through a dating app. Small wonder that a fortysomething gay man like Adam would shut Harry out.

But it wouldn’t be much of a story if it ended there.

As an academic of LGBTQ+ history, I hugely enjoyed this delicate, melancholy and life-affirming film. It speaks to many of the real and heartbreaking experiences gay men in the UK and Ireland have had to navigate. It also highlights the progress and more hopeful world that has been carved for younger generations of queer men. But most of all, its a testament to the power of love.

Open to love

There is a spark between them; Adam reaches out to Harry and we see a relationship develop from an initial hook-up to long-lasting companionship and love. This connection allows Adam to revisit two painful relationships he had left in the past.

Spurred on by a photograph of his parents (Jamie Bell and Claire Foy), he returns to the suburbs where he was born, and meets them again. They were killed in a car crash when he was about 12, but here they seem to be alive, welcoming and not a day older.

When Adam tells his mother that he’s gay, she isn’t hostile, but she is worried. She says that she’s seen the ads about that awful disease and “they say it’s a lonely life”. Adam’s reply – “they don’t say that now” – is contradicted by his own experience before meeting Harry. He has been shut down by homophobia.

He tells his father about the relentless name-calling and physical bullying he endured at school. But he had never revealed it when he was a child and his father had never consoled Adam when he heard him crying in his room.

This again speaks to the experiences of many gay men and isn’t confined to the past. A man easing his son’s pain is still perceived by some as a weakness and we still live in a society where LGBT+ children are tormented by bullies. The 2022 national survey conducted by BelongTo, an Irish LGBT+ rights group advocating for young people, found that 76% of LGBT+ secondary school students felt unsafe at school.

Embracing the word ‘queer’

In the film, twentysomething Harry refers to continuing homophobia when he asks Adam if he is queer; it seems a more polite word than gay, he says, recalling children using the word as a slur. Harry’s remark points to an extraordinary transformation in language.

In the 1980s, “gay” was the most positive word used to describe LGBTQ+ people, and “queer” was used by homophobes as a vicious insult. “Queer-bashing” was the term used by the five youths who killed Declan Flynn in Dublin in 1982: a notorious Irish hate-crime. The judge at their trial did not regard them as murderers and gave them suspended sentences for manslaughter.

Searchlight Pictures

I mention Ireland again because, in the film, Adam was sent to live in Dublin with his maternal grandmother after his parents’ deaths. He tells his mother that he got on better there because he had learned how to fit in, an act of self-censorship still familiar to many LGBT+ people in Ireland, as referenced in drag queen Panti Bliss’s “Noble Call” speech. But today’s Ireland is also a place where “queer” is no longer a hateful word: it’s used by many LGBT+ people to celebrate their identities.

BelongTo’s 2022 survey points to the positive impact of adults’ support for LGBT+ young people and shows that there are pathways out of oppression and suffering.

In the film, the adult Adam comforts his father, who cries when he grasps how much young Adam had suffered. In a beautiful scene we see the two of them hugging. Through the reflection in the mirror Adam is transformed into his younger self, and without any words the film conveys a sense of acceptance and forgiveness between the two.

The film’s final scene makes us rethink its storyline of Adam’s and Harry’s relationship. It again affirms “the power of love”, the title of the Frankie Goes to Hollywood song (and LGBT+ anthem) that plays over the ending and credits. “I’ll protect you from the hooded claw, keep the vampire from your door,” promises Adam, repeating the words of the song and echoing Harry’s first words to him.

Whatever “really” happens in All of Us Strangers, it leaves us with a sense of hope and love transcending loss and death.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The post “heartbreaking film speaks to real experiences of gay men in UK and Ireland” by Diarmuid Scully, Lecturer in medieval history, University College Cork was published on 02/02/2024 by theconversation.com