If you visit the Erie Canal today, you’ll find a tranquil waterway and trail that pass through charming towns and forests, a place where hikers, cyclists, kayakers, bird-watchers and other visitors seek to enjoy nature and escape the pressures of modern life.

However, relaxation and scenic beauty had nothing to do with the origins of this waterway.

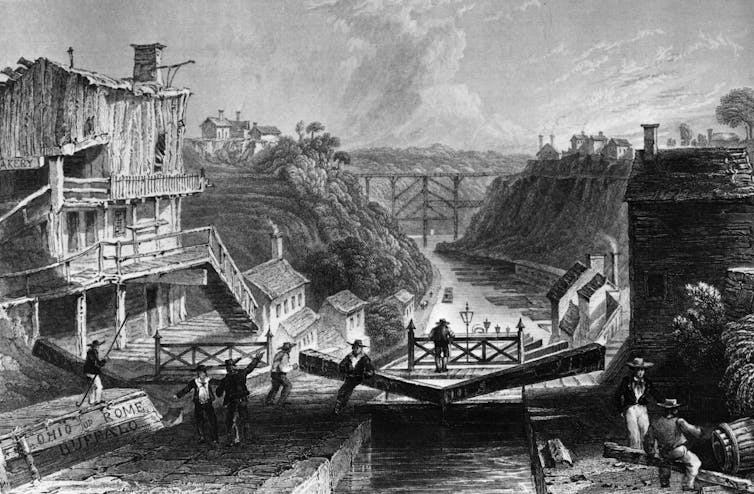

When the Erie Canal opened 200 years ago, on Oct. 26, 1825, the route was dotted with decaying trees left by construction that had cut through more than 360 miles of forests and fields, and life quickly sped up.

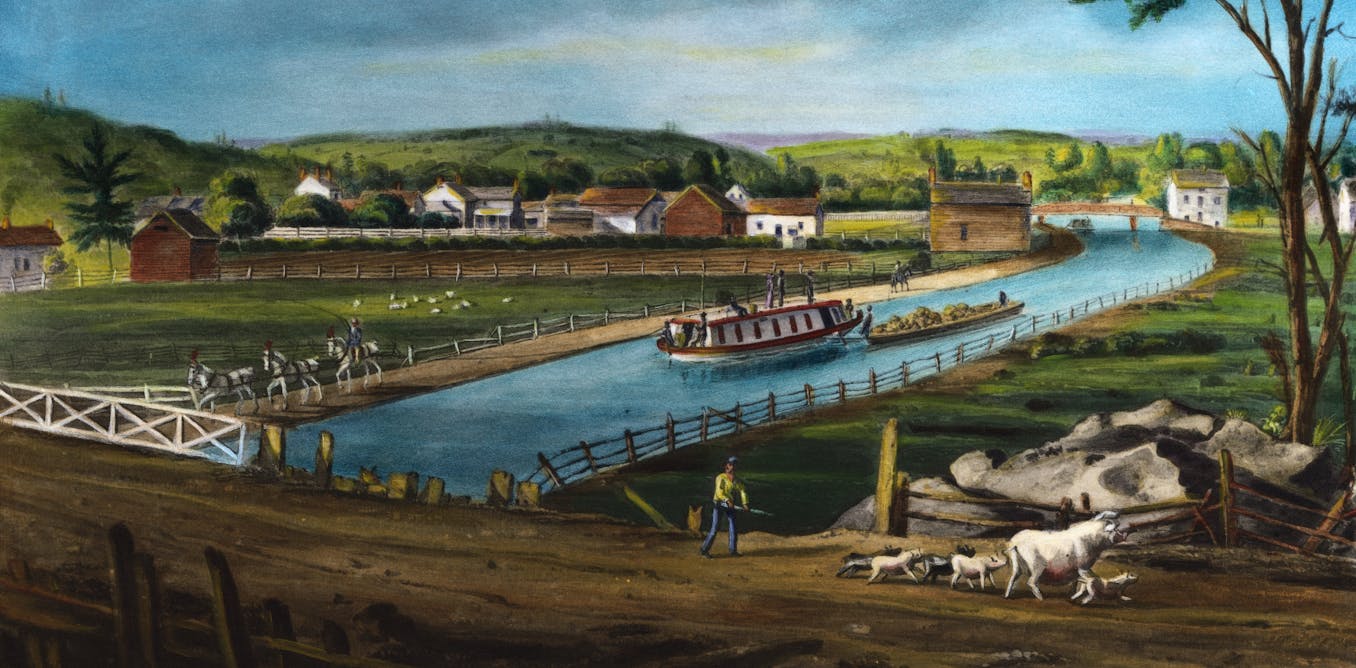

Mules on the towpath along the canal could pull a heavy barge at a clip of 4 miles per hour – far faster than the job of dragging wagons over primitive roads. Boats rushed goods and people between the Great Lakes heartland and the port of New York City in days rather than weeks. Freight costs fell by 90%.

New York State/Wikimedia

As many books have proclaimed, the Erie Canal’s opening in 1825 solidified New York’s reputation as the Empire State. It also transformed the surrounding environment and forever changed the ecology of the Hudson River and the lower Great Lakes.

For environmental historians like me, the canal’s bicentennial provides an opportunity to reflect upon its complex legacies, including the evolution of U.S. efforts to balance economic progress and ecological costs.

Human and natural communities ruptured

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Indigenous nations that the French called the Iroquois, engaged in canoe-based trade throughout the Great Lakes and Hudson River valley for centuries. In the 1700s, that began to change as American colonists took the land through brutal warfare, inequitable treaties and exploitative policies.

That Haudenosaunee dispossession made the Erie Canal possible.

After the Revolutionary War, commercial enthusiasm for a direct waterborne route to the West intensified. Canal supporters identified the break in the Appalachian Mountains at the junction of the Mohawk River and the Hudson as a propitious place to dig a channel to Lake Erie.

Yet cutting a 363-mile-long waterway through New York’s uneven terrain posed formidable challenges. Because the landscape rises 571 feet between Albany and Buffalo, a canal would require multiple locks to raise and lower boats.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Federal officials refused to finance such “internal improvements.” But New York politician DeWitt Clinton was determined to complete the project, even if it meant using only state funds. Critics mocked the $7 million megaproject, worth around US$170 million today, calling it “DeWitt’s Ditch” and “Clinton’s Folly.” In 1817, however, thousands of men began digging the 4-foot-deep channel using hand shovels and pickaxes.

The construction work produced engineering breakthroughs, such as hydraulic cement made from local materials and locks that lifted the canal’s water level about 60 feet at Lockport, yet it obliterated acres of wetlands and forests.

After riding a canal boat between Utica and Syracuse, the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne described the surroundings in 1835 as “now decayed and death-struck.”

However, most canalgoers viewed the waterway as a beacon of progress. As a trade artery, it made New York City the nation’s financial center. As a people mover, it fueled religious revivals, social reform movements and the growth of Great Lakes cities.

Detroit Publishing Company/Library of Congress

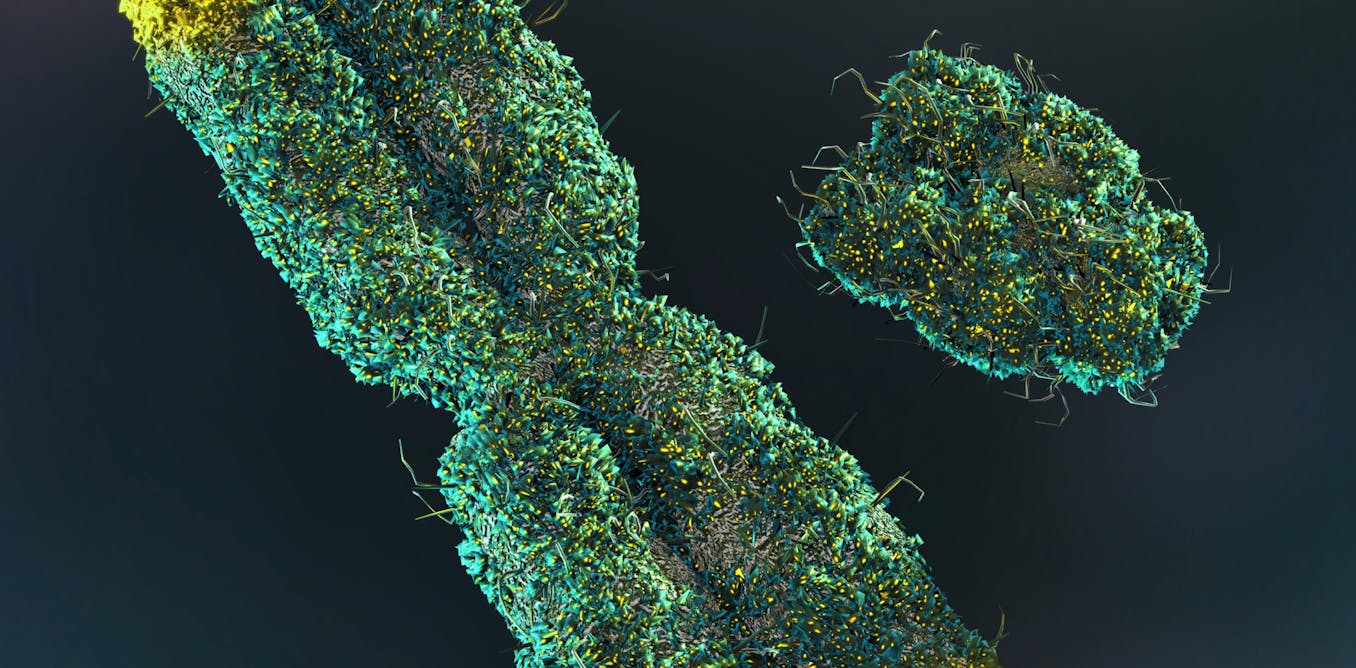

The Erie Canal’s socioeconomic benefits came with more environmental costs: The passageway enabled organisms from faraway places to reach lakes and rivers that had been isolated since the end of the last ice age.

An invasive species expressway

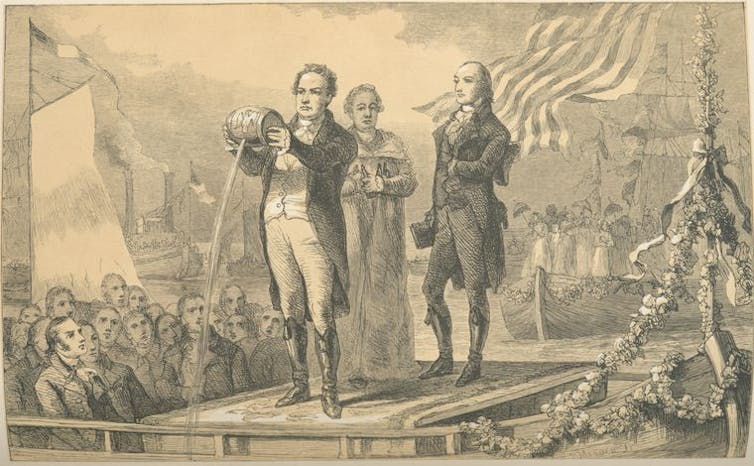

On Oct. 26, 1825, Gov. Clinton led a flotilla aboard the Seneca Chief from Buffalo to New York City that culminated in a grandiose ceremony.

To symbolize the global connections made possible by the new canal, participants poured water from Lake Erie and rivers around the world into the Atlantic at Sandy Hook, a sand spit off New Jersey at the entrance to New York Harbor. Observers at the time described the ritual of “commingling the waters of the Lakes with the Ocean” in matrimonial terms.

Philip Meeder, wood-engraver, 1826, New York Public Library via Wikimedia Commons

Clinton was an accomplished naturalist who had researched the canal route’s geology, birds and fish. He even predicted that the waterway would “bring the western fishes into the eastern waters.”

Biologists today would consider the “Wedding of the Waters” event a biosecurity risk.

The Erie Canal and its adjacent feeder rivers and reservoirs likely enabled two voracious nonnative species, the Atlantic sea lamprey and alewife, to enter the Great Lakes ecosystem. By preying on lake trout and other highly valued native fish, these invaders devastated the lakes’ commercial fisheries. The harvest dropped by a stunning 98% from the previous average by the early 1960s.

T. Lawrence/NOAA Great Lakes, CC BY-SA

Tracing their origins is tricky, but historical, ecological and genetic data suggest that sea lampreys and alewives entered Lake Ontario via the Erie Canal during the 1860s. Later improvements to the Welland Canal in Canada enabled them to reach the upper Great Lakes by the 1930s.

Protecting the $5 billion Great Lakes fishery from these invasive organisms requires constant work and consistent funding. In particular, applying pesticides and other techniques to control lamprey populations costs around $20 million per year.

The invasive species that has inflicted the most environmental and economic harm on the Great Lakes is the zebra mussel. Zebra mussels traveled from Eurasia via the ballast water of transoceanic ships using the St. Lawrence Seaway during the 1980s. The Erie Canal then became a “mussel expressway” to the Hudson River.

The hungry invading mussels caused a nearly tenfold reduction of phytoplankton, the primary food of many species of the Hudson River ecosystem. This competition for food, along with pollution and habitat degradation, led to the disappearance of two common species of the Hudson’s native pearly mussels.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Today, the Erie Canal remains vulnerable to invasive plants, such as water chestnut and hydrilla, and invasive animals such as round goby. Boaters, kayakers and anglers can help reduce bioinvasions by cleaning, draining and drying their equipment after each use to avoid carrying invasive species to new locations.

A recreational treasure

During the Gilded Age in the late 1800s, the Erie Canal sparked a utilitarian sense of environmental concern. Timber cutting in the Adirondack Mountains was causing so much erosion that the eastern canal’s feeder rivers were filling up with silt.

To protect these waterways, New York created Adirondack Park in 1892. Covering 6 million acres, the park balances forest preservation, recreation and commercial use on a unique mix of public and private lands.

Erie Canal shipping declined during the 20th century with the opening of the deeper and wider St. Lawrence Seaway and competition from rail and highways. The canal still supports commerce, but the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor now provides an additional economic engine.

NYS Department of Transportation via National Park Service

In 2024, 3.84 million people used the Erie Canalway Trail for cycling, hiking, kayaking, sightseeing and other adventures. The tourists and day-trippers who enjoy the historic landscape generate over $300 million annually.

Over the past 200 years, the Erie Canal has both shaped, and been shaped by, ecological forces and changing socioeconomic priorities. As New York reimagines the canal for its third century, the artificial river’s environmental history provides important insights for designing technological systems that respect human communities and work with nature rather than against it.

The post “How a technological marvel for trade changed the environment forever” by Christine Keiner, Chair, Department of Science, Technology, and Society, Rochester Institute of Technology was published on 10/15/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply