When you walk around the Groupama Stadium in Lyon (France), you can’t miss them. Four majestic lions in the colours of Olympique Lyonnais stand proudly in front of the stadium, symbols of the influence of a club that dominated French football in the early 2000s. The lion is everywhere in the club’s branding: on the logo, on social media, and even on the chests of some fans who live and breathe for their team. These are the ones who rise as one when Lyou, the mascot, runs through the stands every time the team scores a goal. Yet while it roars in the Lyon stadium, in the savannah, the lion is dying out.

On the ninth day of Ligue 1 (whose matches took place from October 24 to 26, 2025), there were twice as many people in the stadium for the Lyon-Strasbourg match (just over 49,000 spectators) as there are lions in the wild on the planet (around 25,000). Lion populations in Africa and India fell by 25% between 2006 and 2018, like many other species on the planet, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Zakarie Faibis, CC BY-SA

This is a striking paradox: while the sports sector is booming – often capitalising on animal imagery to develop brands and logos and unite crowds around shared values – those same species face numerous threats in the wild, weakening ecosystems without fans or clubs being truly aware of it.

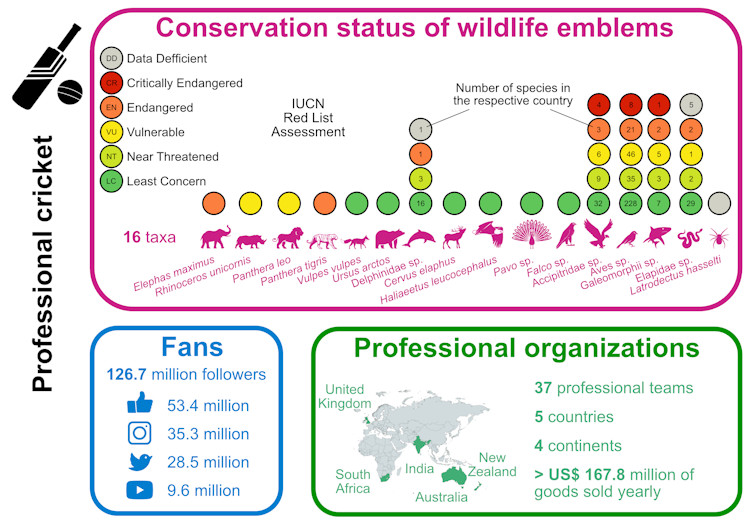

This paradox between the omnipresence of animal representations in sport and the global biodiversity crisis was the starting point of a study published in BioScience. The study quantified the diversity of species represented in the largest team sports clubs in each region of the world, on the one hand, and assessed their conservation status, on the other. This made it possible to identify trends between regions of the world and team sports (both women’s and men’s).

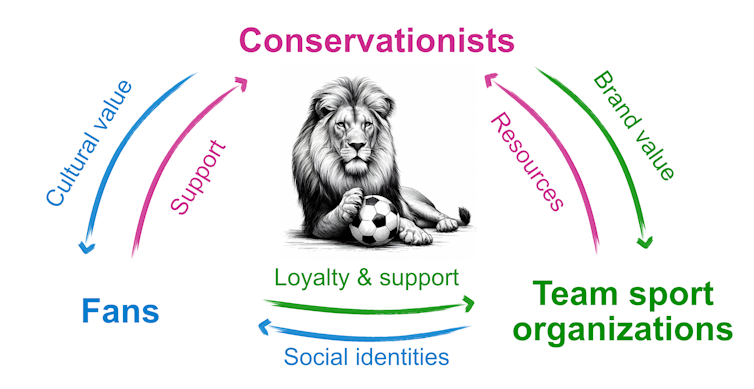

The goal was to explore possible links between professional sport and biodiversity conservation. Sport brings together millions of enthusiasts, while clubs’ identities are based on species that are both charismatic and, in most cases, endangered. The result is a unique opportunity to promote biodiversity conservation in a positive, unifying, and rewarding context.

Nature on jerseys: The diversity of species represented in team sports

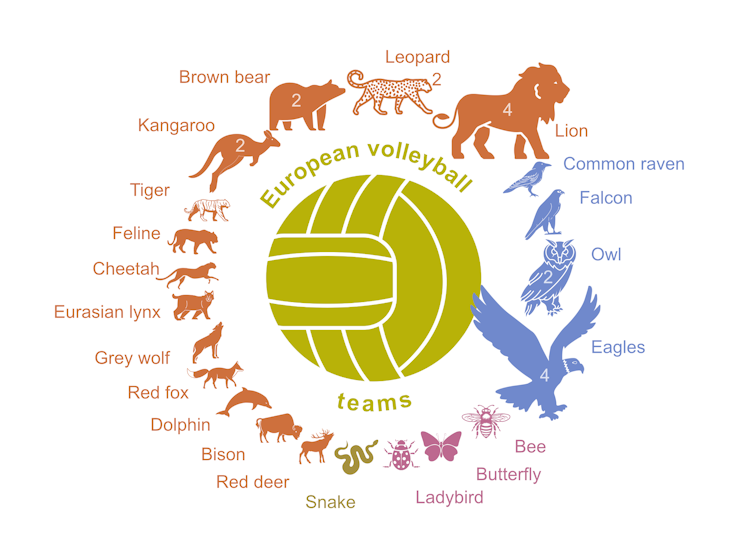

This research, based on 43 countries across five continents, reveals several key insights – chief among them, the importance and sheer scale of wildlife represented in sports emblems. A full 25% of professional sports organisations use a wild animal in their name, logo, or nickname. This amounts to more than 700 men’s and women’s teams across ten major team sports: football (soccer), basketball, American football, baseball, rugby union and league, volleyball, handball, cricket, and ice hockey.

Vector Portal/Creative Commons, CC BY

Unsurprisingly, the most represented species are, in order: lions (Panthera leo), tigers (Panthera tigris), wolves (Canis lupus), leopards (Panthera pardus), and brown bears (Ursus arctos).

While large mammals dominate this ranking, there is in fact remarkable taxonomic diversity overall: more than 160 different types of animals. Squid, crabs, frogs, and hornets sit alongside crocodiles, cobras, and pelicans – a rich sporting bestiary reflecting very specific socio-ecological contexts. We have listed them on an interactive map interactive map available online.

Ugo Arbieu, Click here to access the interactive map

Animal imagery is often associated with major US leagues, such as the NFL, NBA, or NHL, featuring clubs like the Miami Dolphins (NFL), the Memphis Grizzlies (NBA), or the Pittsburgh Penguins (NHL). Yet other countries also display diverse fauna, with over 20 species represented across more than 45 professional clubs in France for instance.

Cultural, aesthetic, or identity-based motivations behind animal emblems

Club emblems often echo the cultural heritage of a region, as in the Quetzales Sajoma basketball club in Mexico that uses the quetzal (Tragonidaespp.), an emblematic bird from the Maya and Aztec cultures. Animal symbols also communicate club values such as unity or solidarity – for example, the supporter group of LOU Rugby is called “La Meute” (“The Pack”). Nicknames can also highlight a club’s colours, as with the “Zebras,” nickname of Juventus FC, whose jerseys are famously black and white.

LOU Rugby

Finally, many emblems directly reference the local environment – such as the Parramatta Eels, named after the Sydney suburb, whose Aboriginal name means “place where eels live”.

The Wild League: Sports clubs as allies to wildlife

The sports sector has grown increasingly aware of climate-related issues, both those related to sports practice and sporting events. Biodiversity has not yet received the same attention. The study also shows that 27% of the animal species used in sports identities face risks of extinction in the near or medium term. This concerns 59% of professional teams. Six species are endangered or critically endangered, according to the IUCN: the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), African elephant (Loxodonta africana), Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), tiger, and Puerto Rican blackbird (Agelaius xanthomus). Lions and leopards – two of the most represented species – are classified as vulnerable.

Moreover, 64% of teams have an emblem featuring a species whose wild population is declining, and 18 teams use species for which no population trend is known. If this seems surprising, think again: the polar bear (Ursus maritimus), orca (Orcinus orca), and European wildcat (Felis silvestris) are among these poorly understood species.

Under these circumstances, can sport help promote biodiversity conservation in an inspiring way? Indeed, iconic clubs and athletes, whose identities are based on often charismatic but endangered species, bring together millions of enthusiasts.

Another study by the same research team presents a model aligning the interests of clubs, commercial partners, supporter communities, and biodiversity advocates around the central figure of animal sports emblems.

Playing as a team for a common goal: Protecting biodiversity

The Wild League project, which builds upon these recent scientific publications, aims to implement this model with the support of clubs (professional and amateur) and their communities, in order to involve as many stakeholders as possible (teams, partners, supporters) in supporting ecological research and biodiversity conservation.

These commitments are win-win: for clubs, it is an opportunity to reach new audiences and mobilise supporters around strong values. Sponsors, for their part, can associate their brands with a universal cause. By scaling up, a professional league, if it mobilised all its teams, could play a key role in raising awareness of biodiversity.

Deutsche Eishockey Liga/X.com

Many mechanisms could help implement such a model, involving teams, partners, and supporters in changes to individual and institutional behaviour. Teams from different sports that share the same emblem could pool resources to create coalitions for the protection of the species and its ecosystem.

Conversely, an entire professional league with numerous teams represented by different animals could raise awareness by embracing biodiversity as a collective theme. For example, Germany’s top ice hockey league (DEL) includes 15 teams, 13 of which feature highly charismatic animals: every week, panthers face polar bears, penguins battle tigers, and sharks challenge grizzlies! These emblems provide a unique opportunity to raise awareness of the Earth’s biological diversity.

Some well known but taxonomically vague nicknames – such as “Crabs,” “Bats,” or “Bees” – conceal immense species diversity: more than 1,400 species of freshwater crabs, as many bat species (representing one in five mammal species), and over 20,000 species of bees exist worldwide.

Auckland Tuatara

Finally, more than 80 professional teams have a unique one-to-one association with a species. The Auckland Tuatara basketball team, for instance, is the only one to feature the Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), a reptile found only in New Zealand. These exclusive connections create ideal opportunities to foster a sense of responsibility between a species and its team.

Auckland Tuatara

Sport is above all an entertainment industry, offering powerful emotional experiences rooted in strong values. The animal emblems of sports clubs can help reignite a passion for the natural world and engage sporting communities in its protection and in broader biodiversity conservation – so that the roar of lions does not become a distant memory, and so that the statues proudly standing before our stadiums regain their colour and meaning.

The post “Sports clubs as new champions of biodiversity” by Ugo Arbieu, Chercheur postdoctoral, Université Paris-Saclay was published on 12/22/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply