Earth’s average temperature rose more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels in 2024 for the first time – a critical threshold in the climate crisis. At the same time, major armed conflicts continue to rage in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan and elsewhere.

What should be increasingly clear is that war now needs to be understood as unfolding in the shadow of climate breakdown.

The relationship between war and climate change is complex. But here are three reasons why the climate crisis must reshape how we think about war.

Wars and climate change are inextricably linked. Climate change can increase the likelihood of violent conflict by intensifying resource scarcity and displacement, while conflict itself accelerates environmental damage. This article is part of a series, War on climate, which explores the relationship between climate issues and global conflicts.

1. War exacerbates climate change

The inherent destructiveness of war has long degraded the environment. But we have only recently become more keenly aware of its climatic implications.

This follows efforts primarily by researchers and civil society organisations to account for the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from fighting, most notably in Ukraine and Gaza, as well as to record emissions from all military operations and post-war reconstruction.

One study, conducted by Scientists for Global Responsibility and the Conflict and Environment Observatory, has made a best guess that the total carbon footprint of militaries across the globe is greater than that of Russia, which currently has the fourth-largest footprint in the world.

The US is believed to have the highest military emissions. Estimates by UK-based researchers Benjamin Neimark, Oliver Belcher and Patrick Bigger suggest that, if it were a country, the US military would be the 47th-largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world. This would put it between Peru and Portugal.

These studies, though, rest on limited data. Sometimes partial emissions data is reported by military agencies, and researchers have to supplement this with their own calculations using official government figures and those of associated industries.

There is also significant variation from country to country. Some military emissions, most notably those of China and Russia, have proved almost impossible to assess.

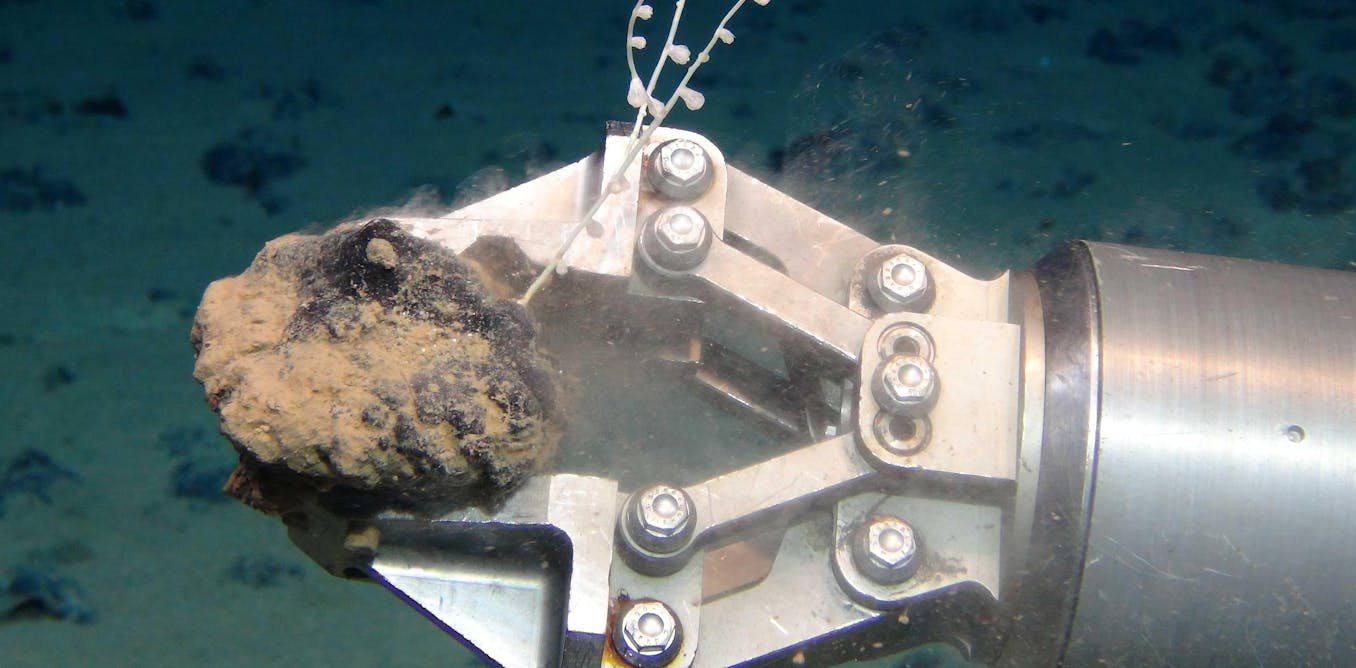

Jeffrey Groeneweg / EPA

Wars can also put international cooperation on climate change and the energy transition at risk. Since the start of the Ukraine war, for instance, scientific cooperation between the west and Russia in the Arctic has broken down. This has prevented crucial climate data from being compiled.

Critics of militarism argue that the acknowledgement of war’s contribution to the climate crisis ought to be the moment of reckoning for those who are too willing to spend vast resources on maintaining and expanding military power. Some even believe that demilitarisation is the only way out of climate catastrophe.

Others are less radical. But the crucial point is that recognition of the climate costs of war increasingly raises moral and practical questions about the need for more strategic restraint and whether the business of war can ever be rendered less environmentally destructive.

2. Climate change demands military responses

Before the impact of war on the climate came into focus, researchers debated whether the climate crisis could act as a “threat multiplier”. This has led some to argue that climate change could intensify the risk of violence in parts of the world already under stress from food and water insecurity, internal tensions, poor governance and territorial disputes.

Some conflicts in the Middle East and Sahel have already been labelled “climate wars”, implying they may not have happened if it were not for the stresses of climate change. Other researchers have shown how such claims are deeply contentious. Any decision to engage in violence or go to war is always still a choice made by people, not the climate.

Harder to contest is the observation that the climate crisis is leading militaries to be deployed with greater frequency to assist with civilian emergencies. This encompasses a wide range of activities from combating wildfires to reinforcing flood defences, assisting with evacuations, conducting search-and-rescue operations, supporting post-disaster recovery and delivering humanitarian aid.

chinahbzyg / Shutterstock

Whether the climate crisis will result in more violence and armed conflict in the future is impossible to predict. If it does, military force may need to be deployed more frequently. At the same time, if militaries are depended upon to help respond to the growing frequency and intensity of climate-related disasters, their resources will be further stretched.

Governments will be confronted with tough choices about what kinds of tasks should be prioritised and whether military budgets should be increased at the expense of other societal needs.

3. Armed forces will need to adapt

With geopolitical tensions rising and the number of conflicts increasing, it seems unlikely that calls for demilitarisation will be met any time soon. This leaves researchers with the uncomfortable prospect of having to rethink how military force can – and ought to be – wielded in a world simultaneously trying to adapt to accelerating climate change and escape its deep dependence on fossil fuels.

The need to prepare military personnel and adapt bases, equipment and other infrastructure to withstand and operate effectively in increasingly extreme and unpredictable climatic conditions is a matter of growing concern. In 2018, two major hurricanes in the US caused more than US$8 billion (£5.95 billion) worth of damage to military infrastructure.

My own research has demonstrated how, in the UK at least, there is growing awareness among some defence officials that militaries need to think carefully about how they will navigate the major changes unfolding in the global energy landscape that are being brought about by the energy transition.

Militaries are being confronted with a stark choice. They can either remain as one of the last heavy users of fossil fuels in an increasingly low-carbon world or be part of an energy transition that will probably have significant implications for how military force is generated, deployed and sustained.

What is becoming clear is that operational effectiveness will increasingly depend on how aware militaries are of the implications of climate change for future operations. It will also hinge on how effectively they have adapted their capabilities to cope with more extreme climatic conditions and how much they have managed to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels.

photos_adil / Shutterstock

In the early 19th century, the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz famously argued that while war’s nature rarely changes, its character is almost constantly evolving with the times.

Recognising the scale and reach of the climate crisis will be essential if we are now to make sense of why and how future wars will be waged, as well as how some might be averted or rendered less destructive.

The post “Three reasons why the climate crisis must reshape how we think about war” by Duncan Depledge, Senior Lecturer in Geopolitics and Security, Loughborough University was published on 09/03/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply