As the seasons turn and the nights draw in, the countryside of the British Isles seems alive with omens: an owl’s screech, or a bat above the hedgerows.

For centuries, such creatures were cast as messengers of fate, straddling the boundary between the natural and the supernatural. Yet today, the omens these animals bring are no longer warnings of ghosts or witchcraft, but of something far more tangible: their own survival.

The very species that once haunted our imagination and foretold ill-fated futures are now haunted by habitat loss, climate change and pressure from urbanisation. In the stories of these creatures, we glimpse both our fear of the wild past and our responsibility for the future. Now is the time to revisit some of Britain’s iconic “omen animals”, tracing their folklore and asking what their fate tells us about our shared environment.

Hedgehogs

Hedgehogs, though voted Britain’s favourite mammal, were previously deemed to be milk thieves.

Quirk Books

A widespread folkloric belief of the early modern period, likely exacerbated by the European witch hunts, was that witches would transform into hedgehogs to steal milk from cows’ udders. This belief was so prevalent that a campaign to hunt and eradicate hedgehogs was backed by English parliament, with a bounty of a tuppence placed on the head of each hog.

Though their public image has recovered in recent years, hedgehogs are now classed as “vulnerable” to extinction in the UK. Their key threats are linked with habitat loss and fragmentation. Their natural prey, insects and invertebrates, are also in decline due to increased use of pesticides.

Declines in hedgehogs have been particularly steep in rural habitats, with populations reduced by 30–75% since 2000. Conservation priorities focus on restoring lost habitats for hedgehogs and understanding how best to protect them.

Adders

As the only venomous snake in the UK, it is unsurprising that the adder would attract some negative publicity over the years. The species is increasingly a conservation concern and now locally extinct across much of England due to habitat loss.

An “adder’s fork” was a spell ingredient listed by the witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606). He invoked them too in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1600) as a way for one character to accuse another of treachery and deceit.

British Library Harley MS

Even more sinister, finding an adder on your doorstep was considered a death omen. It is now unlikely for your threshold to be crossed by an adder, as they are now mostly found in small, isolated populations. Even they could be lost by 2032.

Conservation efforts are focusing on the creation, restoration and management of suitable grassland, but are not currently widely implemented. Increasing public awareness and appreciation of the species is a key goal for adder preservation.

Wildcats

Once widespread across Britain, wildcats are now considered our most endangered animal species. They have a long reputation in Scottish folklore for being untameable, serving as the namesake of the Pictish province of Cataibh when it was formed in 800BC. They were often adopted as symbolic emblems or mascots in early clan lore due to their fierce fighting spirit. Their ominous cry is thought to have inspired ghost stories across the ages.

British Library, Royal 12 C XIX

Deforestation and persecution, especially by Victorian gamekeepers, eradicated wildcats from England, Wales and much of Scotland. In 2019, experts concluded that breeding with feral domestic cats has compromised their genetic integrity and that the remnant populations are too small, isolated and genetically degraded to have a long-term future.

But some hope does remain for the wildcat. Saving Wildcats, a European partnership project dedicated to wildcat conservation, is leading efforts to breed the species in captivity. As of 2023, a number of wildcats have been into Scotland’s Cairngorm National Park.

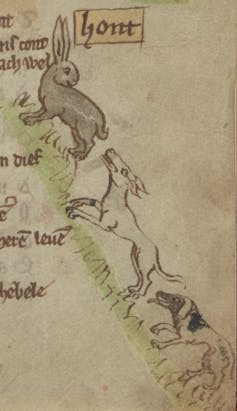

Mountain hares

The mountain hare is the UK’s only native member of the hare and rabbit family. Once widespread across Britain, mountain hares are now confined to upland regions of Scotland and the Peak District.

The Medieval Bestiary

Hares have a long history of superstitious and folkloric attachments. They were seen as shape-shifters, or familiars of witches, which would bring doom and misfortune to any person unfortunate enough to have their path crossed. Their shape-shifting abilities were referenced in The Mabinogion, a collection of Welsh stories compiled in the 12th and 13th centuries, across Celtic folklore before. Numerous regional hare-witches were referenced across England.

While fear of wronging a witch historically offered hares some protection, they have faced decline and range reduction from competition with brown hares, hunting pressures and land use change. Recent surveys suggest a 70% crash in the Peak District population over just seven years. Under current rates of decline, the mountain hare will become extinct from the region within five years.

Nightjars

Summer visitors to the UK, nightjars were once thought to drink milk from goats and in doing so poison them and cause their udders to wither away. These birds were also said to snatch up lost souls wandering between worlds with their unearthly call.

The Medieval Bestiary

Nightjars suffered a catastrophic population decline in excess of 50% and range contraction of around 51% during the latter half of the 20th century. However, surveys conducted in 1992 and 2004 saw welcome population increases of 50% and 36% respectively. Nightjar were recorded making use of new clear-felled and young conifer plantations and benefiting from long-term habitat management projects in their southern strongholds. Although recent recoveries offer hope, nightjars have reclaimed only a fraction of their former range – around 18%.

These species, and far more besides, have been instrumental in the stories people have woven across time. So the next time you hear the screech of an owl outside your bedroom window or glimpse the wings of a bat flapping over your garden, pause to think about the omens of our wild country – and how their stories might yet continue.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The post “The medieval folklore of Britain’s endangered wildlife ‘omens’ – from hedgehogs to nightjars” by Jessica Lloyd May, PhD Candidate in History, University of Nottingham was published on 10/14/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply