The wildflowers of Britain include all manner of treasures – yet many people are only aware of a few, such as bluebells and foxgloves. A lot of its other flora are rare because of Britain’s location at the northern, western or even southern edges of their natural geographic – and hence climatic – ranges.

In fact, Britain has over 1,000 native species of wildflower, including 50 kinds of orchid, a few species like sundew that use sticky tentacles to eat insects, and others such as toothwort that live as parasites, plugging their roots into other plants to suck on their sap like botanical mosquitoes. There are even a few species, such as the ghost and bird’s-nest orchids, that extort all their food from soil fungi.

Many people think of plants as nice-looking greens. Essential for clean air, yes, but simple organisms. A step change in research is shaking up the way scientists think about plants: they are far more complex and more like us than you might imagine. This blossoming field of science is too delightful to do it justice in one or two stories.

This story is part of a series, Plant Curious, exploring scientific studies that challenge the way you view plantlife.

I’ve been an obsessive plant hunter since I was seven years old. Wishing to share this wonder with others, I began running informal classes in plant identification about 17 years ago. This has grown into a quest to get people looking at and identifying wildflowers, in the hope of curing “plant blindness” – the inability to see or notice plants in your own backdrop – which afflicts so many people.

Initially, I taught plant ID classes in person. But when the pandemic hit, I needed an online resource with high-quality images of British plants arranged by family. No such resource existed online, so I decided to create it.

And so began a five-year mission to photograph the entire British flora myself. That process is now close to complete, and the results can be seen on the website I have created.

This photographic quest took me to all parts of the British Isles – to famous rare-plant hotspots like the Lizard in Cornwall, Teesdale in county Durham and Ben Lawers in the Scottish highlands, and from the north coast of Scotland (where the endemic Scottish primrose grows) to the chalk downs of Kent, where many rare orchids can be found.

I did cheat a bit – for example, using living collections of rare plants in Edinburgh’s Royal Botanic Garden and the incredible Rare British Plants Nursery in Wales.

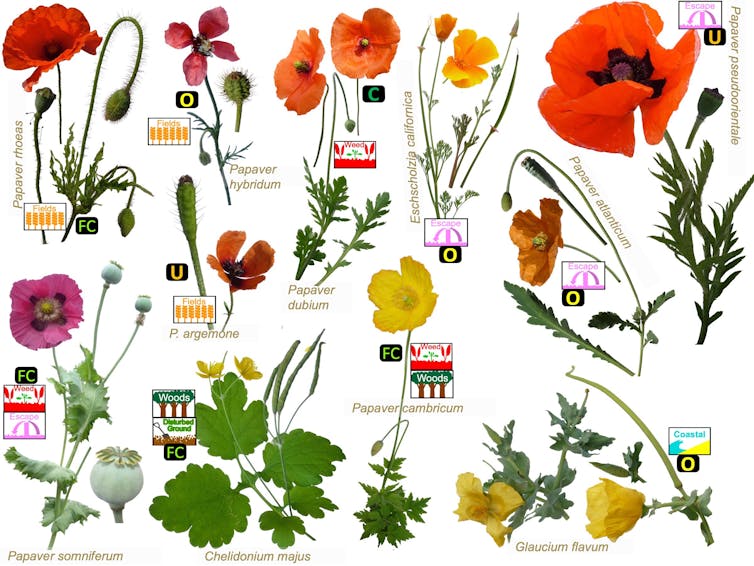

Richard Milne, Author provided (no reuse)

Brownfield havens

Oddly, cities and especially brownfield sites can be havens for biodiversity. Recently, a student and I both collected material from York for a plant ID session. I pottered around pavements and riverside concrete while she cycled to the nearest woodland – but I got more species.

Brownfield sites are often alkaline (from the lime in concrete) and nutrient-poor, both of which encourage plant diversity. This is also why chalk and limestone grassland is so rich in species.

Species that struggle for a foothold among a countryside dominated by agriculture can thrive in such apparently unpromising places. For example, Monktonhall bing, a coal slag heap five miles from the centre of Edinburgh, is home to numerous locally rare species.

The nearby wasteground was equally diverse but is being lost to development – although the rare yellow bird’s-nest plant which fellow scientist Vlad Krivtsov and I discovered there has narrowly escaped destruction, so far.

In some ways, brownfield sites are the silver lining to all the habitat destruction humans have caused. But not all these sites are equal, of course, and it would be wonderful if developers would choose the less biodiverse brownfield sites to build much-needed housing.

Our rare flora

Some species have turned out to be a lot rarer than expected. I made extensive use of maps and data from the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, and this showed that species like the downy currant had far fewer sites than I had assumed. This reflects a general trend of decline in our native flora.

The slender naiad appears to have been wiped out in England by sewage discharges, while the endemic English sandwort may be heading towards extinction due to climate change.

Other species, such as the lesser butterfly orchid, have been steadily declining over many decades – probably due to so much of the British countryside being rendered a biological desert by monoculture farming, spruce plantations or intensive grazing. Research shows less-intensive grazing might benefit Britain’s biodiversity.

I was also able to take fine images of rare British species during trips to Norway, Estonia and Corfu. Military and lady’s slipper orchids are all far more common in Estonia than Britain, and in Corfu I found a single roadside ditch with perhaps more adderstongue spearwort plants than the entire UK population.

Most species look similar at home or abroad. But the marsh gentian looked so unexpectedly different in Estonia that I had to track it down again in the UK.

Try it yourself

In late summer, the number of species in flower declines a little, but many large and spectacular flowers remain to be found. Canadian goldenrod, Michaelmas daisy and Indian balsam are all garden escapes, displacing native flora but providing a bounty of food for pollinators.

If you can visit alkaline grassland such as chalk downs, many native treasures await discovery, such as purple autumn gentians and the spiralling flowers of the autumn lady’s tresses orchid. However, almost any site will turn up one or two interesting plants, which my website can help you identify.

Richard Milne, Author provided (no reuse)

It’s true that these days, you can point a mobile phone app at a plant and get a name for it, so why try to teach people identification skills? Well, we don’t learn much when an app or a teacher simply gives us the answer. We learn from getting there ourselves.

My website uses plant families – natural groupings of related species. Just answer a few simple questions about your mystery flower’s number of petals, symmetry and arrangement, and you’ll get a list of families it might belong to. It then generates a picture ID guide, built from my images and comprising only those families, through which you can seek out your plant – all the while, learning to recognise each family of plants for yourself.

In my own quest, a handful of species still elude me – many of them hard-to-identify grasses or ephemeral rarities that seldom appear in the same place two years running. But these are unlikely to concern most amateur plant hunters as there are so many wildflowers to enjoy out there. Try improving your own ID skills at namethatplant.org.

The post “What I’ve learned from photographing (almost) every British wildflower” by Richard Milne, Senior Lecturer in Plant Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh was published on 09/04/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply