We all scream for ice-cream, especially as temperatures soar in the summer. Ancient civilisations had the same desire for a cold, sweet treat to cope with heat waves.

There are plenty of contenders claiming credit for the first frozen desserts, from Italy and France in the 17th century to China in the first century.

But before you can make ice-cream, you need a reliable source of ice. The technology to make and store ice was originally developed in Persia (modern-day Iran) in 550 BCE.

Ancient ice makers

These ancient Persians built large stone beehive shaped structures called yakhchal (“ice pit”). They were constructed in the desert, with deep, insulated subterranean storage, making it possible to store ice all year.

High domes pulled hot air up and out, and wind catchers funnelled cooler air into the base. The yakhchal was not just an ancient ice house, it was also an ice maker.

Jeanne Menj/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Canals filled shallow ponds, shaded from the sun, with fresh water during the winter. Overnight temperatures dropped, and in the dry desert air the water would cool through evaporation.

Some yakhchals have survived centuries of desert erosion, and are found across Iran in areas where it is cold enough to produce ice in the winter, or close to mountains where ice could be harvested.

A study of one 400-year-old yakhchal, still standing in Meybod, estimated its annual production at 50 cubic metres – about 3 million ice cubes.

Early frozen desserts

Stored ice was used to make frozen desserts such as fruit sorbets, sharbats, and faloudeh (frozen rosewater and vermicelli noodles) sweetened with honey syrup.

After the Arab conquest of Persia circa 650 CE, the Persian method for ice production and storage spread across the Middle East.

The new technology was used to freeze milk and sugar mixed with salep flour (powdered orchid root) and mastic (dried sap from an evergreen bush) to make stretchy forms of ice-cream in Syria, like booza and bastani, in Persia.

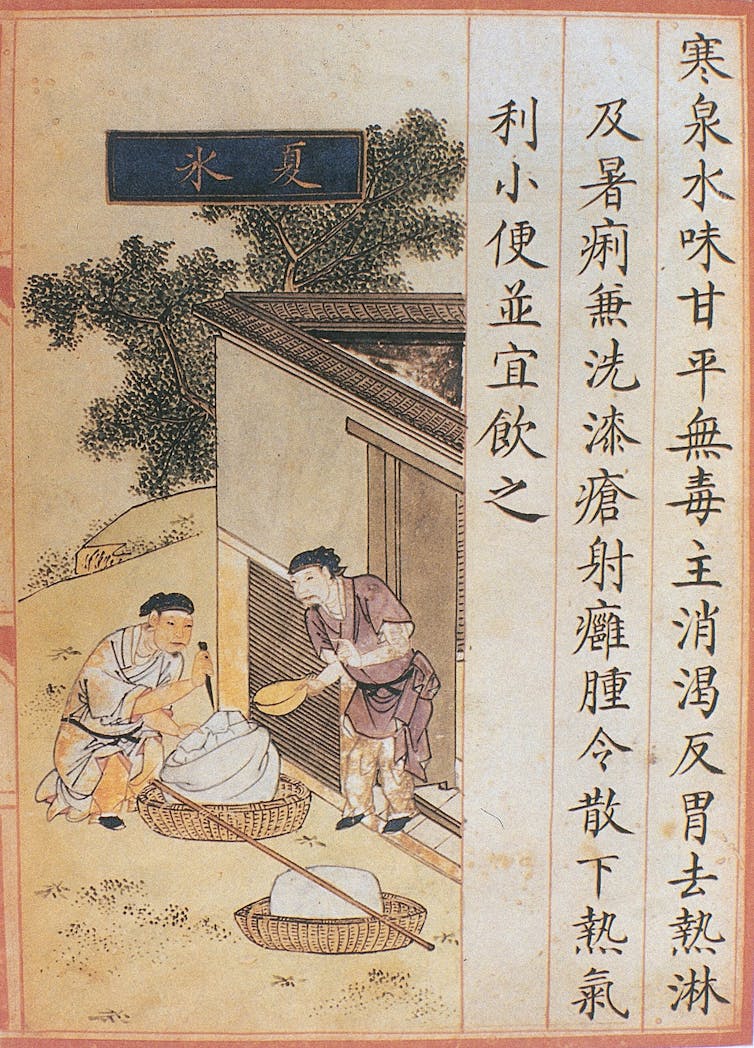

Wellcome Collections

A frozen dessert, sushan, (literally “crispy mountain”) was also developed in China in this period, during the Tang Dynasty (618–907). Goat’s milk curd was melted, strained and poured into metal moulds shaped like mountains.

The final texture was described by poet Wang Lingran as being somewhere between a liquid and a solid, melting in his mouth.

Discovering the science of freezing

Freezing techniques changed when a popular book on “natural magic” – meaning everything from natural science to astrology and alchemy – was first published by Giambattista della Porta in Naples in 1558.

Magia Naturalis included instructions on how saltpetre (potassium nitrate) could be added to ice to rapidly chill wine for summer feasts:

cast snow into a wooden vessel, and strew into it Salt-peter, powdred, or the cleansing of Salt-peter, called vulgarly Salazzo. Turn the Vial in the snow, and it will congeal by degrees.

This method meant it was much easier to freeze liquids, because potassium nitrate dissolved in water draws heat out of the surrounding environment.

Yale Center for British Art

Experiments in the 17th century revealed a similar reaction occurs with mixture of ordinary salt, water and ice. Smaller quantities of stored ice could now be used to freeze and chill mixtures to create frozen desserts on demand.

This technology was combined with supplies of cheaper sugar sourced from European plantations in the Caribbean. Sugar is an important element of frozen desserts because it keeps mixtures from freezing into impenetrable ice blocks.

France v Italy in the claim for first ice-cream

Two claims for the “first” ice-cream recipes emerge at almost the same time in France and Italy in the 1690s.

Earlier attempts produced granular, slushy confections. Recipes that produced results we would recognise today were introduced by men who managed households for noble patrons.

Alberto Latini, working for Cardinal Barberini (nephew of Pope Urban VIII), had access to expensive and novel ingredients, like chocolate and tomatoes. His recipe for a new “milk sorbet” aligned with the cutting edge cooking methods in the 1694 edition of his book, Lo Scalco alla Moderna (The Modern Steward).

This recipe used milk, sugar, water and candied fruits, and is considered a precursor to Italian gelato.

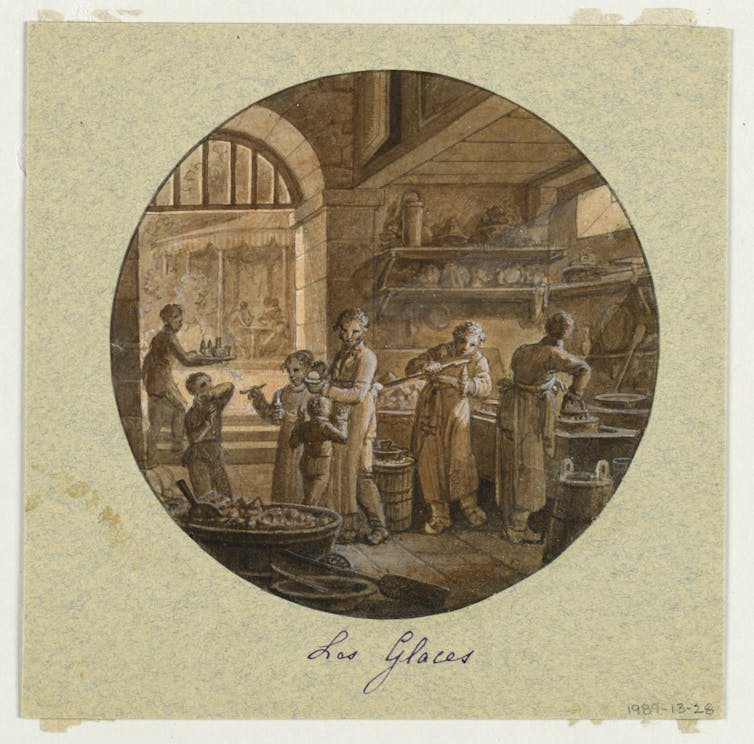

Cooper Hewitt Museum

The other contender for first ice-cream is Nicolas Audiger, who had worked for Jean-Baptiste Colbert, chief minister to Louis XIV, who helped prepare feasts at Versailles.

He published a handbook on running noble households, La maison réglée, in 1692 with numerous recipes for fruit sorbets, and one for ice-cream sweetened with sugar and flavoured with orange blossom water.

While both claims have merit, Audiger’s recipe included detailed descriptions of the techniques for stirring and scraping to ensuring a better texture and even distribution of sugar throughout the mixture. He wrote his volume after spending 18 months in Italy, so he probably learned Italian techniques and refined them, leading to the creamy delights we now enjoy.

The ice-cream paradox?

In the northeastern United States, the original Ben and Jerry’s ice-cream factory in Vermont used to run a promotion where prices changed as the weather got colder. As temperatures dropped below freezing, ice-cream cones got cheaper.

State Library of South Australia

This might lead you to think that people in the hottest climates eat more ice-cream, but the highest per capita consumption in the world is in Aotearoa New Zealand, followed by the US and Australia. The next four countries are famous for being cold: Finland, Sweden, Canada and Denmark.

Maybe the answer to this apparent paradox is that when it is hot you need ice-cream to cool you down, and when you are cold and miserable you need it to cheer you up.

The post “the 2,500-year history of ice-cream” by Garritt C. Van Dyk, Senior Lecturer in History, University of Waikato was published on 12/31/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply