In 1957, Hollywood released “The Deadly Mantis,” a B-grade monster movie starring a praying mantis of nightmare proportions. Its premise: Melting Arctic ice has released a very hungry, million-year-old megabug, and scientists and the U.S. military will have to stop it.

The rampaging insect menaces America’s Arctic military outposts, part of a critical line of national defense, before heading south and meeting its end in New York City.

Yes, it’s over-the-top fiction, but the movie holds some truth about the U.S. military’s concerns then and now about the Arctic’s stability and its role in national security.

LMPC via Getty Images

In the late 1940s, Arctic temperatures were warming and the Cold War was heating up. The U.S. military had grown increasingly nervous about a Soviet invasion across the Arctic. It built bases and a line of radar stations. The movie used actual military footage of these polar outposts.

But officials wondered: What if sodden snow and vanishing ice stalled American men and machines and weakened these northern defenses?

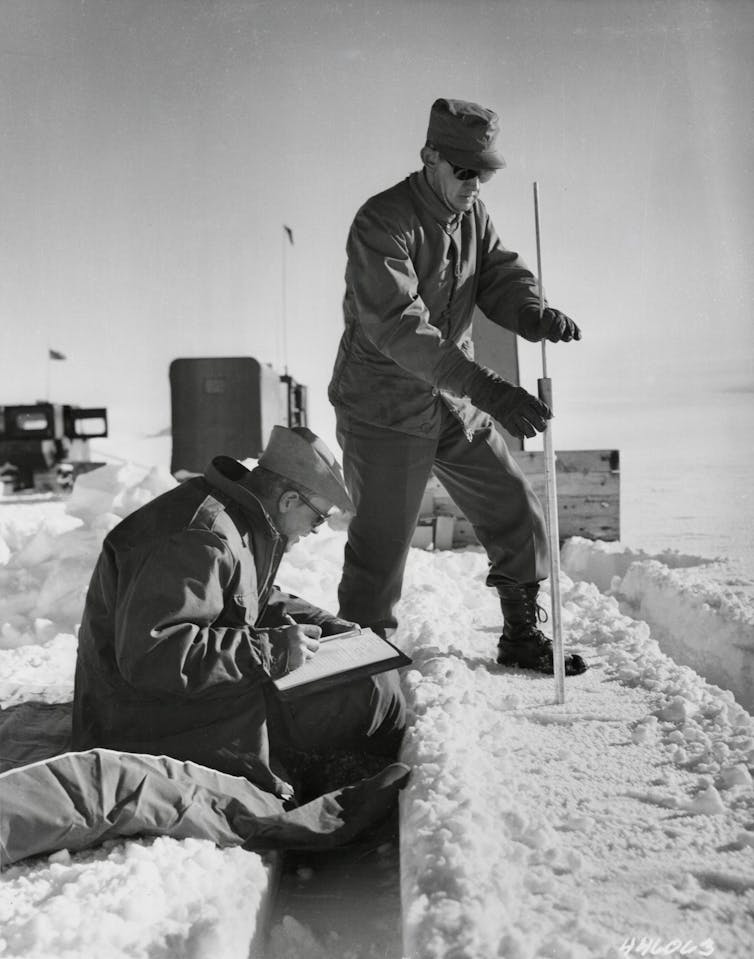

In response to those concerns, the military created the Snow, Ice and Permafrost Research Establishment, a research center dedicated to the science and engineering of all things frozen: glacier runways, the behavior of ice, the physics of snow and the climates of the past.

It was the beginning of the military’s understanding that climate change couldn’t be ignored.

U.S. Army

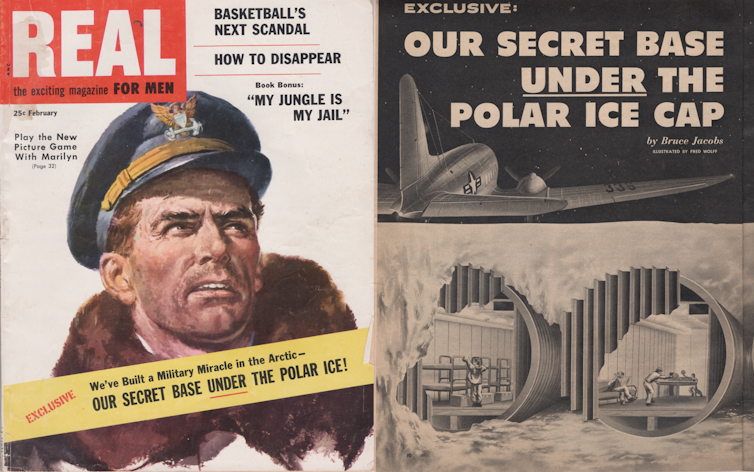

As I was writing “When the Ice is Gone,” my recent book about Greenland, climate science and the U.S. military, I read government documents from the 1950s and 1960s showing how the Pentagon poured support into climate and cold-region research to boost the national defense.

Initially, military planners recognized threats to their own ability to protect the nation. Over time, the U.S. military would come to see climate change as both a threat in itself and a threat multiplier for national security.

Ice roads, ice cores and bases inside the ice sheet

The military’s snow and ice engineering in the 1950s made it possible for convoys of tracked vehicles to routinely cross Greenland’s ice sheet, while planes landed and took off from ice and snow runways.

In 1953, the Army even built a pair of secret surveillance sites inside the ice sheet, both equipped with Air Force radar units looking 24/7 for Soviet missiles and aircraft, but also with weather stations to understand the Arctic climate system.

Paul Bierman collection.

The Army drilled the world’s first deep ice core from a base it built within the Greenland ice sheet, Camp Century. Its goal: to understand how climate had changed in the past so they would know how it might change in the future.

The military wasn’t shy about its climate change research successes. The Army’s chief ice scientist, Dr. Henri Bader, spoke on the Voice of America. He promoted ice coring as a way to investigate climates of the past, provide a new understanding of weather, and understand past climatic patterns to gauge and predict the one we are living in today – all strategically important.

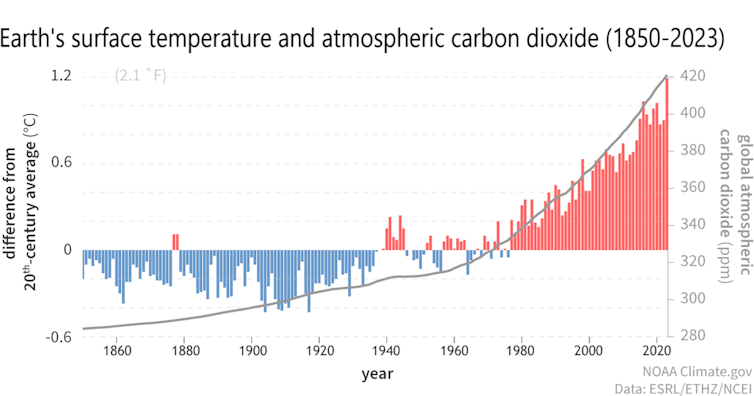

In the 1970s, painstaking laboratory work on the Camp Century ice core extracted minuscule amounts of ancient air trapped in tiny bubbles in the ice. Analyses of that gas revealed that levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere were lower for tens of thousands of years before the industrial revolution. After 1850, carbon dioxide levels crept up slowly at first and then rapidly accelerated. It was direct evidence that people’s actions, including burning coal and oil, were changing the composition of the atmosphere.

Since 1850, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have spiked and global temperatures have warmed by more than 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit (1.3 Celsius). The past 10 years have been the hottest since recordkeeping began, with 2024 now holding the record. Climate change is now affecting the entire Earth – but most especially the Arctic, which is warming several times faster than the rest of the planet.

NOAA

Seeing climate change as a threat multiplier

For decades, military leaders have been discussing climate change as a threat and a threat multiplier that could worsen instability and mass migration in already fragile regions of the world.

Climate change can fuel storms, wildfires and rising seas that threaten important military bases. It puts personnel at risk in rising heat and melts sea ice, creating new national security concerns in the Arctic. Climate change can also contribute to instability and conflict when water and food shortages trigger increasing competition for resources, internal and cross-border tensions, or mass migrations.

The military understands that these threats can’t be ignored. As Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro told a conference in September 2024: “Climate resilience is force resilience.”

Stocktrek Images via Getty Images

Consider Naval Station Norfolk. It’s the largest military port facility in the world and sits just above sea level on Virginia’s Atlantic coast. Sea level there rose more than 1.5 feet in the last century, and it’s on track to rise that much again by 2050 as glaciers around the world melt and warming ocean water expands.

High tides already cause delays in repair work, and major storms and their storm surges have damaged expensive equipment. The Navy has built sea walls and worked to restore coastal dunes and marshlands to protect its Virginia properties, but the risks continue to increase.

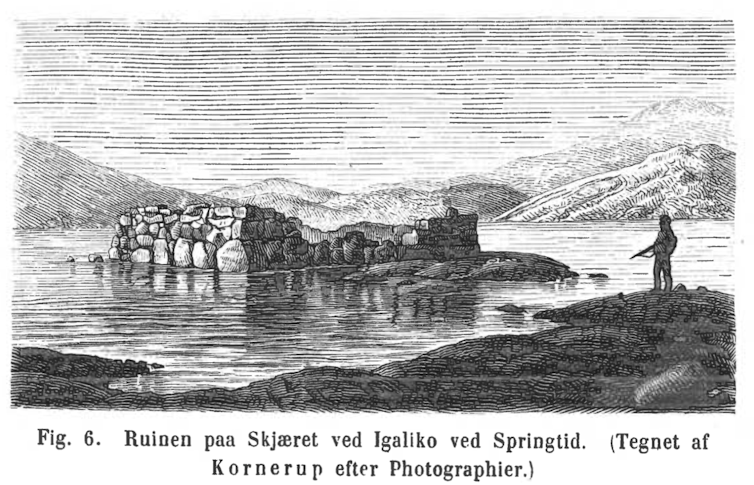

Planning for the future, the Navy incorporates scientists’ projections of sea level rise and increasing hurricane strength to design more resilient facilities. By adapting to climate change, the U.S. Navy will avoid the fate of another famous marine power: the Norse, forced to abandon their flooded Greenland settlements when sea level there rose about 600 years ago.

Steenstrup, K.J.V., and A. Kornerup. 1881. Expeditionen til Julianehaabs distrikt i 1876. MeddelelseromGrønland

Climate change is costly to ignore

As the impacts of climate change grow in both frequency and magnitude, the costs of inaction are increasing. Most economists agree that it’s cheaper to act now than deal with the consequences. Yet, in the past 20 years, the political discourse around addressing the cause and effects of climate change has become increasingly politicized and partisan, stymieing effective action.

In my view, the military’s approach to problem-solving and threat reduction provides a model for civil society to address climate change in two ways: reducing carbon emissions and adapting to inevitable climate change impacts.

The U.S. military emits more planet warming carbon than Sweden and spent more than US$2 billion on energy in 2021. It accounts for more than 70% of energy used by the federal government.

In that context, its embrace of alternative energy, including solar generation, microgrids and wind power, makes economic and environmental sense. The U.S. military is moving away from fossil fuels, not because of any political agenda, but because of the cost-savings, increased reliability and energy independence the alternatives provide.

Frederic J . Brown/AFP via Getty Images

As sea ice melts and Arctic temperatures rise, the polar region has again become a strategic priority. Russia and China are expanding Arctic shipping routes and eyeing critical mineral deposits as they become accessible. The military knows climate change affects national security, which is why it continues to take steps to address the threats a changing climate presents.

The post “The US military has cared about climate change since the dawn of the Cold War – for good reason” by Paul Bierman, Fellow of the Gund Institute for Environment, Professor of Natural Resources and Environmental Science, University of Vermont was published on 03/17/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply