Federal scientists released their annual forecast for Lake Erie’s harmful algal blooms on June 26, 2025, and they expect a mild to moderate season. However, anyone who comes in contact with toxic algae can face health risks. And 2014, when toxins from algae blooms contaminated the water supply in Toledo, Ohio, was a moderate year, too.

We asked Gregory J. Dick, who leads the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research, a federally funded center at the University of Michigan that studies harmful algal blooms among other Great Lakes issues, why they’re such a concern.

NOAA

1. What causes harmful algal blooms?

Harmful algal blooms are dense patches of excessive algae growth that can occur in any type of water body, including ponds, reservoirs, rivers, lakes and oceans. When you see them in freshwater, you’re typically seeing cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae.

These photosynthetic bacteria have inhabited our planet for billions of years. In fact, they were responsible for oxygenating Earth’s atmosphere, which enabled plant and animal life as we know it.

Michigan Sea Grant

Algae are natural components of ecosystems, but they cause trouble when they proliferate to high densities, creating what we call blooms.

Harmful algal blooms form scums at the water surface and produce toxins that can harm ecosystems, water quality and human health. They have been reported in all 50 U.S. states, all five Great Lakes and nearly every country around the world. Blue-green algae blooms are becoming more common in inland waters.

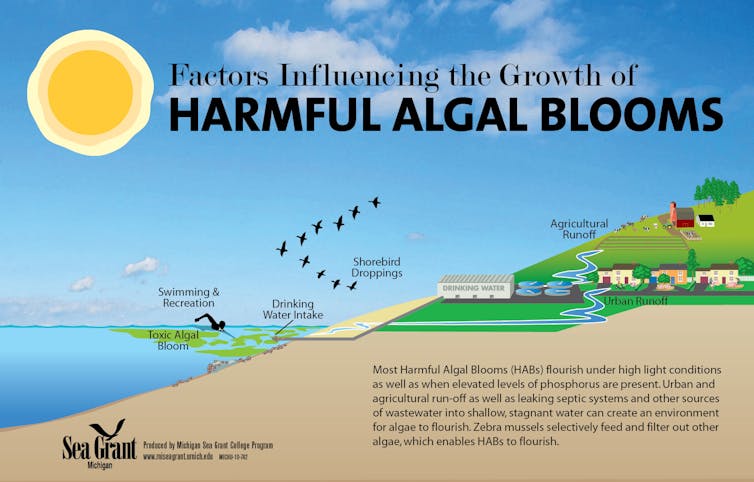

The main sources of harmful algal blooms are excess nutrients in the water, typically phosphorus and nitrogen.

Historically, these excess nutrients mainly came from sewage and phosphorus-based detergents used in laundry machines and dishwashers that ended up in waterways. U.S. environmental laws in the early 1970s addressed this by requiring sewage treatment and banning phosphorus detergents, with spectacular success.

Today, agriculture is the main source of excess nutrients from chemical fertilizer or manure applied to farm fields to grow crops. Rainstorms wash these nutrients into streams and rivers that deliver them to lakes and coastal areas, where they fertilize algal blooms. In the U.S., most of these nutrients come from industrial-scale corn production, which is largely used as animal feed or to produce ethanol for gasoline.

Climate change also exacerbates the problem in two ways. First, cyanobacteria grow faster at higher temperatures. Second, climate-driven increases in precipitation, especially large storms, cause more nutrient runoff that has led to record-setting blooms.

2. What does your team’s DNA testing tell us about Lake Erie’s harmful algal blooms?

Harmful algal blooms contain a mixture of cyanobacterial species that can produce an array of different toxins, many of which are still being discovered.

When my colleagues and I recently sequenced DNA from Lake Erie water, we found new types of microcystins, the notorious toxins that were responsible for contaminating Toledo’s drinking water supply in 2014.

These novel molecules cannot be detected with traditional methods and show some signs of causing toxicity, though further studies are needed to confirm their human health effects.

Ty Wright for The Washington Post via Getty Images

We also found organisms responsible for producing saxitoxin, a potent neurotoxin that is well known for causing paralytic shellfish poisoning on the Pacific Coast of North America and elsewhere.

Saxitoxins have been detected at low concentrations in the Great Lakes for some time, but the recent discovery of hot spots of genes that make the toxin makes them an emerging concern.

Our research suggests warmer water temperatures could boost its production, which raises concerns that saxitoxin will become more prevalent with climate change. However, the controls on toxin production are complex, and more research is needed to test this hypothesis. Federal monitoring programs are essential for tracking and understanding emerging threats.

3. Should people worry about these blooms?

Harmful algal blooms are unsightly and smelly, making them a concern for recreation, property values and businesses. They can disrupt food webs and harm aquatic life, though a recent study suggested that their effects on the Lake Erie food web so far are not substantial.

But the biggest impact is from the toxins these algae produce that are harmful to humans and lethal to pets.

The toxins can cause acute health problems such as gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, fever and skin irritation. Dogs can die from ingesting lake water with harmful algal blooms. Emerging science suggests that long-term exposure to harmful algal blooms, for example over months or years, can cause or exacerbate chronic respiratory, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal problems and may be linked to liver cancers, kidney disease and neurological issues.

AP Photo/Haraz N. Ghanbari

In addition to exposure through direct ingestion or skin contact, recent research also indicates that inhaling toxins that get into the air may harm health, raising concerns for coastal residents and boaters, but more research is needed to understand the risks.

The Toledo drinking water crisis of 2014 illustrated the vast potential for algal blooms to cause harm in the Great Lakes. Toxins infiltrated the drinking water system and were detected in processed municipal water, resulting in a three-day “do not drink” advisory. The episode affected residents, hospitals and businesses, and it ultimately cost the city an estimated US$65 million.

4. Blooms seem to be starting earlier in the year and lasting longer – why is that happening?

Warmer waters are extending the duration of the blooms.

In 2025, NOAA detected these toxins in Lake Erie on April 28, earlier than ever before. The 2022 bloom in Lake Erie persisted into November, which is rare if not unprecedented.

Scientific studies of western Lake Erie show that the potential cyanobacterial growth rate has increased by up to 30% and the length of the bloom season has expanded by up to a month from 1995 to 2022, especially in warmer, shallow waters. These results are consistent with our understanding of cyanobacterial physiology: Blooms like it hot – cyanobacteria grow faster at higher temperatures.

5. What can be done to reduce the likelihood of algal blooms in the future?

The best and perhaps only hope of reducing the size and occurrence of harmful algal blooms is to reduce the amount of nutrients reaching the Great Lakes.

In Lake Erie, where nutrients come primarily from agriculture, that means improving agricultural practices and restoring wetlands to reduce the amount of nutrients flowing off of farm fields and into the lake. Early indications suggest that Ohio’s H2Ohio program, which works with farmers to reduce runoff, is making some gains in this regard, but future funding for H2Ohio is uncertain.

In places like Lake Superior, where harmful algal blooms appear to be driven by climate change, the solution likely requires halting and reversing the rapid human-driven increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

The post “Toxic algae blooms are lasting longer than before in Lake Erie − why that’s a worry for people and pets” by Gregory J. Dick, Professor of Biology, University of Michigan was published on 06/26/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply