After a new relationship with pets was forged during COVID lockdown and the phenomenon of Bluey, we now have the definitive cats and dogs show presented by the National Gallery of Victoria.

Can there be an intelligent show about canines and felines that goes beyond a collection of feelgood images of our favourite pets? This exhibition sets out to achieve this and, at least in part, succeeds.

A central question concerning pets and people is how we position ourselves in relationship to animals. If we adopt a Judeo-Christian position – that of Adam naming and having power over all of the animals on earth – then there is the power relationship of ownership.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased NGV Foundation, 2019 © Venkat Shyam, courtesy of Minhazz Majumdar

Alternatively, as understood by many First Nations peoples, many Asian civilisations and popularised by such writers as Joseph Campbell, there are common animal powers that mystically unite humankind with nature.

The dogs and cats that share our lives are also our distant (perhaps not that distant) ancestors. They understand us so intimately because they are part of us and we are part of them.

Most pet owners already know this. We did not need Rupert Sheldrake to tell us that dogs know when their owners are coming home, but, by him telling us, this confirms in our minds we are not simply crazy.

Nomenclature also matters – “owners”. As pointed out in the excellent book that accompanies this exhibition, dogs may have masters, while cats have only servants.

Do we really own our dogs and cats or simply provide for their physical needs while they support us in countless ways?

Companions over time

When it comes to dogs and cats represented in art, the weirdness exposed in this exhibition lies in the social and ideological values held in various human societies.

The Christian tradition saw cats as sinister – Satan’s little helpers and the essential attribute of witches – while dogs are noble and above all else designate fidelity. The dog is a symbol of faith, protection and companionship. The Bible is silent on cats, with a single possible passing reference in the Old Testament, while dogs are mentioned over 40 times.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1956

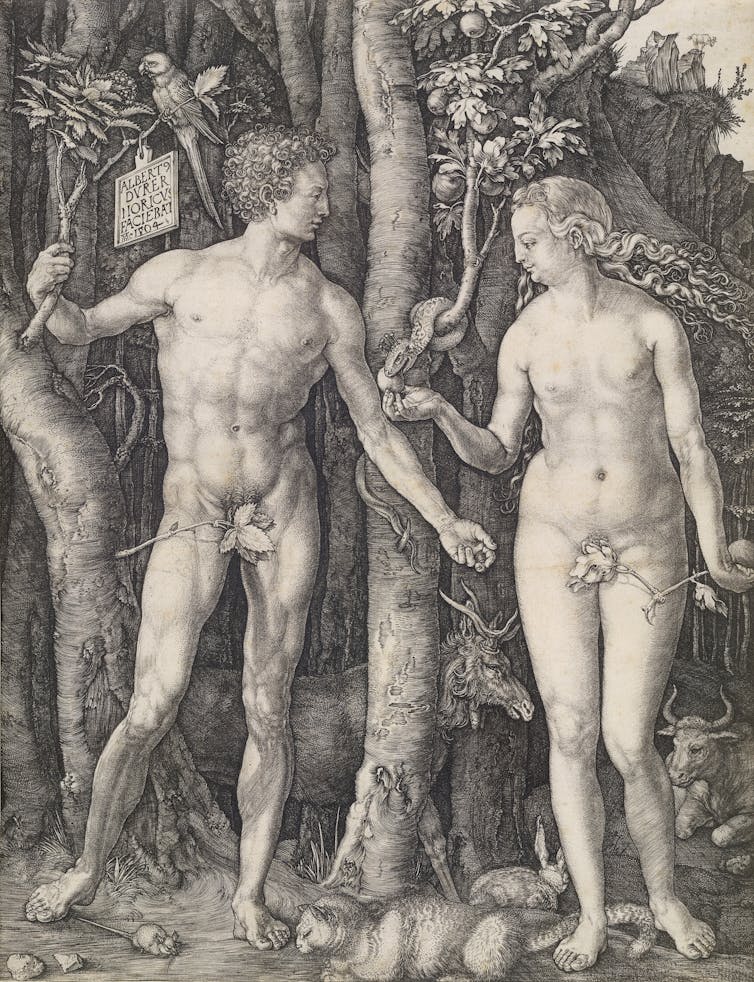

Albrecht Dürer’s magnificent engraving Adam and Eve (1504) sums up much of the traditional Christian attitude to cats. The cat at Eve’s foot represents the choleric humour – cruelty and pride – and its tail entwines Eve’s feet echoing that of the serpent who gives her the forbidden fruit that leads to their expulsion from Paradise and the advent of death.

In the etchings of Rembrandt and the aquatints of Goya, the demonic cat joins witches and other powers of darkness.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1976

A mysterious kind of folk

The cat in many cultures is also associated with seduction, debauchery and eroticism. The NGV exhibition is particularly rich in examples of this category.

This includes Jan Steen’s tavern interior (1661–65), Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s May Belfort (1895) and the great painting by Balthus, Nude with cat (1949).

National Gallery of Victoria Felton Bequest 1952 (2949 – 4)

While the cat may be omnipresent, its actual participation in the events surrounding it frequently remain ambiguous.

As the great observer of human behaviour, Sir Walter Scott, once commented: “Cats are a mysterious kind of folk”.

Man’s best friend

Dogs, in keeping with their reputation as man’s best friend, are superficially more knowable to people because dogs already know what to expect.

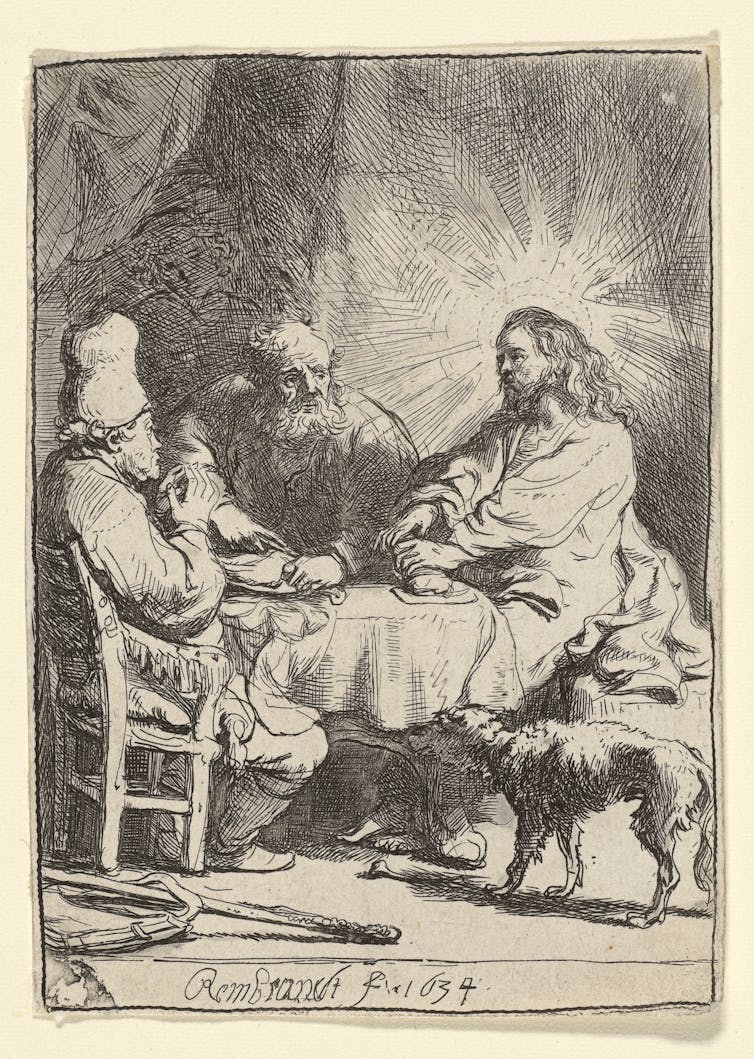

Rembrandt, in Christ at Emmaus: the smaller plate (1634) has the faithful dog standing at Christ’s feet ready to protect the Saviour.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1958

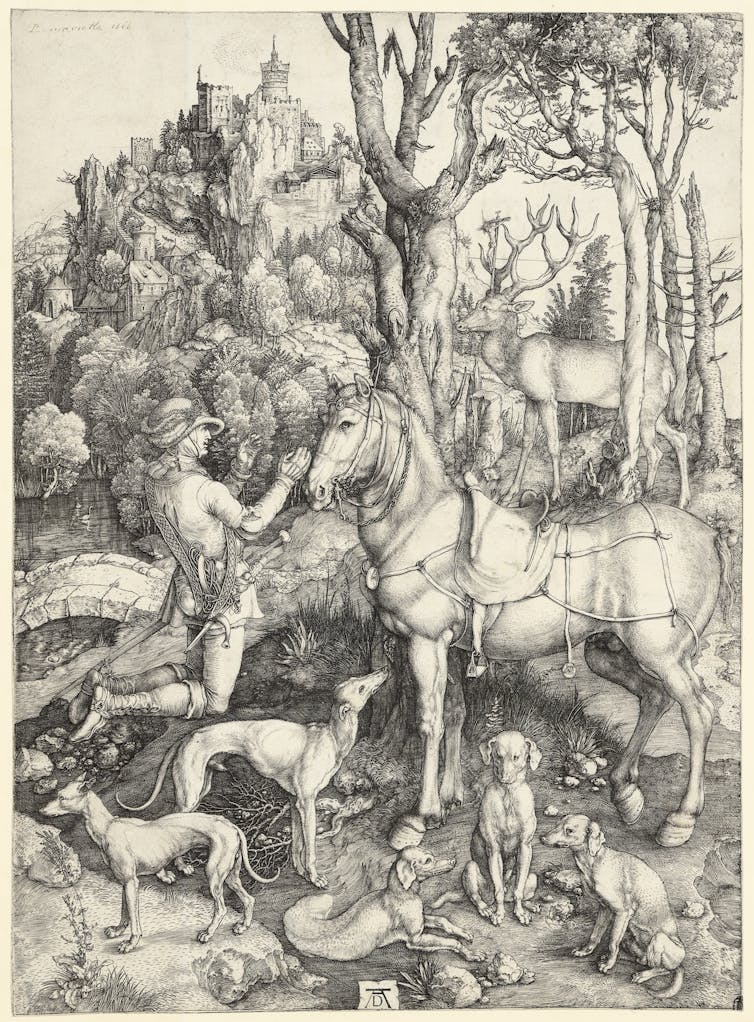

In Dürer’s Saint Eustace (ca.1501), the dogs are not only noble witnesses to the conversion of the Roman general to Christianity, but the five dogs are shown from different angles and positions to celebrate the beauty of the canine.

This is one of the great dog studies of Western civilisation.

Etching: five dogs, a horse and a man.

The exhibition features Aboriginal dog dreaming barks and wooden sculptures of dingos. In the coastal community of Aurukun in Far North Queensland, the dingo, or ku’, are ancestral beings that carry a special significance for the artists and their community.

The dogs are unique with their specific characters but also tap into an ancestral history.

Photo: Tom Ross

Throughout human history, dogs were also status symbols and an expression of their owner’s personality from William Hogarth’s pug, called Trump, to David Hockney’s dachshunds, Stanley and Boodgie.

Many a maiden in 19th and 20th century Europe would establish their reputation through their highly groomed and ridiculously attired poodle or lapdog as richly testified to in this exhibition.

Dogs also carried their owner’s personality. Pierre Bonnard’s dogs and Grace Cossington Smith’s cats tell us as much about their owners as they do about the personality of the animal.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Presented by the National Gallery Society of Victoria, 1967 © Estate of Grace Cossington Smith

Humour and reverence

About 250 furry creatures from the collection of the NGV have been brought together for this exhibition by curators Laurie Benson and Imogen Mallia-Valjan. You meet farm dogs and Felix the Cat with cats and dogs kept separate on different sides of the rooms.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1922

Although this exhibition is raining cats and dogs, they are presented with respect, sometimes with humour and occasionally with reverence.

In the past we thought about how we shaped the world of our canine and feline companions – now we increasingly are starting to understand how they have shaped and enriched our world.

This wonderful exhibition explores part of this journey of realisation.

Disclaimer: Sasha Grishin all of his life has shared his home with dingos and dogs.

Cats & Dogs is at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia until July 20 2025.

The post “the NGV gives us the definitive exhibition” by Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, Australian National University was published on 10/31/2024 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply