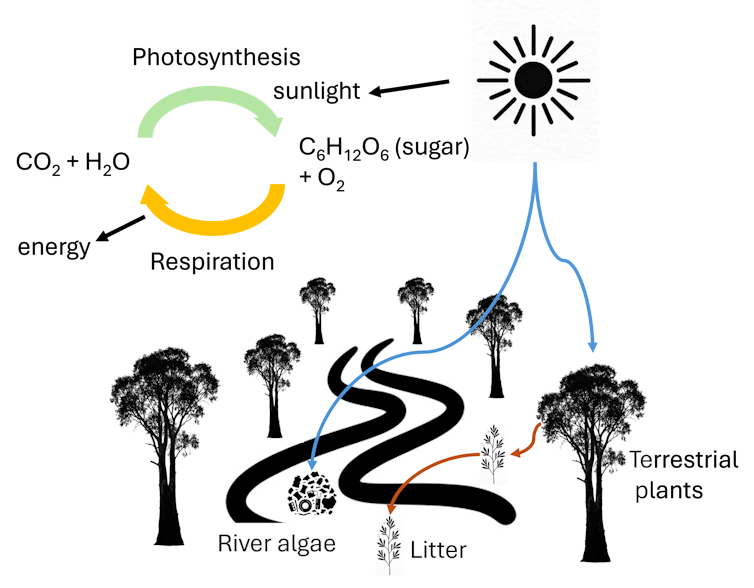

What’s the currency for all life on Earth? Carbon. Every living thing needs a source of carbon to grow and reproduce. In the form of organic molecules, carbon contains chemical energy that is transferred between organisms when one eats the other.

Plants carry out photosynthesis, using energy from sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into sugar and oxygen. Animals get carbon by consuming organic matter in their diet – herbivores from plants, carnivores from eating other animals. They use this carbon for energy and to produce the molecules their bodies need, with some carbon dioxide released by breathing.

But there are other, stranger ways of getting carbon. In our new research, we found something very surprising. River animals were feeding on methane-eating bacteria, which in turn were consuming fossil fuel as food.

Usually, the carbon used as food by river creatures is new in the sense it has been recently converted from gas (carbon dioxide) to solid carbon through photosynthesising algae or trees along the bank. But in a few rivers, such as the Condamine River in Queensland, there’s another source: ancient natural gas bubbling up from underground, which is eaten by microorganisms. Insects such as mayflies have taken to this methane-based carbon with gusto.

AAP

How does a river usually get its carbon?

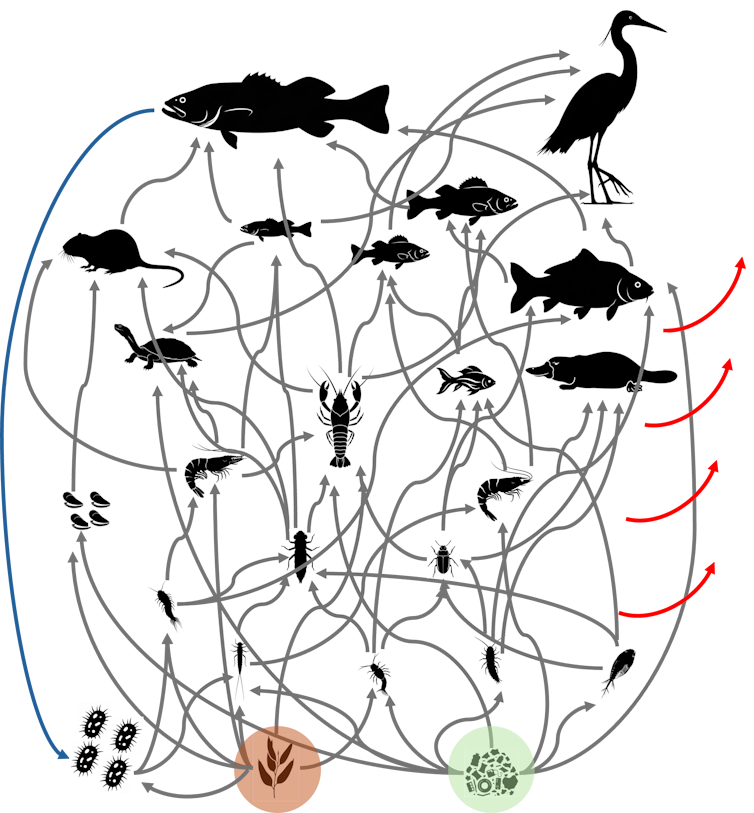

The way photosynthesised carbon moves from a plant to an animal and then another animal can be described as a food web. Food webs show the many different feeding relationships between organisms, and show how species depend on each other for sustenance in an intricate balance.

In a river food web, carbon usually comes from one of two sources: plants growing and photosynthesising in the river (such as algae), or when organic matter such as leaves are washed in by rain or blown in by wind.

Rivers that are well connected to their floodplains often get plenty of carbon from leaf litter from trees which dissolves in water or is eaten directly by animals. Algae in rivers provide a high-quality source of carbon for animals because they can contain high concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids essential for growth and reproduction.

The primary source of carbon for river animals varies depending on prevailing conditions and the individual river.

Paul McInerney

The carbon of the Condamine

Some microorganisms called archaea naturally produce small amounts of methane in oxygen-depleted sediments of rivers.

But we wanted to look at the Condamine to see whether much larger volumes of methane could be used as food.

After it forms deep underground, natural gas can slowly escape through cracks in the earth. If a river bed is directly above, this methane-rich gas will seep into the river.

That’s what happens in Queensland’s Condamine River. The river rises on Mount Superbus, inland from Brisbane, and flows inland until it meets the Darling River.

In some parts of the river, methane bubbles up constantly through the water column from a natural gas reservoir that formed since the Late Pleistocene.

In these stretches of river, dissolved methane concentrations are extremely high: up to 350 times greater than trace concentrations upriver, away from the methane seep.

We wanted to see whether methanotrophic bacteria consuming methane from natural gas were being eaten by river animals, and whether we could trace the carbon signature through the food web.

Paul McInerney

To find out, we analysed the carbon in the bodies of river animals such as zooplankton, insects, shrimp, prawns and fish, and compared it to the different sources of carbon that could make up their food.

The results were clear: animals within reach of the natural gas seeping from underground had a distinct carbon signature showing they were eating food derived from the natural gas. In fact, for insects such as mayflies, methane-based food made up more than half (55%) of their diet.

Over time, this methane-derived food moved up the food web, showing up in prawns and even fish. Here too, it contributed a significant portion of their carbon.

Gavin Rees, CC BY-NC-ND

We found this methane–derived carbon moved through multiple levels of the local food web. It made up almost a fifth (19%) of the carbon in shrimp and 28% of the carbon in carnivorous fish.

For river shrimp and prawns, leaves washed into the river were still important sources of carbon. For mayflies, algae was still an important source of food.

But our work shows that natural gas seeps can be a major, even dominant, source of energy for the entire food web. This is very surprising. It shows an unexpected connection between Earth’s geology and living creatures in a river.

Why does this matter?

Until now, researchers have focused on river and land plants as the main way a river gets its carbon. Our research has uncovered a surprisingly significant way some rivers get their carbon – methane.

In deep sea research, this pathway is better understood. Methane-eating bacteria can form the basis of entire ecosystems which have sprung up around deep sea hydrothermal vents of hot water.

But until now, we have overlooked the role methane-eating bacteria can play in rivers. With this knowledge, we can better track the flows of carbon in rivers so we can gauge ecosystem productivity and see how a food web is functioning.

The post “Scientists surprised to discover mayflies and shrimp making their bodies out of ancient gas” by Paul McInerney, Senior Research Scientist in Ecosystem Ecology, CSIRO was published on 05/02/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply