It’s summer, and it’s been hot, even in northern cities such as Boston. But not everyone is hit with the heat in the same way, even within the same neighborhood.

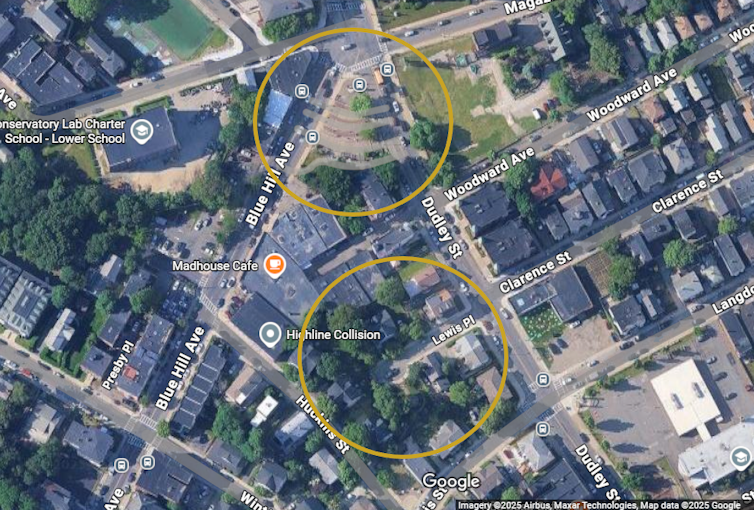

Take two streets in Boston at 4:30 p.m. on a recent day, as an example. Standing in the sun on Lewis Place, the temperature was 94 degrees Fahrenheit (34.6 degrees Celsius). On Dudley Common, it was 103 F (39.2 C). Both streets were hot, but the temperature on one was much more dangerous for people’s health and well-being.

The kicker is that those two streets are only a few blocks apart. The difference epitomizes the urban heat island effect, created as pavement and buildings absorb and trap heat, making some parts of the city hotter.

Dan O’Brien

A closer look at the two streets shows some key differences:

-

Dudley Common is public open space sandwiched between two thoroughfares that create a wide expanse of pavement lined with storefronts. There aren’t many trees to be found.

-

Lewis Place is a residential cul-de-sac with two-story homes accompanied by lots of trees.

This comparison of two places within a few minutes’ walk of each other puts the urban heat island effect under a microscope. It also shows the limits of today’s strategies for managing and responding to heat and its effects on public health, which are generally attuned to neighborhood or citywide conditions.

Imagery ©2025 Airbus Maxar Technologies, map data Google ©2025

Even within the same neighborhood, some places are much hotter than others owing to their design and infrastructure. You could think of these as urban heat islets in the broader landscape of a community.

Sensing urban heat islets

Emerging technologies are making it easier to find urban heat islets, opening the door to new strategies for improving health in our communities.

While the idea of reducing heat across an entire city or neighborhood is daunting, targeting specific blocks that need assistance the most can be faster and a much more efficient use of resources.

Doing that starts with making urban heat islets visible.

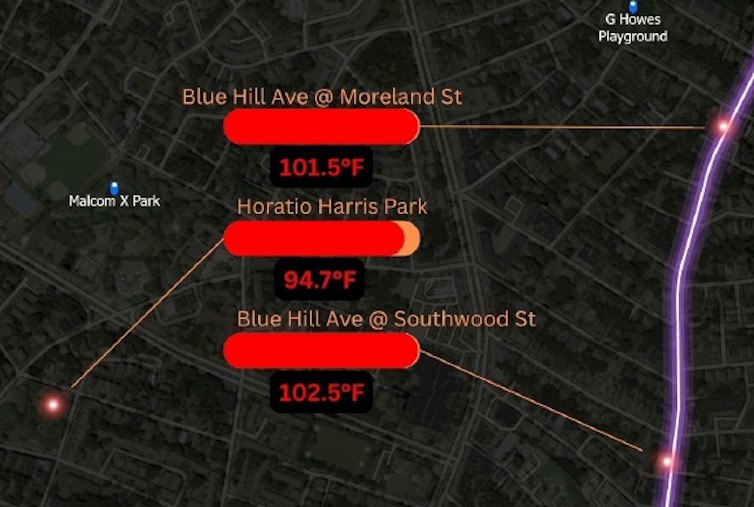

In Boston, I’m part of a team that has installed more than three dozen sensors across the Roxbury neighborhood to measure temperature every minute for a better picture of the community’s heat risks, and we’re in the process of installing 25 more. The Common SENSES project is a collaboration of community-based organizations, including the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative and Project Right Inc.; university researchers like me who are affiliated with Northeastern University’s Boston Area Research Initiative; and Boston city officials. It was created to pursue data-driven, community-led solutions for improving the local environment.

Data from those sensors generate a real-time map of the conditions in the neighborhood, from urban heat islets like Dudley Common to cooler urban oases, such as Lewis Place.

Common SENSES

These technologies are becoming increasingly affordable and are being deployed in communities around the world to pinpoint heat risks, including Miami, Baltimore, Singapore and Barcelona. There are also alternatives when long-term installations prove too expensive, such as the U.S.’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration volunteer science campaign, which has used mobile sensors to generate one-time heat maps for more than 50 cities.

Making cooler communities, block by block

Although detailed knowledge of urban heat islets is becoming more available, we have barely scratched the surface of how they can be used to enhance people’s health and well-being.

The sources of urban heat islets are rooted in development – more buildings, more pavement and fewer trees result in hotter spaces. Many projects using community-based sensors aspire to use the data to counteract these effects by identifying places where it would be most helpful to plant trees for shade or install cool roofs or cool pavement that reflect the heat.

John McCoy/MediaNews Group/Los Angeles Daily News via Getty Image

However, these current efforts do not fully capitalize on the precision of sensors. For example, Los Angeles’ massive investment in cool pavement has focused on the city broadly rather than overheated neighborhoods. New York City’s tree planting efforts in some areas failed to anticipate where trees could be successfully planted.

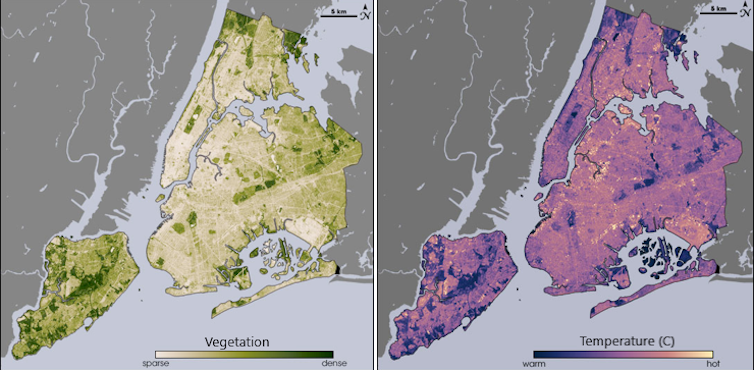

Most other efforts compare neighborhood to neighborhood, as if every street within a neighborhood experiences the same temperature. London, for example, uses satellite data to locate heat islands, but the resolution isn’t precise enough to see differences block by block.

In contrast, data pinpointing the highest-risk areas enables urban planners to strategically place small pocket parks, cool roofs and street trees to help cool the hottest spaces. Cities could incentivize or require developers to incorporate greenery into their plans to mitigate existing urban heat islets or prevent new ones. These targeted interventions are cost-effective and have the greatest potential to help the most people.

NASA/USGS Landsat

But this could go further by using the data to create more sophisticated alert systems. For example, the National Weather Service’s Boston office released a heat advisory for July 25, the day I measured the heat in Dudley Common and Lewis Place, but the advisory showed nearly the entirety of the state of Massachusetts at the same warning level.

What if warnings were more locally precise?

On certain days, some streets cross a crucial threshold – say, 90 F (32.2 C) – whereas others do not. Sensor data capturing these hyperlocal variations could be communicated directly to residents or through local organizations. Advisories could share maps of the hottest streets or suggest cool paths through neighborhoods.

Dan O’Brien

There is increasing evidence of urban heat islets in many urban communities and even suburban ones. With data showing these hyperlocal risks, policymakers and project coordinators can collaborate with communities to help address areas that many community members know from experience tend to be much hotter than surrounding areas in summer.

As one of my colleagues, Nicole Flynt of Project Right Inc., likes to say, “Data + Stories = Truth.” If communities act upon both the temperature data and the stories their residents share, they can help their residents keep cool — because it’s hot out there.

The post “Inside an urban heat island, one street can be much hotter than its neighbor – new tech makes it easier to target cooling projects” by Dan O’Brien, Professor of Public Policy and Urban Affairs and Director of the Boston Area Research Initiative, Northeastern University was published on 08/11/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply