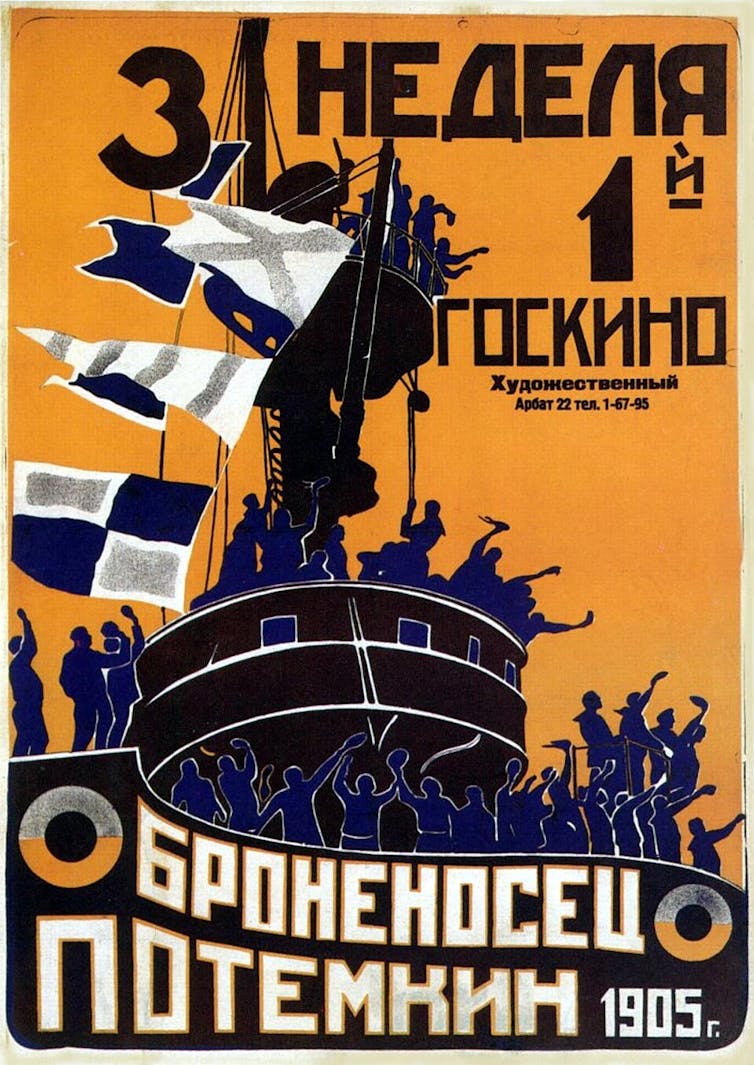

A landmark film in Russian cinema, Sergei Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin may have first been shown in Moscow on December 24 1925, but its enduring appeal and relevance are evident in the many homages paid by film-makers in the century that followed. So what made this film, known for its cavalier treatment of historical events, one of the most influential historical films ever made?

Britannica / Wikipedia

The story of the making of the film provides some answers. Following the success of his 1924 debut Strike, Eisenstein was commissioned in March 1925 to make a film that would mark the 20th anniversary of Russia’s revolution in 1905. This widespread popular uprising was triggered by poor working conditions and social discontent swept through the Russian Empire, posing a challenge to imperial autocracy. The attempt failed but the memory lived on.

Originally titled The Year 1905, Eisenstein’s film was envisaged as part of a nationwide cycle of commemorative public events across the Soviet Union. The aim was to integrate the progressive parts of Russian history before the 1917 Revolution – in which the general strike of 1905 assumed central place – into the fabric of the new Soviet life afterwards.

The original screenplay envisioned the film as the dramatisation of ten notable, but unrelated, historical episodes from 1905: the Bloody Sunday massacre, the antisemitic pogroms and the mutiny on the imperial battleship Prince Potemkin, among others.

Filming the mutiny, recreating the history

The principal photography started in summer 1925, but yielded little success, after which the increasingly frustrated Eisenstein moved the crew to the southern port of Odessa. He decided to drop the loose episodic structure of the script and refocus the film on just one episode.

The new screenplay was solely based on the events of June 1905, when the sailors on the battleship Prince Potemkin, at the time docked near Odessa, rebelled against their officers after they were ordered to eat rotten meat infested with maggots.

The mutiny and the follow-up events in Odessa were now to be dramatised in five acts. The opening two acts and the closing fifth corresponded to the historical events: the sailors’ rebellion and their successful escape through the squadron of loyalist ships, respectively.

The two central parts of the film, which describe the solidarity of the people of Odessa with the mutineers, were written anew and were only loosely based on historical events. Curiously, over the century of the film’s reception, its reputation as a quintessential historical narrative rests mainly on these two acts. What accounts for that paradox?

Wikipedia

The answer may lie in the central two episodes, particularly the fourth, with its poignant depiction of a massacre against unarmed civilians – including the famous scene of a baby in a runaway pram, bouncing down the steps – that imbue the film with powerful emotional resonance and grant it a sense of moral high ground.

Also, while almost entirely fictional, the famous Odessa Steps sequence integrates many of the historically grounded themes from the original screenplay, namely those of widespread antisemitism and oppression of the Tsarist authorities against its people.

These events are then emphatically visualised through Eisenstein’s idiosyncratic use of montage, in which reiterative patterns of the suffering of the innocent foreground the theme of the faceless brutality of the Tsarist oppressor. The film’s universal moral message is thus rendered in a form that is at once visceral and widely readable.

The Battleship Potemkin can be seen as an act of collective memory that sparks and manages an emotional reaction in the viewer, through which the past and the present are negotiated in a particular way. But, a century on, Eisenstein’s negotiation of the past, so insistent on establishing an emotional rapport with the viewer and recreating history, is inseparable from our own acts of remembrance and history-making.

From the vantage point of 2025, Eisenstein’s Potemkin, with its revolutionary idealism and the promise of a better society, has lost much of its appeal in the wake of the betrayal of the same ideals, from the Stalinist purges of the 1930s to the ongoing devastation of Ukraine. What contemporary viewers need is the revitalisation of the film’s original message in new, ever-changing contexts, urging resistance to power and oppression, and expressing solidarity with the marginalised and oppressed.

Echoes in modern film

It is fitting that this year saw the BFI (the British Film Institute) release a restored version of Battleship Potemkin, for the film has had such a profound and pervasive impact on western visual culture that many viewers may not realise how deeply its language is rooted in mainstream cinema.

Alfred Hitchcock famously adopted Eisenstein’s rapid, chaotic editing techniques in the shower scene in Psycho (1960), where the horror emerges less from what is shown than from what is suggested through montage. He also makes an explicit nod to Eisenstein in the film’s second major killing, in which the murder takes place on the staircase of the Bates house.

This was a scenario later echoed in many films, including Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) by Jack Nicholson’s Joker. Nicholson himself had earlier enacted a violent confrontation on a staircase in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), while Todd Phillips’s Joker (2019) would become emblematic for a controversial dance sequence on a flight of public steps.

William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), likewise, appears to owe a stylistic debt to Eisenstein, with two pivotal deaths occurring at the base of a now-iconic Georgetown stairway. Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985) gestures toward Eisenstein in parody, but it is Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables (1987) that remains the most explicit homage to the Odessa step sequence, with its baby in a runaway pram scene, which places Eisenstein’s influence centrally at the heart of modern Hollywood cinema.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The post “why Sergei Eisenstein’s powerful silent film remains unforgettable” by Dušan Radunović, Associate Professor/Director of Studies (Russian), Durham University was published on 12/23/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply