Climate modelling is spoken about often by climate scientists. These complex, computer-generated calculations enable scientists to make predictions about the climate of the future.

Information generated from climate models is often shared through graphs, maps, images, animations or reports. These visual formats are excellent for accurately communicating data, statistics and recommendations, but can feel inaccessible for non-expert members of the general public.

David Attenborough said “saving our planet is now a communications challenge”. This points to the gap between the knowledge about the actions needed to address climate change, and motivation towards taking this action.

In this gap, musical creativity and imagination can offer new pathways towards awareness and understanding. This can contribute to how we collectively develop climate communication.

I have been collaborating with a team of artists and scientists on Dark Oceanography to explore new ways of sharing climate information.

Beyond words

The intangible nature of music provides exceptional opportunities to convey things that words, numbers or images cannot.

Music is a form of knowledge that is experienced, as it is felt through the body by the listener. Music provides a different means of engagement to inform our understanding of environmental phenomena – and therefore how we understand climate issues.

Climate models move beyond how things are or have been. They predict how things might be, and offer a window to view the future. Dark Oceanography takes modelling into new territory.

As director and a performer of Dark Oceanography, I worked with composer Kate Milligan, music technologist Aaron Wyatt, oceanographer Navid Constantinou and a team of percussionists.

Darren Gill

Stepping beyond prediction into imagination, Dark Oceanography questions the nature of data and how it can be communicated. By integrating data of ocean eddies with experimental music and spatial audio technology, this work creates a fictional climate model to be experienced through new music.

Translating eddies

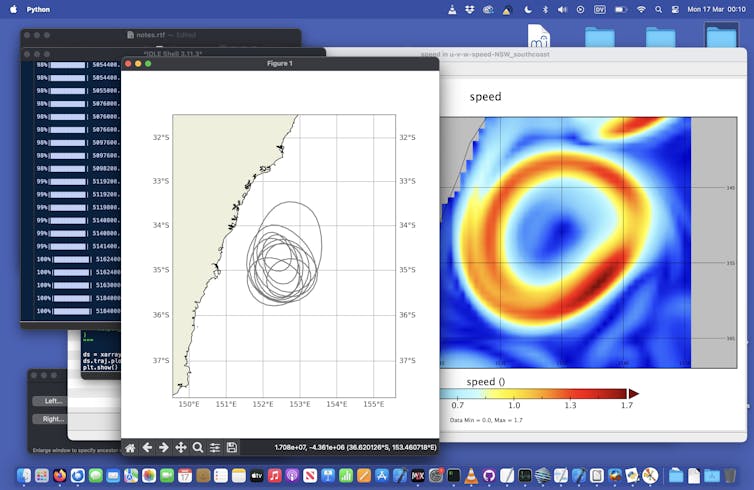

Ocean eddies are circular water movements like big whirlpools, found throughout the ocean. Although they can be up to 200 kilometres in diameter and descend deep beneath the ocean surface, they are unseen from land.

Eddies propel heat, energy and nutrients through the ocean. They play a key role in the circulation of water and heat in the ocean. Research shows the behaviour of eddies is changing and becoming more active. However, eddies are not always included in climate projections.

Dark Oceanography invites the audience to experience the vitality of these ocean systems, translating and transforming eddy datasets into music.

Darren Gill

The live performances of three percussionists are captured by close microphones and sent swirling around the performance space through a multi-channel spatial audio system. Seated in the round and ringed by stations of percussion instruments, the audience is submerged in the circular motion of 360-degree sound.

The audience experience is like listening to an eddy from the inside.

The integration of scientific data with creative practice offers more than just innovative communication methods for science. It also offers new possibilities for musical composition and performance.

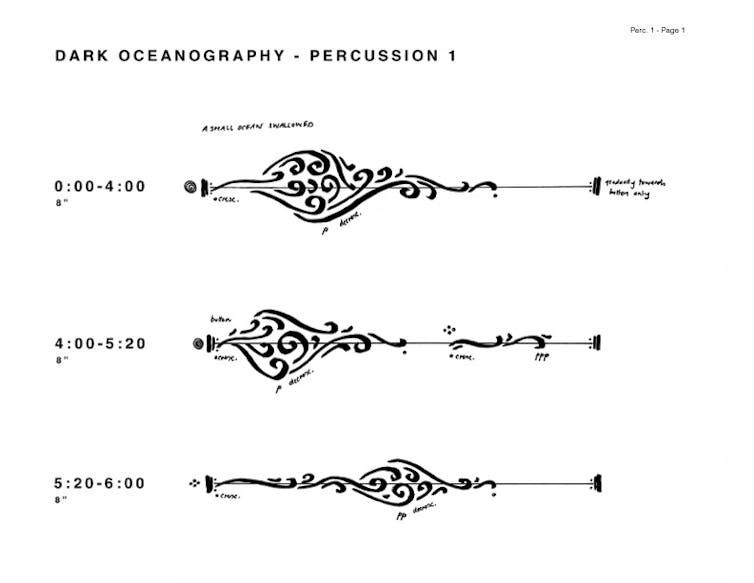

In Dark Oceanography, the circular motion of ocean eddies permeates every aspect of the work. This includes the instrument selection, the performers’ gestures and techniques, the notation and audience seating.

Kate Milligan

The continuous circular motion of eddies offers a metaphor for restarting, for renewal. Each iteration brings a level of change and evolution. The piece descends through the dataset in three stages from the ocean’s surface to nearly one kilometre underwater. The percussionists begin by sounding delicate glass and metal instruments, before the soundworld deepens with low drums and the sinking, sliding sounds of timpani.

A changing feat

The dataset that propels the music was extrapolated from existing ocean simulations, following the pathways of eddies from the Eastern Australian Current. As performance locations for this work change, so will the data, integrating new eddies drawn from local ocean currents. The musical experience also changes with different eddies.

Data provided by Navid Constantinou. Image credit: Aaron Wyatt.

The impact of changing ocean eddy systems on the global climate is currently unknown. This confluence of sound and science leans into the unknown, and offers a way of navigating uncertainty through music. Dark Oceanography shows us that there are many ways to imagine the future.

This article is part of Making Art Work, our series on what inspires artists and the process of their work.

The post “What would a climate model made from music sound like? This team of artists and scientists has created one” by Louise Devenish, Senior Lecturer and director of The Sound Collectors Lab, Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music and Performance, Monash University was published on 08/05/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply