What is a peaceful society? When peacebuilders or policymakers think about peace, they have to decide what they mean by it – what kind of society they are trying to build.

The answers to these questions will determine what is done to build peace.

In the process of finding the answers, communication between citizens is essential. But it has to be the right kind of communication. It shouldn’t amplify divisions or cause further conflict. Instead it should encourage the rebuilding of cooperative societies.

These ideas come together in a model I have developed and refer to as “communicative peacebuilding”.

I’m a scholar of communication in peacebuilding and have tried to help find ways to bring peace in African societies.

In my view, communicative peacebuilding offers endless possibilities for building peace that lasts.

The model is flexible about the vehicle used for communication. It can be adapted to whoever is involved (men, women, children, former combatants, peacebuilders or government agents). It can be used for unmediated talks and debates, factual mass media (news and documentaries) and fictional mass media (literature, poetry and soap operas). It can work with the visual arts (photography, painting, memes and architecture) and performing arts (theatre, music and dance). Even sport can be used as a communicative exercise to overcome differences.

It’s based on three building blocks and the right kind of communication.

Building blocks for peace

In my model, the three building blocks of peace are:

The first building block is a commitment to face the future, stop blaming people for what happened in the past, and be willing to compromise.

The second means acknowledging that everyone is equally a citizen. It’s being willing to work towards a common good, and respecting everyone’s right to disagree without fear of violence.

The third is about capacity and civil competencies. It involves individual knowledge and building institutions (like election agencies, press and legal institutions) that work on behalf of all members of society in fair ways.

Societies where these three building blocks are in place are able to manage conflict, divisions and disagreement in non-violent ways.

However, especially after a civil war or violent conflict, getting to this kind of cooperation is difficult. Even when there is goodwill and when many people want peace.

Citizens have to learn to see former enemies as equally human – people they can work with and share a society with. And all need to learn the communication skills for non-violent negotiation.

The skill of civility

The skill I believe is most essential in all this is what I call discursive civility. It relies on each person making three commitments:

-

manage your negative emotions and express them constructively

-

listen to and hear others – they may be right; you might learn from them

-

contribute only in ways that support peace; explain your views clearly and show how they contribute to cooperation.

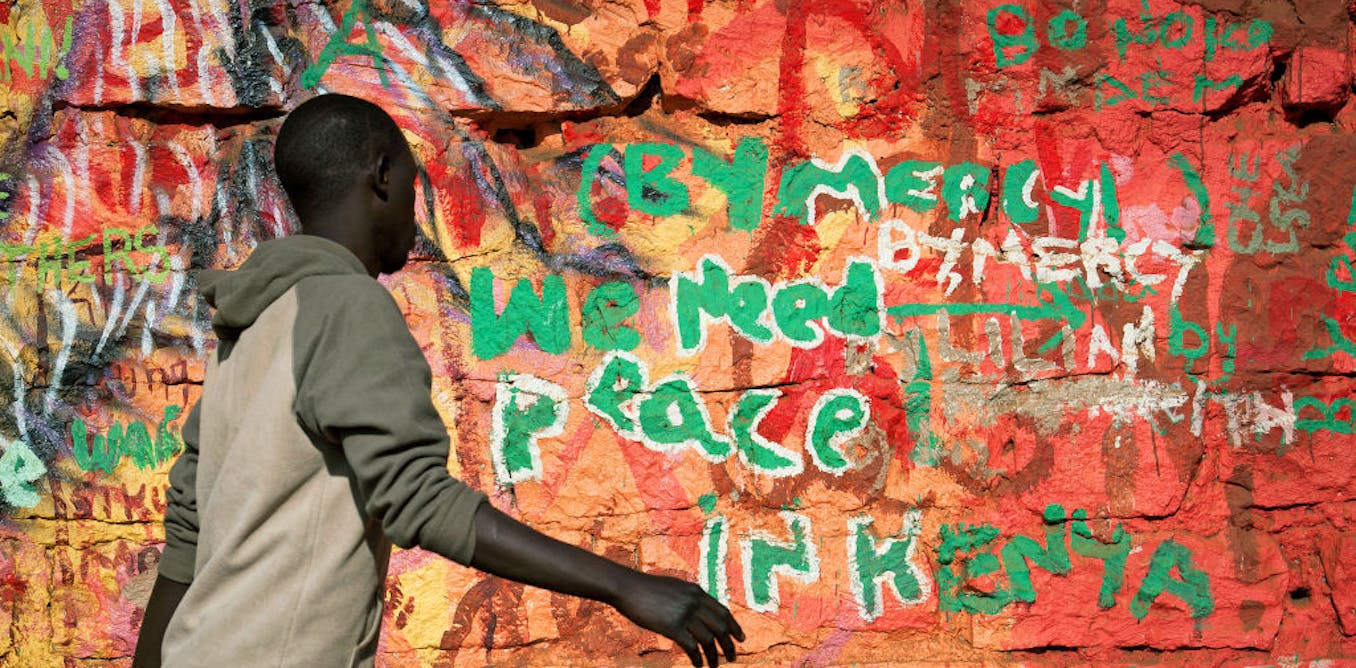

So, what does this mean in practice? Here I offer some of my work in Kenya as an example.

Peacebuilding in practice

In the run-up to Kenya’s August 2022 general election, the stakes were high. Experiences of post-election violence in previous election rounds, especially in 2007, were a vivid memory for many. Peacebuilders worried that conflict-prone communities could resort to violence again.

I trained about 30 peacebuilders on my model of communicative peacebuilding. I encouraged them to think about how they could bring divided groups together, engage them and prevent any outbreak of violence. A variety of ideas for initiatives came up and were implemented.

For example, one suggestion was to call on those who were involved in the violence in 2007-08 to speak about why they thought that looting was a good idea and how they had come to change their minds. Participants in former violence – as well as victims – would share their experiences to encourage others to reflect on the impact of violence.

Another example was to bring different ethnic groups together, and make videos in which they shared their biggest fears and greatest wishes regarding Kenyan society. The aim was to show that all tribes shared some of the same worries and concerns – from children’s education and future, to health and income. And that everyone in their own way cared for Kenya as a whole.

Another initiative aimed at combating hate speech on social media. Here, discursive civility helps deal with hate speech in calm and constructive ways rather than blaming or antagonising anyone.

Others thought of creating a magazine or newspaper online in which supporters of different parties and citizens with different views would write election news coverage together on behalf of one Kenyan society, rather than one’s chosen group.

Teamwork for a common goal

There’s a soap opera in Kenya which also illustrates communicative peacebuilding quite well. The Team Kenya, launched in 2009, is a drama about a fictional football tournament and how the players had to work as a team to win. They learned to get over differences in class, tribe, education and gender.

Intuitively, and as I show in my research, this soap opera shows how the three building blocks of peace can work.

But initiatives like these can only work if they are underpinned by discursive civility. Otherwise peacebuilding initiatives can be counter-productive and unintentionally increase conflict.

The post “What does it take to build a peaceful society? The 3 golden rules that make a difference” by Stefanie Pukallus, Professor of Public Communication and Civil Development, University of Sheffield was published on 12/05/2024 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply