There was a time when artists representing two of America’s biggest homegrown musical genres wouldn’t get a look in at the Grammys.

Hip-hop and house both have their origins in the 1970s and early 1980s – in fact, they recently celebrated a 50th and 40th birthday, respectively. But it was only in 1989 that an award category for “best rap performance” started recognizing hip-hop’s contribution to U.S. music, and house had to wait another decade, with the introduction of “best dance/electronic recording” in 1998.

At this year’s awards, taking place on Feb. 2, hip-hop and house artists will be among the most talked about. House duo Justice and Kendrick Lamar, a hip-hop superstar who incorporates elements of house himself, are among those looking to pick up an award. Meanwhile, a nomination for a collaboration between DJ Kaytranada and rapper Childish Gambino shows how artists from both genres continue to feed off each other.

And while both genres are now celebrated for their separate contributions to the music landscape, as a scholar of African American culture and music, I am interested in their commonality: Both are distinctly Black American artforms that originated on the streets and dance floors of U.S. cities, developing a devoted underground following before being accepted by – and transforming – the mainstream.

The pulse of the 1970s

The roots of hip-hop and house music both lie in the seismic shifts of the late 1970s, a period of sociopolitical unrest and electronic experimentation that redefined the possibilities of sound.

For hip-hop, this was expressed through the turntable manipulation pioneered by DJ Kool Herc in 1973, when he extended and looped breakbeats to energize crowds. House music’s innovators turned to the drum machine to create the genre’s foundational four-on-the-floor dance rhythm.

That rhythm, foreshadowed by Eddy Grant’s 1977 production of “Time Warp” by The Coachouse Rhythm Section, would go on to shape house music’s distinct pulse. The track showed how electronic instruments such as the synthesizer and drum machine could recast traditional rhythmic patterns into something entirely new.

This dance vibe – in which a base drum provides a steady four-four beat – became the heartbeat of house music, creating an enduring structure for DJs to layer basslines, percussion and melodies. In a similar way, Kool Herc’s breakbeat manipulation provided the scaffolding for MCs and dancers in hip-hop’s formative years.

Marginalized communities in urban centers like Chicago and New York were at the forefront of these innovations. Despite experiencing grinding poverty and discrimination, it was Black and Latino youth – armed with turntables, drum machines and samplers – who made these groundbreaking advances in music.

For hip-hop, this meant manipulating breakbeats from songs like Kraftwerk’s “Trans-Europe Express” and “Numbers” to energize b-boys and b-girls; for house, it meant extending disco’s rhythmic pulse into an ecstatic, inclusive dance floor. Both genres exemplified – and continue to exemplify – the ingenuity of predominantly Black and Hispanic communities who turned limited resources into cultural revolutions.

From this shared origin of technological experimentation, cultural resilience and creative ingenuity, hip-hop and house music grew into distinct yet globally influential movements.

The message and the MIDI

By the early 1980s, both genres had found their feet.

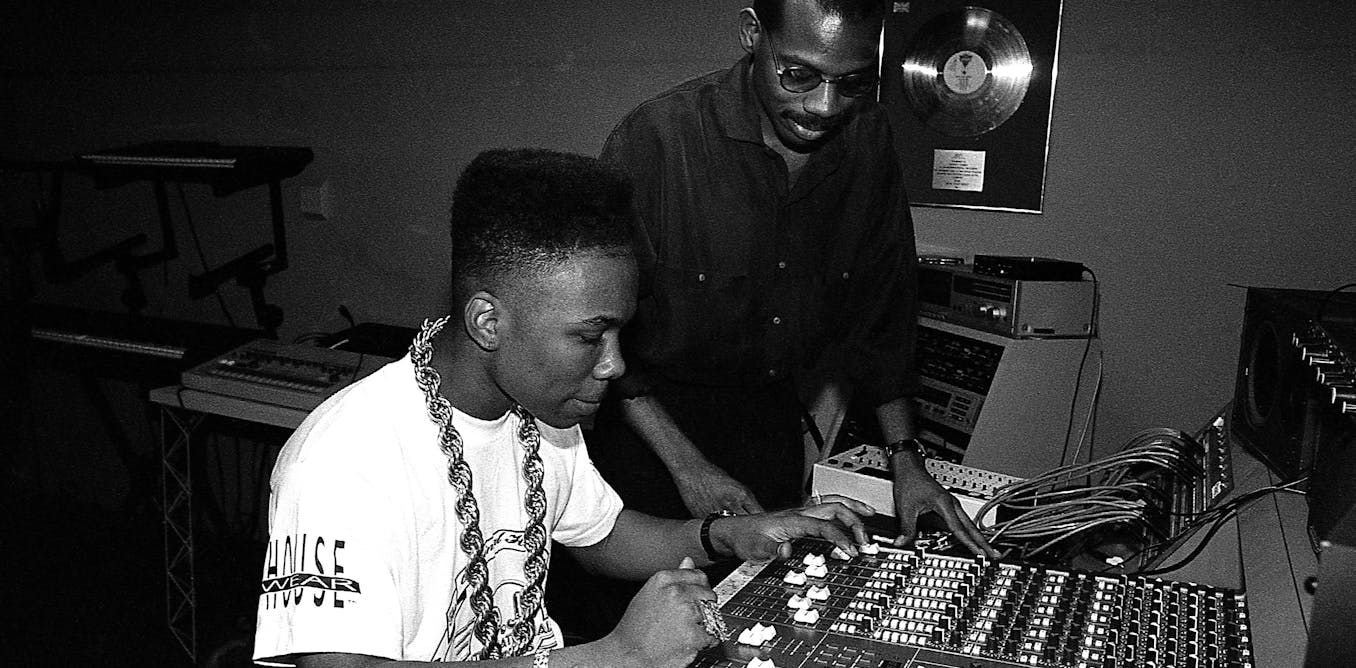

Hip-hop emerged as a powerful voice for storytelling, resistance and identity. Building on the foundations laid down by DJ Kool Herc, artists like Afrika Bambaataa emphasized hip-hop’s cultural and communal aspects. Meanwhile, Grandmaster Flash elevated the genre’s technical artistry with innovations like cutting and scratching.

Chris Walter/WireImage

By 1984, hip-hop had evolved from its grassroots beginnings in the Bronx into a cultural movement on the cusp of mainstream recognition. Run-DMC’s self-titled debut album released that year introduced a harder, stripped-down sound that departed from disco-influenced beats. Their music, paired with the trio’s Adidas tracksuits and gold chains, established an aesthetic that resonated far beyond New York City. Music videos on MTV gave hip-hop a new medium for storytelling, while films like “Beat Street” and “Breakin’” showcased the features and tenets of hip-hop culture: DJing, rapping, graffiti, breaking and knowledge of self – cementing its cultural presence, and presenting it to a world outside the U.S.

But at its core, hip-hop remained a voice for the voiceless that sought to address systemic inequities through storytelling. Tracks like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message” vividly depicted the reality of living in poor, urban communities, while Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” and Tupac Shakur’s “Keep Ya Head Up” became anthems for social justice.

Together these artists positioned hip-hop as a platform for resistance and empowerment.

Becoming a cultural force

Unlike hip-hop’s lyrical storytelling, house music focused on the physicality of rhythm and the collective experience of the dance floor. And as hip-hop moved away from disco, house leaned into it.

Italy’s “father of disco,” Giorgio Moroder, showed the way with his pioneering use of synthesizers in Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love.” Over in New York, Larry Levan’s DJ sets at Paradise Garage demonstrated how electronic instruments could create immersive, emotionally charged experiences as a club that centered crowd participation through dance and not lyrics.

By 1984, Chicago DJs Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy were repurposing disco tracks with drum machines like the Roland TR-808 and 909 to create hypnotic beats. Knuckles, known as the “Godfather of House,” transformed his sets at the Warehouse club into euphoric experiences, giving the genre its name in the process.

Jemal Countess/WireImage

House music thrived on inclusivity, served as a safe space for Black and Latino members of the LGBTQ+ communities at a time when hip-hop was severely unwelcoming of gay men. Tracks like Jesse Saunders’ “On & On” and Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body” celebrated freedom, love and unity, encapsulating its liberatory spirit, as rap music and hip-hop culture embarked on its mainstream journey with songs like Run DMC’s “Sucker M.C.s (Krush Groove)” and Salt-N-Pepa debuted their album “Hot, Cool, & Vicious.”

As with hip-hop, by the the mid-1980s house music had become a cultural force, spreading from Chicago to Detroit, to New York and, eventually, to the U.K.’s rave scene. Its emphasis on repetition, rhythm and electronic instrumentation solidified its global appeal, uniting people across identities and geographies.

Mainstays in modern music

Despite their differences, moments of crossover highlight their shared DNA.

From the late 1980s, tracks like Fast Eddie’s “Yo Yo Get Funky” and the Jungle Brothers’ “I’ll House You” merged house beats with hip-hop’s lyrical flow. Artists like Kaytranada and Doechii continue to blend the two genres today, staying true to the genres’ legacies while pushing their boundaries.

And technology continues to drive both genres. Platforms like SoundCloud have democratized music production, allowing emerging artists to build on the decades of innovations that preceded them. Collaborations, such as Disclosure and Charli XCX’s “She’s Gone, Dance On,” highlight their adaptability and enduring appeal.

Whether through hip-hop’s lyrical narratives or house’s rhythmic euphoria, these genres continue to inspire, challenge and transcend.

As the 2025 Grammy Awards celebrate today’s leading house and hip-hop artists and their contemporary achievements, it is clear that the legacies of these two genres are mainstays in the kaleidoscope of American popular music and culture, having come a long way from back-to-school park jams and underground dance parties.

The post “How hip-hop and house revolutionized music and culture” by Joycelyn Wilson, Assistant Professor of Ethnographic and Cultural Studies , Georgia Institute of Technology was published on 01/30/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply