It’s hard to believe Steven Spielberg was just 27 when he directed Jaws. Before that he’d mostly worked in television, helming episodes of detective show Columbo and the acclaimed TV movie Duel. He’d made just one theatrical feature, The Sugarland Express.

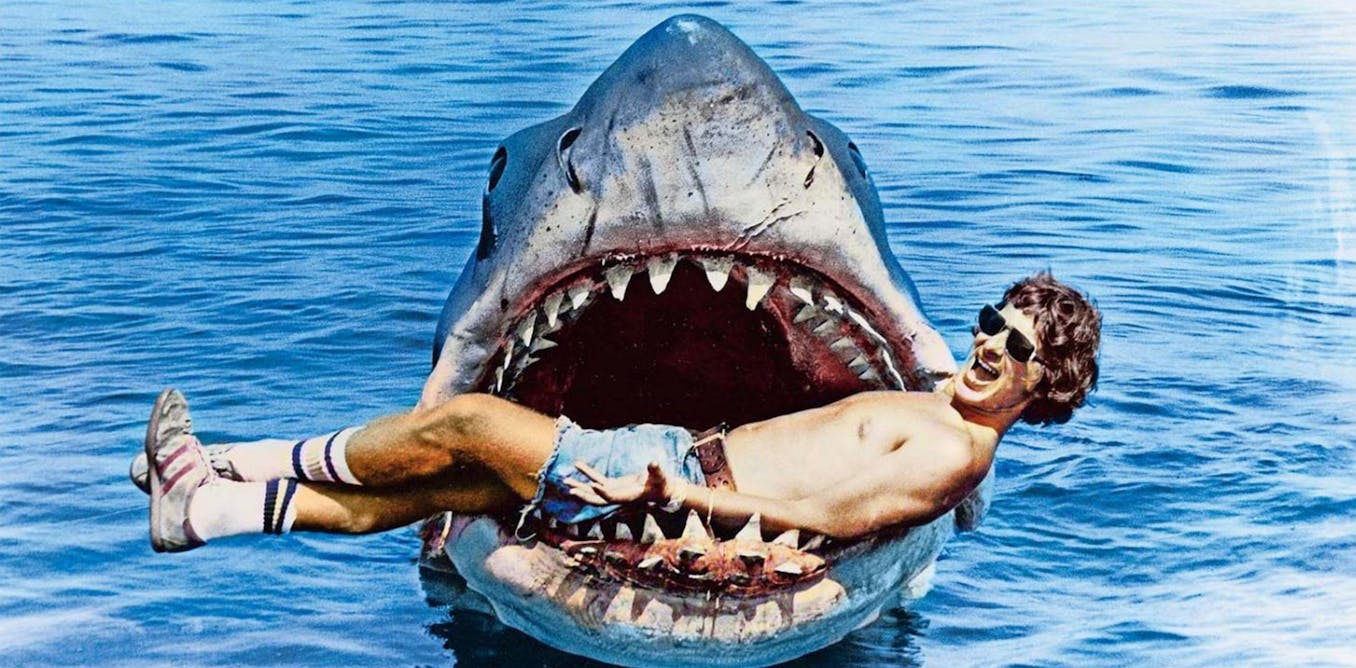

Then came Jaws, a technically ambitious shoot set on open water with a mechanical shark that barely worked. But the result was a record-breaking blockbuster that redefined what Hollywood could be.

Adapted from Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel, the film almost didn’t happen. When Spielberg first read it he said he found himself rooting for the shark because the human characters were so unlikable.

What followed was a series of creative rewrites and re-castings that gave Jaws its distinctive personality and enduring power.

Spielberg brought in Howard Sackler, a writer and scuba diver, to work on the script. Sackler left early without a screen credit. The director then turned to actor Carl Gottlieb, originally hired to play a toadying local newspaper editor, to redraft the script. Screenwriter and director John Milius, a second world war expert, also contributed.

John Williams added what became an iconic musical score. Its simple two-note motif created suspense and became one of the most recognisable cinematic themes of all time.

As a researcher of Jewishness in popular culture, I argue that many of these creatives brought a Jewish sensibility that lurked beneath the surface of the film.

Spielberg took Benchley’s bitter, cynical and pessimistic novel and gave it a more hopeful vibe. He even humanised the shark, giving it the name Bruce after his lawyer, Bruce Ramer, a powerful and influential Los Angeles attorney specialising in entertainment law, also Jewish.

That choice layers in unexpected meanings, from the “loan shark” stereotype to echoes of Shakespeare’s Shylock from The Merchant of Venice.

Hooper v Quint

Spielberg cast Jewish actor Richard Dreyfuss as Matt Hooper, the young ichthyologist and oceanographer. Against him stood Robert Shaw as Quint, the grizzled boat captain, who is a sexist, misogynistic, racist macho drunk. Hooper is everything Quint is not. Making up the triumvirate is Roy Scheider as police captain Martin Brody. Together, the three seek to capture and kill the shark that is menacing the town of Amity.

The casting of Dreyfuss as Hooper, whom Spielberg called “my alter ego”, significantly changed the character and the tone of the film. Together, Dreyfuss, Gottlieb and Spielberg fleshed out Hooper’s part, making him much more sympathetic than in the novel. He became a “nebbishy novice on a swift learning curve”.

For Spielberg, Hooper “represents the underdog in all of us”. Benchley, however, was less than impressed, describing him as “an insufferable, pedantic little schmuck”. It’s telling that Benchley used a Yiddish epithet to describe Hooper as if recognising his underlying Jewishness.

Together, Spielberg and Gottlieb used Hooper as a mouthpiece to voice a social perspective. Brody wishes to close the beaches but is prevented from doing so by the mayor and the town council because Amity needs the business. The mayor puts commerce before human life. In a shift from Benchley’s novel where the pressure to keep the beaches open comes from shadowy pseudo-Mafia figures in the background, Spielberg placed the blame firmly on Amity’s merchants and civic representatives.

Throughout, Spielberg undermines the dominant masculinity of the screen action hero of the 1970s. This was an era dominated by men like Burt Reynolds, Clint Eastwood and Gene Hackman. Nerdy Hooper outlives Quint, who becomes the shark’s fifth victim (hence his name, which is Latin for five or fifth). To show his contempt for Quint, Spielberg gives him a particularly gruesome death.

And because Spielberg identified with the shark, we see things from its subjective perspective. This was also dictated by pragmatic concerns as the mechanical shark kept breaking down. Shooting the killings from the shark’s point of view was a cinematic device borrowed from A Study in Terror (1965), a British thriller about Jack the Ripper.

Jaws was a box office smash, breaking records previously set by The Godfather and The Exorcist and becoming the first film to reach the US$100 million (£74.5 million) mark at the American box office.

Read more:

Jaws at 50: a cinematic masterpiece – and an incredible piece of propaganda

Before Jaws, studios typically released major films in the autumn and winter, leaving the summer for lower-quality movies. Jaws proved that it could be a prime time for big-budget, high-profile releases, leading to the current dominance of tentpole films during the summer season.

It pioneered the strategy of opening a film in a wide release, rather than a gradual rollout. This helped it break box office records and redefine Hollywood’s practices. It was something that people got excited about, planned for and lined up for tickets in advance.

Why has the film lasted?

Half a century on, Jaws still has the power to shock. When I took my kids to see the 3D re-release, we all jumped during the scene when the decapitated head bobbed out of the sunken boat – even though I knew it was coming.

Another reason why the film has lasted is the shark itself. It’s a primal, prehistoric creature that taps into our deepest fears. Quint calls it a thing with “lifeless eyes, black eyes, like a doll’s eyes”. It’s a chilling line.

But the film also works as allegory. The shark is a floating (or swimming) signifier, open to interpretation. Amity, the town it terrorises, is all white picket fences and small-town harmony. The shark’s arrival punctures that illusion.

There’s also a political undercurrent. Hooper becomes the conscience of the film, voicing the dangers of civic denial and inaction.

And in the end, Jaws isn’t just about a shark. It’s about masculinity, morality and capitalism. It’s about the stories we tell ourselves to feel safe. That’s why it endures. That, and one of the most iconic scores in cinema history – John Williams’ two-note motif that still makes swimmers glance nervously at the waterline to this day.

The post “the Jewish sensibility that shaped Spielberg’s blockbuster and transformed cinema” by Nathan Abrams, Professor of Film Studies, Bangor University was published on 06/19/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply