Warning: this article contains spoilers for the novel and film Frankenstein.

Watching Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein after my return from the 2025 Arctic Circle Assembly (ACA) in Reykjavik, I was intrigued by his adaptation of the Arctic setting of Mary Shelley’s novel.

The novel follows Dr Victor Frankenstein (played by Oscar Isaac in the film), a scientist who creates a living being from dead body parts, only to abandon him after the consequences of his experiment horrify him.

Rejected and lonely, the Creature (played by Jacob Elordi) seeks revenge on Victor. The novel’s story is framed by letters from an explorer, Robert Walton (changed to Danish Captain Anderson by Lars Mikkelsen in the film), who encounters Victor in the Arctic as he pursues the Creature.

WikiCommons

Del Toro’s film presents the Arctic of the 1800s as a barren wasteland. While at the ACA, I asked Janne Oula Näkkäläjärvi, development manager at the Sámi Education Institute about this depiction. He said: “It feels sad and absurd. The Arctic is not empty – it is the home of many Indigenous peoples, including the Sámi, who have thrived here in harmony with nature for thousands of years.”

His position reflects the ongoing project to rewrite Arctic history through the perspective of Indigenous Arctic peoples. In this sense, Del Toro’s film, while faithful to the novel in many other ways, arguably misses an opportunity to deliver the anti-colonial political message embedded in Shelley’s work.

Shelley’s story implicitly draws attention to the overlaps between Frankenstein’s unethical experiments with human life and Walton’s “ardent curiosity” and desire to “tread a land never before imprinted by the foot of man”.

Although no Inuit characters feature in her novel, Shelley’s anti-imperial stance emerges throughout, and exposes Walton’s colonial us-versus-them mindset: “He was not, as the other traveller seemed to be, a savage inhabitant of some undiscovered island, but an European,” he says, when he sees the sledge carrying Frankenstein and the Creature.

Frankenstein was first published in 1818 and again with revisions in 1831. This was a time of growing British interest in exploring and claiming Arctic regions. This surge in exploration began in the early 1800s, when Sir John Barrow was appointed Second Secretary to the Admiralty. Under his leadership, Britain launched more Arctic expeditions than ever before, driven by both scientific curiosity and colonial ambition.

In 1818 Barrow’s first book on his Arctic explorations, A Chronological History of Voyages into the Arctic, was published by John Murray. That same year, the Admiralty increased its investment in Arctic exploration. In particular, the search for the North-West Passage (a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic) intensified.

Mary Shelley read many of the Arctic travel accounts published by John Murray, and they likely inspired the Arctic sections of Frankenstein. Shelley even sent her manuscript to John Murray, who rejected it.

Del Toro’s Arctic

Shelley’s novel is set in the 18th century, but Del Toro’s film is set in 1857, when British imperialist confidence was beginning to suffer significant blows. This was the year, for instance, of the Indian mutiny against British rule, while, in 1856, tension between Britain and China led to the second opium war.

The decline of the British Empire was also dramatically reflected in Arctic exploration disasters. Many vessels failed to deliver their missions and returned home having suffered considerable losses.

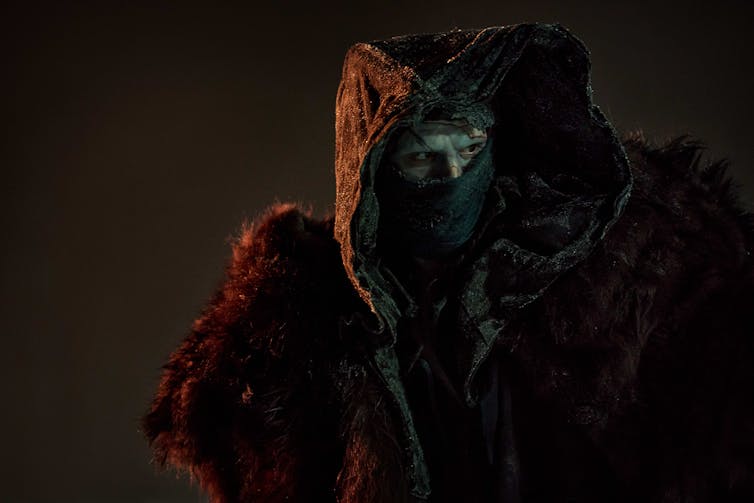

Ken Woroner/Netflix

The doomed 1845-46 expedition of Sir John Franklyn’s HMS Erebus and HMS Terror was the most notable of such Arctic disasters. The ships never returned (the wrecks were only found in 2014 and 2016) and evidence from Inuit accounts of the mission suggested the crew had turned to cannibalism.

The controversial claim, shared initially by Orcadian explorer John Rae, and dismissed because of “the very loose and unreliable nature of the Esquimaux [sic] representations” by Charles Dickens, firmly put the Inuit in the European map of the Arctic, and, simultaneously, exposed the persistent racist bias of Imperial ideology.

In line with these Victorian views of the Arctic, Del Toro’s Frankenstein depicts the Arctic’s elusive barrenness simultaneously as a force hostile to the explorers from the south and a blank canvas for them to chart, control and ultimately, exploit.

His vision of the Arctic owes more to the sublime wilderness of 19th-century paintings such as Edwin Landseer’s Man Proposes, God Disposes (1864), than more recent representations including the 1973 Marvel comic adaptation of The Monster of Frankenstein, or the first television series of The Terror (2018).

The Terror retold the story of the Franklyn disaster based on the eponymous 2009 novel by Dan Simmons. While it was not filmed in the Arctic, the series was praised by critics for its inclusive script and casting, which included Inuuk actor Nive Nielsen.

Royal Holloway, University of London

At the end of Frankenstein, the Creature spectacularly sets the Danish boat free to sail on a much-awaited southbound journey. His own lonely figure, significantly, is left to wander the Arctic barrenness in perpetuity.

Perhaps this apparently conservative emphasis on Arctic blankness is intentionally critical of the multiple forms of colonial oppression exposed by Shelley’s novel. There is, after all, an interesting parallel between Del Toro’s Arctic, with its limitless white expanse marked only by the traces of European blood, and the body of the Creature, his pale skin crudely scarred by the scientist’s stitches.

Both the Arctic and the Creature are exceptionally “undead” – simultaneously lifeless and supernaturally alive. Both are slates wiped blank, so that new master-slave stories can be written upon them.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The post “The Arctic in Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein reveals more about empire than about monsters” by Monica Germanà, Reader in Gothic and Contemporary Studies, University of Westminster was published on 10/23/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply