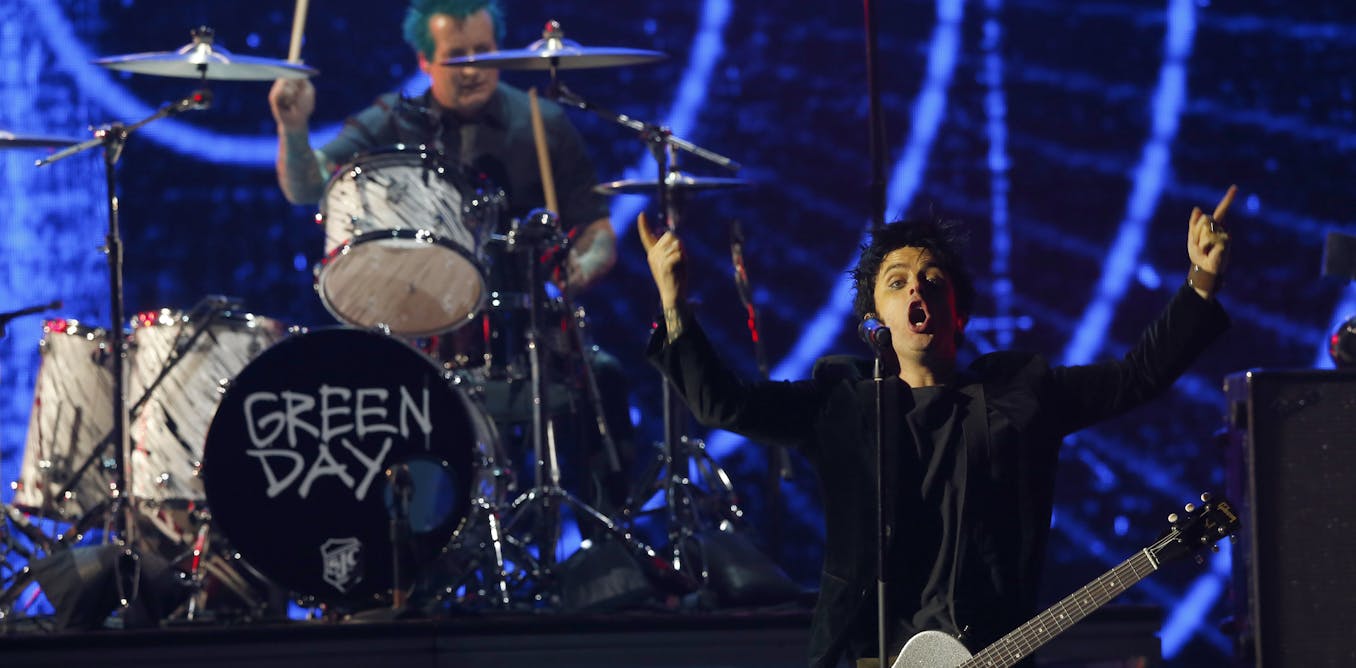

When tickets for Green Day’s 2025 Australian tour went on sale, fans joined a queue – a ritual that has been practised for decades on footpaths, on phones, and now online.

But as Green Day fans reached the purchase point, the price varied. For some, a seated ticket rose as high as A$500.

A week earlier, tickets to the Oasis reunion tour in the United Kingdom – arguably the hottest ticket in the world – rose by hundreds of pounds while on sale.

Ticketmaster calls this “In Demand” pricing. It’s an instance of what is more broadly known as dynamic pricing.

What is dynamic pricing?

Dynamic pricing is well established in tourism and air travel. In these markets, supply is fixed – the number of hotel rooms and plane seats – but demand has peaks and troughs. Prices are adjusted to maximise profit and to shape consumer behaviour.

However, there are significant differences when it comes to music concert tickets.

Consumers see accommodation and transport prices up front, before committing to a “queue”. When it comes to the current practice for live music dynamic pricing, costs aren’t seen until they reach the front of the queue. There, consumers are presented with two numbers: a price and a timer counting down.

And unlike accommodation and transport services, each concert by a major touring artist (let alone Oasis) is a much more limited commodity.

How much is a ticket?

In 1964, Australians paid up to $3.70 ($63 in today’s terms) to see the world’s hottest act, The Beatles.

The relative price of concert tickets has changed with the economic and cultural role of live music.

AAP Image/James Ross

For decades, concerts were primarily a way to promote record sales, with physical albums being the main source of revenue. Since the digital de-valuing of recorded music, live performance has become increasingly essential for the industry.

So ticket prices have risen, and with them the drive for everyone involved to get their cut.

Even better than a cut is control.

The live music market

Will dynamic pricing be accepted or rejected by the market? This question assumes a competitive marketplace. In today’s live music sector, competition is on the wane.

Australia’s live music market is dominated by three key players, two of which are owned by foreign multinationals, with Live Nation Entertainment (which owns Ticketmaster, Moshtix, and majority-shares in many Australian festivals and venues) dominating much of the market for international touring acts.

Despite the crisis in local and grassroots live music, Live Nation Entertainment has reported record revenues for the last two years.

Live Nation’s subsidiary Ticketmaster says dynamic pricing enables “artists and other people involved in staging live events to price tickets closer to their true market value”.

The promoter of Green Day’s tour is Live Nation, which manages artists, owns Ticketmaster and also controls some of the venues, and has similar interests in the Oasis tour – extending even to security. In the case of Green Day, Live Nation controls most of the supply chain.

In such a concentrated market, the test for a new pricing model is less about what consumers will choose, than what they can tolerate. Is this “true market value”, or an abuse of market power?

Could the government intervene?

Ticketmaster’s dynamic pricing is under investigation by fair trading authorities in Europe and the UK. The United States government is suing Live Nation-Ticketmaster for misuse of monopoly power.

Australian authorities are yet to announce any equivalent actions.

EPA/JIM LO SCALZO

Justifications for market intervention are to sustain an industry – because of its economic or social value – and to extend equitable access to important goods and services. Utilities, insurance, health, and education fall into this category.

But what about culture?

Shared group experiences are becoming increasingly rare in our atomised, algorithm-driven world. Concerts contribute to social cohesion and build communities that otherwise would have less opportunities to meet.

If such experiences become prohibitively expensive, many will be excluded from one of the sweetest fruits of the social contract. Rather than “market value”, this would essentially amount to a failure of policy.

Stadium concerts have been on the rise in Australia for years even as other events have struggled, with the live music sector becoming more top-heavy as it consolidates around major events; a relatively recent phenomenon.

The use of dynamic pricing for Green Day tickets imports a new twist into the Australian music market, and fans are understandably upset.

The decision reflects a band that has moved a long way from their DIY origins playing all-ages communes and squats in the East Bay area, and a music industry that looks nothing like the early 1990s, when a band like Green Day could work their way up the “toilet circuit” to become a major label smash hit.

Will dynamic pricing stick – or will it force attention to the structural issues in our live music sector? With today’s news that Dua Lipa tickets will also be subject to the practice, it seems that we may be stuck with it. For now.

The post “What is ‘dynamic pricing’ for concert tickets? It can cost you hundreds of dollars while you queue” by Ben Green, Research Fellow, Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University was published on 09/20/2024 by theconversation.com

![Animals vs. Water: Hilarious Moments! 😂 [2025 Edition] – Video Animals vs. Water: Hilarious Moments! 😂 [2025 Edition] – Video](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/F1_AvAuQI5M/maxresdefault.jpg)

Leave a Reply