Beneath the roar of gunfire and the chaos of D-day, an unlikely hero played a vital role — wetland science. Often overlooked amid military strategies and troop movements, the study of mud proved critical to the success of the largest amphibious invasion in history.

Much has been written about the events of June 6 1944 and the extensive planning that led up to Operation Overlord on that pivotal day. The success of the Normandy landings involved expertise from a vast array of military, espionage, engineering and communication groups. My new report explains how scientists with knowledge of sediments and substrate formation, such as peat found in bogs and fens, were also instrumental in the planning and execution of D-day.

Following the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk during Operation Dynamo in 1940, Britain and its allies began meticulously planning for the invasion of mainland Europe. Gathering intelligence about the French coast and where the invasion would probably occur, was a vital component of these preparations.

The allies concluded that any landing site needed to be within range of their fighter aircraft, sheltered from harsh weather, and near a port to facilitate the landing of additional troops and equipment. These criteria led to the selection of the coast north of Caen in Normandy, France.

However, initial intelligence had raised concerns about whether the beaches were suitable for a successful invasion. Geological maps smuggled out of Paris by the French Resistance suggested that the beaches might be underlain by peat, which could destabilise the landing. Staggeringly, one of these maps is believed to have dated back to Roman times, when they surveyed the entire empire for peat, as it was used as a fuel source.

Shawshots/Alamy

Peat, a semi-decomposed organic matter that accumulates over millennia in wetland habitats, can be soft and unstable. Professor John Desmond Bernal, an important scientific adviser to the allies, warned that the beaches might not support the heavy vehicles and equipment of the invasion force.

Aerial photography was inconclusive, so physical analysis of the beaches was deemed necessary. The task fell to Lieutenant Commander Nigel Clogstoun-Willmott of the Royal Navy, who had expertise in covert coastal surveying. He had previously created the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties (COPP) to gather detailed information about potential landing sites earlier in the war.

A daring mission

After training and a test mission, COPP swung into action. On December 31, two commandos — 24-year-old Major Logan “Scottie” Scott-Bowden and 25-year-old Sergeant Bruce Ogden-Smith — were chosen to land covertly on the Normandy landing beach codenamed Gold Beach. Their task was to collect sediment samples.

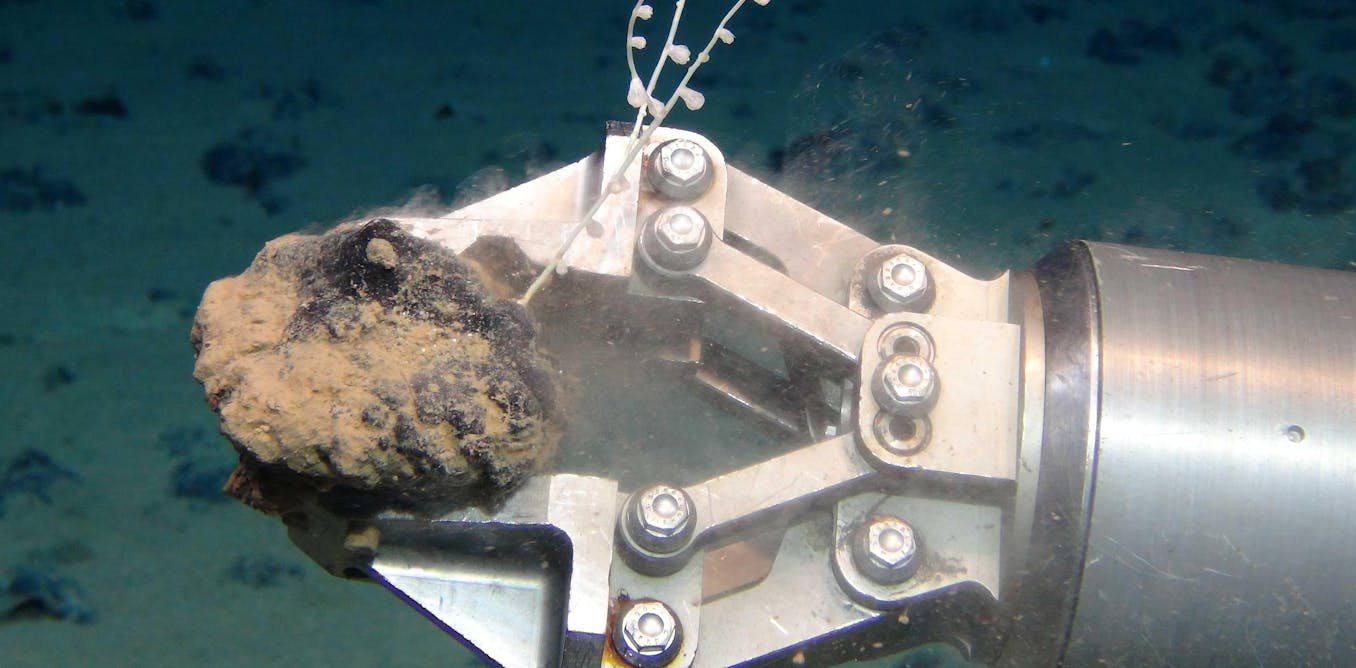

On New Year’s Eve 1943, Scott-Bowden and Ogden-Smith swam ashore under the cover of darkness, having been dropped off by a small boat 300 meters from the French coast. Alongside their swimming suits, rather like modern-day dry-suits, they were equipped with a torch, compass, watch, a fighting knife and a .45 Colt revolver. They also took a soil corer, or auger, for taking soil samples and ten tubes for storing the samples.

When they eventually reached the predetermined point on Gold Beach, they crawled in a W pattern, collecting samples. They recorded their positions on waterproof writing tablets strapped to their wrists. When they had finished sampling the area, they waded into the surf and swam back out to sea. Reaching what they hoped was their rendezvous point, they signalled with their torches fitted with a directional cone and waterproofed with a condom until they were picked up by the rest of the COPP team.

Upon their return to England, the samples were analysed by soil and wetland scientists to determine the peat and clay content. It was crucial for assessing the suitability of the beaches as landing sites.

Andrew Hayes/Alamy

Over the following months, COPP surveyed many areas of the Normandy landing beaches, looking for soft clay and peat deposits. It is understood that some of the places were found to be acceptable for wheeled vehicles while other areas weren’t.

In some cases, specialised vehicles and tanks – so-called “funnies” – were specifically designed to cope with the substrate conditions detected by members of COPP. One example of this was the “Bobbin” carpet layer, which laid its own path over soft clay, mud and peat.

The bravery of the COPP commandos and the application of wetland science were instrumental in ensuring the success of D-day. Without their efforts the allies could literally have been bogged down, making them easy targets for German defences. As Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, the allied naval commander, stated after the Normandy landings: “On these operations depends to a very great extent the final success of Operation Overlord.”

The actions of the commandos and scientists involved must not be forgotten as we honour the 80th anniversary of D-day. Their work ensured that the beaches of Normandy could support the weight of freedom, changing the course of history.

The post “how wetland science stopped the Normandy landings from getting bogged down” by Christian Dunn, Professor in Natural Sciences, Bangor University was published on 06/05/2024 by theconversation.com