If asked to describe what sets a cognitively complex species like humans apart from others, many would list specific behaviors, such as telling stories, creating art, planning for the future, or navigating complex social structures. Given that, you might expect that neuroscientists attempting to understand the advanced brain would study it in action, as a person or animal moves through the world.

For much of its history, though, neuroscience has done the opposite.

“When I was a graduate student, neuroscience was almost entirely about isolating specific circuits to test how the brain controls your senses and movement,” says Dr. Earl K. Miller, the Picower Professor of Neuroscience at MIT. “You’d show an animal a stimulus, observe how it responded, and record which neurons fired.” This research defined foundational principles of the field, but according to Miller, when you study the brain at this level, “you’re really only looking at its edges.”

“We know surprisingly little about how the brain manages more complex cognitive behaviors, like making a decision or socializing,” says Felipe Parodi, a PhD candidate in neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania, co-advised by professors Michael Platt and Konrad Kording. “Studying primates and humans in the confines of the laboratory, where they can’t interact freely, won’t tell you what the brain is doing when a primate forms a bond, infers an intention, cooperates, or manages conflict.”

Classical neuroscience doesn’t fully capture how the brain operates in more natural, real-world contexts.

Parodi isn’t the first to identify this problem. Researchers have long argued that we need to measure brain activity as animals behave freely, but this type of research has only recently become possible thanks to advances in the tech needed to study freely moving animals and in the computational methods used to analyze the massive datasets created through these studies.

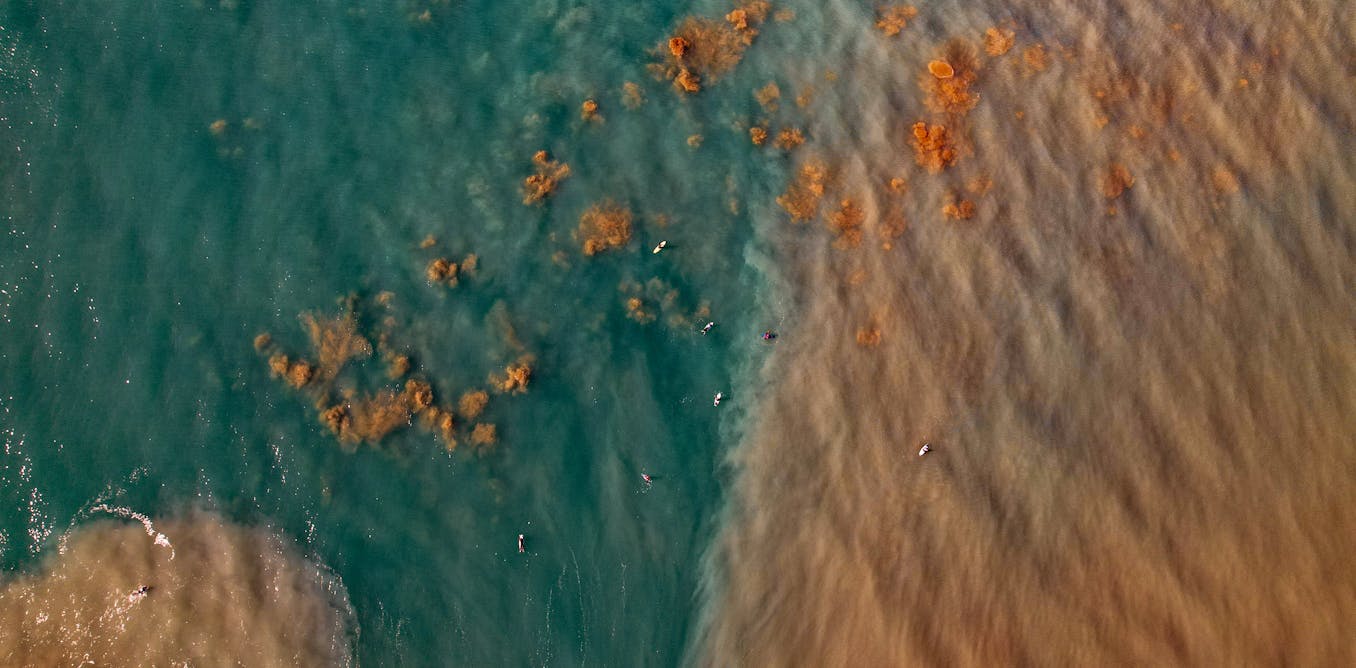

In 2025, Parodi co-authored a synthesis on primate neuroethology, an emerging field that blends neuroscience and ethology — the study of an animal’s natural behavior — to track brain activity under the messy, real-world conditions that brains like our own evolved to handle. Despite being in its infancy, the field is already proving its worth. Early studies show that freely moving primates display richer neural dynamics than restrained ones, for example, even when they are performing very similar tasks.

That doesn’t mean results from classical neuroscience are wrong, but it does suggest they don’t fully capture how the brain operates in more natural, real-world contexts. For that, we may need a paradigm shift.

The limits of classical neuroscience and ethology

Neuroscientists have been studying more cognition-based questions — like how the brain recognizes patterns, remembers information, or learns rules to get a reward — for some time now. “Studying tasks that tapped into real cognition opened up whole sets of neural properties you simply don’t see in basic sensory tasks,” says Miller. But the experimental setup rarely changed, and the strengths of classical neuroscience — precision and control — limited the reach of these studies.

Ethology and related fields such as behavioral ecology have the opposite strengths and weaknesses. Primatologists can observe and track natural behavior in extraordinary detail and develop ecological theories about how certain behaviors impact survival. While classical neuroscience might reveal how the brain creates behavior, ethology reveals why a behavior might matter.

One case offers a clear example of the kinds of questions that neither primate ethology nor neuroscience can answer on its own.

In 2017, Hurricane Maria devastated Cayo Santiago, an island where researchers had spent decades tracking a population of rhesus macaques. The storm tore down the trees that once provided shade, pushing daily heat to punishing levels. Before the hurricane, the macaques kept tight, selective social circles and didn’t tolerate being in close proximity to monkeys outside of their social circle. Afterward, though, many monkeys shifted how they interacted. They tolerated one another more, spent more time near others, and formed broader social networks.

The monkeys who changed their behavior in response to the new conditions had a higher chance of surviving, whereas those who didn’t were much more likely to be exposed to extreme heat. Put another way, behavioral flexibility became a matter of life or death.

Ethologists could track the shift in behavior, but they couldn’t see how the brain registered these new pressures or how it recalculated the costs and benefits of tolerance in a new environment. Why did some animals adapt faster? What cognitive processes made a primate decide to be tolerant, rather than aggressive?

These are the kinds of questions that traditional lab neuroscience can’t address and that observational ethology doesn’t attempt to answer. Neuroethology aims to bridge that gap.

Studying the brain in motion

The key to neuroethology is studying animals as they perform “natural behaviors.” Taken literally, though, the term gets slippery fast. If an animal does something, isn’t it natural by definition? Everything we do is bounded by our biology — I can’t fly or echolocate no matter how hard I try.

In practice, researchers use “natural” to mean a behavior a species performs routinely in its normal environment. For primates, that includes foraging, grooming, climbing, and navigating social hierarchies. Memorizing arbitrary visual sequences or responding to abstract cues on a touchscreen are behaviors that fall outside the natural range.

Is doomscrolling on Instagram a natural behavior for humans? Miller argues that the line is fuzzy: “People ask me, ‘Isn’t it unnatural to have a person sit in front of a computer for months learning a task?’ Sure. But humans do tons of arbitrary things, like play an instrument for years or learn abstract rules, and our brains handle that just fine. Whether something is ‘unnatural’ depends on what you’re trying to study.”

Many neuroethology studies blend the experimental control of classical neuroscience with the behavioral richness of a more naturalistic environment.

And that is the point for neuroethologists. The distinction helps shape the questions they can ask and what types of conclusions they can make. For them, what matters is not only what the animal is doing but where and how it is doing it. Is the behavior one that the species typically performs? Does the setting, whether a lab, a semi-natural enclosure, or the wild, allow the behavior to unfold? Is the animal free to move?

A primate foraging among groupmates in a large enclosure, for example, fits well within a neuroethological approach, even if the setting is not fully wild. A primate tapping a screen to “pretend” to forage for an arbitrary reward, like a sugar pellet, does not. The first can reveal how the brain works in real foraging situations. The second can be valuable, but only to answer different questions.

Many studies take the middle ground, blending the experimental control of classical neuroscience with the behavioral richness of a more naturalistic environment. This “stepping-stone” approach doesn’t recreate the wild, but it does relax the most restrictive conditions and allow animals to move and interact more freely. “You don’t need to jump straight into the wild, and right now, we couldn’t even if we wanted to,” says Parodi.

Some research groups place primates in immersive virtual reality scenes that let them carry out tasks similar to those they would complete in the wild, such as searching for food or moving through a three-dimensional space. These setups produce brain activity that is far richer and more varied than what appears when the animals are limited to standard lab routines meant to mimic those same behaviors. Still, most primate neuroethology research happens in a pen or enclosure. These settings let primates roam more freely while minimizing confounding variables that would always be present in the wild, such as other animals.

The social lives of primates

According to Parodi, a neuroethological study is most likely to yield meaningful insights when it focuses on a specialized behavior that an animal is exceptionally good at and that is very difficult, or impossible, to study under artificial conditions. Social activity is particularly rich for this kind of research. “Social interaction is central to primate life,” says Parodi. “You don’t get far as a primate unless your brain can track and navigate complex relationships.”

Miller agrees: “Social interactions are where naturalistic work has made the most progress and where it has the most potential to contribute to the field. You can’t study these behaviors in a stripped-down lab setting.”

One active area of research is how primates manage reciprocal exchanges, those subtle, give-and-take interactions that are fundamental to both human and nonhuman primate life. For a 2024 study, Parodi and his colleagues tracked the brain activity of a freely moving group of macaques while they were grooming one another. The results revealed a set of neural populations that maintained a “social ledger” of who had groomed whom, how often, and for how long. The internal accounting didn’t just store past interactions, either — it also forecasted likely future returns and may have influenced the formation of alliances in these communal societies.

“Primatologists already had a hunch that monkeys kept track of these types of interactions,” says Parodi. “The discovery is where in the brain it happens and how … When I, as a macaque monkey, interact with my mother or my father, what happens? And what happens when I’m no longer a neurotypical primate? If we understand how these circuits work, we can understand why and where they go wrong.”

While most neuroethological studies focus on social behaviors, some have explored how the brain handles complex decision-making, communication, memory formation, and more. A recent study that tracked how freely moving rhesus macaques make foraging decisions, for example, found that the monkeys’ neural signals were processing competing variables simultaneously to make decisions, including their physical environment, the presence of other primates, and trade-offs between trying something new and sticking to the usual choice.

Neuroethology’s growing pains

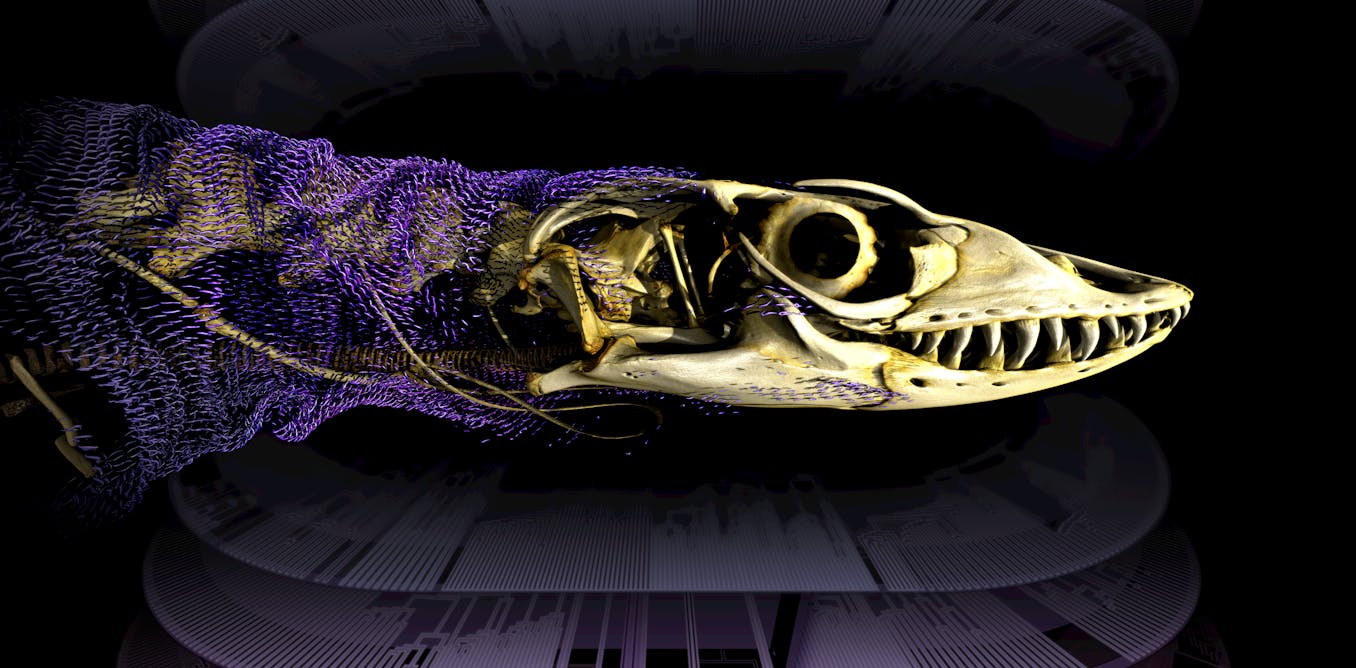

Studying complex behavior in real-world environments brings real challenges. For most of neuroscience’s history, the field simply lacked the tools to monitor brain activity in freely moving animals, but today, researchers can equip primates with lightweight neurologgers that track brain signals without restricting movement. Importantly, the primates quickly habituate to the devices and return to their typical behavior.

Still, these tools need to be even more powerful and lightweight to push the field forward. To that end, researchers are now working on devices that can record high-quality signals from thousands of neurons across multiple brain regions without restricting an animal’s movement.

Real behavior is as complex as the brain gets.

Earl K. Miller

The biggest challenge, however, may not be technological, but computational. Neuroethology deliberately embraces the behavioral variability that classical neuroscience often controls away, and that variability is hard to analyze. “Traditional neuroscience mostly communicates averages: how a neuron fires on average to a stimulus, or how it responds on average across trials,” says Parodi. The trouble, he explains, is that real behavior isn’t an average: “Every human behavior is a distribution. To be ‘neurotypical’ is a spectrum, not one central value.”

That variability grows more daunting as the setting grows more natural. “Real behavior is as complex as the brain gets,” says Miller. “There are countless variables that can influence a single action, and today’s computational models can’t fully separate the signal from the noise. They’re not going to handle that anytime soon.”

The problem can surface in something as simple as a decision to approach or avoid another animal. That one choice could be shaped by hunger, prior conflict, stress, status, the presence of others, or even the weather. The neural signal the scientist captured is real, but how do they know what influenced it?

That tension lies at the heart of neuroethology. While modeling tools are improving alongside the technology, they aren’t yet advanced enough to eliminate uncertainty. “We are conducting rigorous experiments, but I’m not afraid to admit that you do have to sacrifice a bit of statistical control to study this natural variability,” says Parodi.

What comes next?

The field of neuroethology is still in its infancy, but Parodi seems excited about its potential for growth: “In 10 years, we’ll probably look back and say we didn’t know what we were doing. Or maybe even in one year.”

He is especially interested in scaling this work to full group dynamics. “I’d love to record from multiple primates at once,” he says. “I’m especially curious about how individuals change in social groups. What happens when one monkey is surrounded by five others? Do they act differently? Do they have a preferred partner, like a best friend? Does the brain reflect that?”

The field has yet to extend into truly wild environments, relying instead on semi-natural settings, like enclosures, but that will soon change. One of the first wild neuroethology studies will launch on Cayo Santiago, the same island where researchers observed shifts in monkey social behavior after Hurricane Maria. This time, the goal is even more ambitious: to outfit individual primates with neurologgers and follow them continuously for a full year. “We expect that study to happen in the next five years, which is so, so exciting,” Parodi says through a grin.

This kind of long-term, real-world neural tracking could lead to new ways of understanding, and eventually treating, conditions like autism or schizophrenia by identifying what “typical” social processing looks like in complex settings. It could also shape how we build socially intelligent AI. “If we understand what it means to interact appropriately and inappropriately, we can train digital agents to do the same,” says Parodi.

Ultimately, though, the complex field of neuroethology is driven not by a desire to make machines more human, but to better understand our own minds — and with that, our humanity.

This article The next revolution in neuroscience is happening outside the lab is featured on Big Think.

The post “The next revolution in neuroscience is happening outside the lab” by Jasna Hodžić was published on 12/17/2025 by bigthink.com

Leave a Reply