Lubumbashi is a city in the mineral-rich Katanga region in the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Many people might not have heard of it, but Lubumbashi and its surrounding region have been at the centre of global geopolitics since the start of the 20th century. The area provided immense sources of copper, a metal that helped electrify the planet in the 1900s. It was also the source of all the uranium for the atom bombs used in the second world war.

The global demand for these minerals came at a great price. Lubumbashi grew as a divided city where housing and labour were spatially and racially segregated. Congolese workers were exploited, abused and taxed as urban and mining strategies were used to reshape society.

History is repeating itself. Neocolonialism now shapes the extraction of DRC resources.

Today, the southern DRC produces over 70% of the world’s cobalt. Cobalt is a mineral essential to decarbonisation – a strategy to reduce harmful carbon dioxide emissions. Cobalt is present in batteries in electric vehicles, mobile phones, laptop computers and renewable energy storage systems.

Like copper and uranium before it, cobalt mining has been linked to widescale exploitation and child labour. Corruption and elite capture remain defining features of mining in the DRC.

We are academics who research urbanisation, mining and sustainability as well as urban planning and environmental management. Our recent paper addresses the fact that African cities like Lubumbashi are at the heart of events that have shaped the modern world, yet they are woefully neglected in global urban theory (thinking about how cities form and develop) and urban geography.

Focusing on the global north and neglecting the south leads to major data gaps and contributes to mismatched and outdated urban policy.

© Brandon Marc Finn

We also argue that the human rights abuses and perils of today’s cobalt mining are new forms of old colonial practices. They strip the land and people of resources without proper pay. They offer green minerals to the global north at the cost of lives in the global south.

Sustainable cities and global decarbonisation are essential if we are to reduce cities’ carbon footprints and decarbonise economies in the face of the climate crisis.

Lubumbashi’s history, therefore, can offer a fuller understanding of the human and historical costs of minerals that shape cities – and the world.

A brief history of Lubumbashi

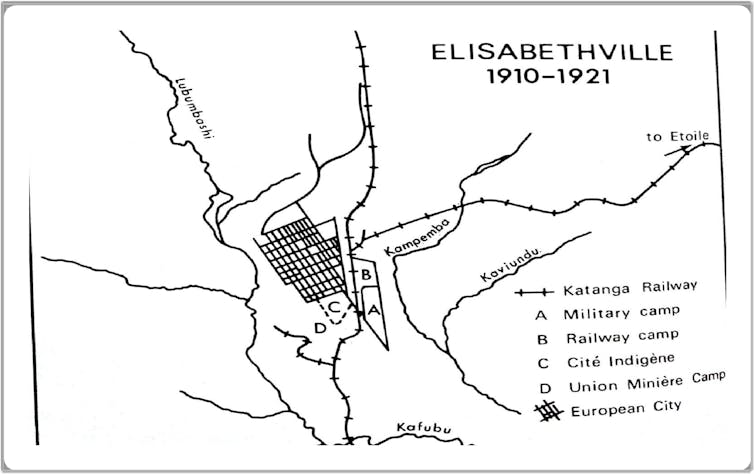

Lubumbashi was originally called Elisabethville. It was established by colonial Belgium in 1910 precisely to extract copper for global markets. This was done through a company named Union Minière du Haut Katanga (UMHK).

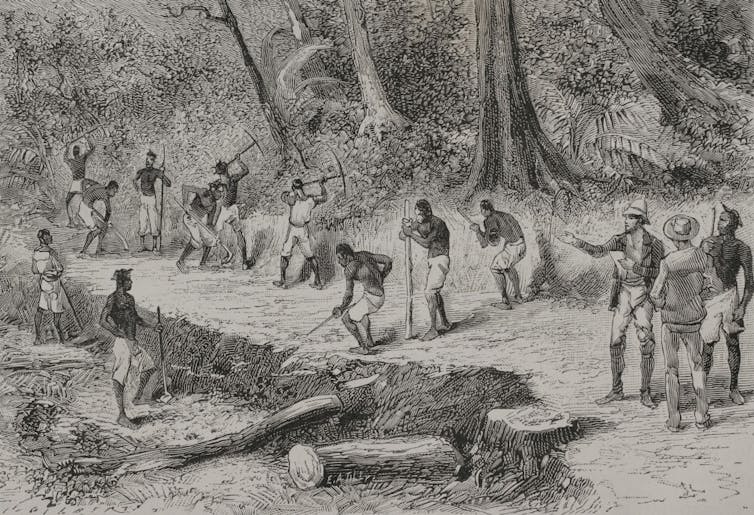

Concessionary companies made enormous profits in the Congo Free State between 1885 and 1908. The entire country stood under the private ownership of King Leopold II of Belgium. These companies were given the right to extract minerals and rubber through taxes imposed on local people.

PHAS/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

The Belgian Compagnie du Katanga (which later founded UMHK) had the task of establishing the physical and economic infrastructure of the region. In exchange for laying the groundwork for the extractive industries, soon to be headquartered in Elisabethville, the company was given a third of all unoccupied land in Katanga. The Belgians established a copper smelter and constructed roads. Temporary headquarters were established to supervise Elisabethville’s expansion.

One initial method of controlling the local rural people was a “hut tax” that had to be paid to live in Lubumbashi. Later, a “head tax” was introduced to raise funds for colonial management. It forced people into labour as the only means to pay off their newly acquired debt to the colonial state.

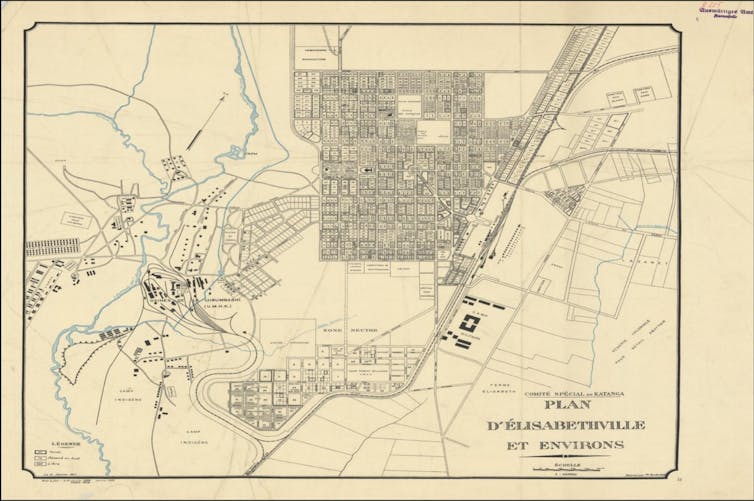

Elisabethville served as the device to assert effective occupation. It also staved off the possibility of British occupation of the territory. The Belgians planned Elisabethville by reproducing the urban forms and racial segregation of Bulawayo’s grid in Southern Rhodesia (part of today’s Zimbabwe) and Johannesburg in South Africa.

F Grevisse/Institut Royal Colonial Belge

UMHK dominated the colonial economy as demand for copper increased worldwide. UMHK also stipulated which seeds would be planted where for agriculture. It dissolved local markets and whipped labourers.

Copper was in such high demand because it is a non-corrosive material that conducts electricity well. It lined telegraph and electrical transmission cables across the globe.

Copper mining acted as a springboard from which UMHK could spread its influence. It developed railways, cities, labour camps and mining sites throughout Katanga.

P Vandenbak

This allowed UMHK access to the extraction of another resource that would shape the global geopolitical landscape: uranium – extracted from the Shinkolobwe mine in Katanga.

It was the Belgian colonial presence that allowed the US to have access to uranium deposits as they sought to beat Germany in the race to build atomic weapons. All the uranium used in the two nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki came from Katanga.

This highlights the global significance of, but a neglected focus on, the impacts of mineral supply chains in the global south. Control over Lubumbashi’s minerals cannot be underplayed in this global historical event.

Katanga seceded from the Congo for three years, 11 days after the country gained independence from Belgium in 1960. The fight to gain control over Katanga’s resources led to the US and Belgian-backed assassination of the first independence leader, Patrice Lumumba. He was intent on reunifying Congo.

Mobutu Sese Seko became president of Zaire (today’s DRC) after a coup in 1965. He nationalised UMHK a year later. Mobutu served as president for almost 32 years, and his regime was characterised by autocratic corruption and economic exploitation.

Cobalt and global decarbonisation

The growth of modern technology relies, at least in part, on the extraction of cobalt in the DRC before it is shipped, mainly to China.

Cobalt is extracted as a byproduct of copper mining. Artisanal and small-scale mining and child labour remain a salient feature of cobalt extraction in the DRC. These miners receive little to no support and reflect the historical structural marginalisation created in the region.

Junior Kannah/AFP/Getty Images

Lubumbashi serves as the mining headquarters of the southern DRC, and other cities, like Kolwezi, have grown rapidly in response to the surge in cobalt demand. Spatial and labour-related inequalities from the past are being replicated and expanded on in the present.

The DRC’s impoverishment continues apace as South African, Kazakh, Swiss and, with increasing influence, Chinese mining companies maintain their practice of exclusionary extraction, social displacement and political corruption.

Why this matters

Our research shows the importance of understanding the history of extraction and urban settlement in the region to shed light on new forms of old practices associated with decarbonisation. We see this as a continuing form of colonial power – as neocolonialism.

Contemporary debates around global inequalities associated with decarbonisation highlight how African populations must endure poor living conditions while the global north transitions to low-carbon technologies. We must find ways to move away from carbon-based economies that do not reproduce colonial inequalities.

Read more:

Patrice Lumumba’s tooth represents plunder, resilience and reparation

Lubumbashi demonstrates the importance of African cities and resources in understanding critical global developmental and geopolitical issues.

For decarbonisation to be socially and environmentally just, it must contend with the people, places, and environments on which the future of low-carbon technology is based. Lubumbashi’s history shows how challenging this task will be.

The post “history is repeating itself in Lubumbashi as the world scrambles for minerals to go green” by Brandon Marc Finn, Research Scientist at the School for Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan was published on 02/04/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply