In the hiatus that was COVID lockdown, the novelty of “staying put” had a peculiar grace and delight. To limit one’s trajectory to five kilometres meant homing in on the small and the local: the seasonal repetitions of a plant blossoming in a neighbour’s garden, new pale green leaves on trees, a smell of liquorice in the air heralding summer. I looked closer at the local and saw new things, or perhaps I saw old things with new eyes.

But with the reopening of airports – even in the face of inflated fares – I was planning my escape routes immediately. Carbon footprint aside: since COVID, I have been to France twice, to Italy, to Spain, to England, to Greece, to California, and to Indonesia, not to mention Adelaide, the Sunshine Coast and the Gold Coast.

I am gorging myself on travel, gluttonously, amassing memories and experiences, banking my travels like a spendthrift Scrooge. In the COVID era, travel became something to look forward to and look back on, an adventure put on hold. I now have a lust for experiencing what was, temporarily, forbidden and could conceivably be forbidden again. As much as I enjoyed discovering the charms of local wetlands, travel beckons with more allure than ever.

I began reading Literary Journeys – a compendium of what I will loosely call “travel novels” – the same day I went to hear Scottish historian William Dalrymple speak at the Palais theatre in Melbourne. I sat there in the Palais with my wine and popcorn and listened to Dalrymple talk, with contagious enthusiasm, of actual geographical journeys, but also of the intercontinental travel of ideas, stories, ways of being human – the Ramayana and Mahabharata, Buddhism and Hinduism.

Sated on the soft air of France, the crisp air of London, the sultry air of Indonesia, I could give myself up to imagined journeys. Air, I thought, is the medium of travel – moving through it, catching ideas on it.

If we can’t physically travel, stories of travel become our vicarious vessels. Reading is inherently transportive: a way of journeying on the wings of others without moving from the armchair (or, in my case, bed).

To read is to commune, from a place of solitude, with other readers who have entered the same imaginary terrain: to read a travel narrative is to walk (or drive or sail), in solitude, with other travellers whose steps have worn the path.

The pantheon

The editorial brief for Literary Journeys, required that all works selected for the book describe fictional journeys based on real locations. (There’s no Narnia here, no Middle Earth, no Phillip Pullman windows cut between worlds.) Literary Journeys is both a “travel companion” and “time machine”, chronologically arranged from 725 BCE to 2021, with several multi-century leaps; a chocolate-box sampler of travel fiction (albeit good chocolate with a high cocoa content and very little sugar).

Goodreads

Seventy-five books of “international fiction” are précised here, selected and discussed by 50+ contributors: charting fictional journeys that deliver their protagonists from places of innocence to those of darker understanding; journeys that skip merrily through places and experiences with novelty and adventure as their prime objective; and journeys that turn ineluctably back on themselves, have no rhyme or reason, no spiritual lesson to impart, or character growth involved.

Across water, on horseback and by carriage, by bicycle, on trains and planes and automobiles. In air balloons. On foot. There is movement across both geographical and psychological terrain.

As with any compendium of important literature – lists of the great – there is a risk of canonising certain works and leaving others in oblivion in such a project. Why this book’s inclusion, and not that?

Penguin

Two Australian novels are afforded a place in the pantheon: Tim Winton’s 2001 Dirt Music, with its Western Australian ghost-towns and asbestos and “cinematic” natural beauty, (according to Phoebe Taplin who writes on it). And Patrick White’s 1957 Voss, in which, as Robert Holden writes, the explorer Ludwig Leichhardt acts as “a metaphor for all men whose lives are unexplored desert and where suffering and humility are the preconditions of his spiritual quest”. Australia, due not least to its vastness, lends itself to literary commentary on both spiritual impoverishment and spiritual transcendence.

Penguin

There are the expected inclusions: Don Quixote; The Canterbury Tales; Around the World in 80 Days; Huckleberry Finn and Moby Dick; The Grapes of Wrath (I plan to read its Swedish equivalent Vilhelm Moberg’s 1949 The Emigrants, and its Irish equivalent, Joseph O’Connor’s 2002 Star of the Sea).

On the Road – “urtext of the James Dean decade” – obviously gets a place, as does Heart of Darkness (described here, diplomatically, by Kate McNaughton as “both anti-Imperialist pamphlet and relic of the colonial mindset”).

Unsurprisingly, there are fewer women writers than men represented in Literary Journeys, women only gaining the right of travel, or the right of unchaperoned travel, in fairly recent times. This is not to say, however, that the necessary journeys of migration have not been women’s journeys, and Literary Journeys recounts many stories of human displacement and desperation – as well as inhuman bureaucracy – that are particularly apposite in our own times of fracture and division.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The better-known western women writers appear – Harriet Beecher-Stowe, Mary Shelley, Virginia Woolf, Jeanette Winterson, Barbara Kingsolver – but also other towering female writers whose names may be less familiar to the Australian reader: Olga Tokarczuk, Audur Ava Olafsdottir, Ana Segher. Kim Thuy, Valeria Luisielli – these are authors I had not read or known of, but will find now, and will read.

It’s difficult to discuss the offerings of Literary Journeys without undertaking a chocolate-box sampler of my own, or, at least, without identifying holes I need to patch in my own reading.

Thomas Nashe’s 1594 The Unfortunate Traveller sounds like a hoot. Basho’s ninja-like 1702 Japanese journey in The Narrow Road to the Interior (a reference for Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North) is on my list; as is Sir Walter Scott’s 1818 The Heart of Midlothian; Gogol’s Dead Souls; and Wordsworth’s The Prelude.

Penguin

Laurence Sterne’s 1768 A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy had fallen out of fashion by the 19th century, but has since been admired by Virginia Woolf, Salman Rushdie and Italian Calvino. The vantage point of its main character Yorick, a travelling cleric, is particularly curious: he is “a nobody … interested in other nobodies: he writes about peasants, shopgirls, beggars”.

Travelling, for Yorick, provides connection not to the grand, the spectacular or even the picturesque but to the human quotidian of elsewhere.

Interior and exterior spaces

Peripatetic, peregrination, picaresque: these three semi-archaic “p” words find new relevance in Literary Journeys. All connote wandering, without purpose, without an imposed narrative arc, from episode to episode.

As in life itself, travel doesn’t arrange itself easily into a meaningful pattern; it has its highs and lows, its memorable moments, and a lot of time lost – or found – in transit. But novelists are pattern-makers, and journeys, for novelists, are a device to cast light on the human condition, as much as a means of getting characters in and out of scrapes, nudging elbows with the unsavoury and downright dangerous, delivering pleas for mercy or seeking lost family members.

Travel makes possible a re-invention of self, or a rediscovery of self. Be it backpacking on the smell of a greasy rag or travelling business class with a penthouse suite booked, travel allows space to unfold around the traveller (as well as creating conditions in which the traveller must sometimes fold up), to relinquish control, to be open to the unforeseen.

Being somewhere other, making the crossing to somewhere new, opens up both interior and exterior spaces: ideally, the traveller gains an enriched understanding of what it is to be human.

I travel to know more about myself and about others. But I also read to know more about myself and others: to experience other ways of being, other journeys, that I might bring into myself.

Penguin

In this way old classics gain from fresh appraisal, new eyes and ears. Nicholas Lezard describes Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe as “an allegory of Nonconformism” in which a loosening, a rethinking of the eponymous character’s received moral imperatives occurs.

When Robinson Crusoe witnesses cannibalism he “realises that not only do the cannibals not think they are doing wrong, but that he is not one to judge.” In this way, travel creates difference-tolerance, an ability to empathise, or at least co-exist with, what has been culturally imprinted as morally repugnant.

Observations about the metaphorical link between travel and narrative and the human condition abound in Literary Journeys, most notably for me in Sarah Mesle’s précis of Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

In Dracula, writes Mesle, the characters’ trips between London, Amsterdam and Transylvania

mimic the course of blood: circulation holds more sway than destination. The characters circulate like blood because blood is Dracula’s vehicle, and for most of the story they are trapped in Dracula’s will […] The journeys in Dracula show to the reader what it means to be human: that it can be difficult to tell the difference between moving and being trapped: that there are forces within us, moving us, which we may learn to track but can never completely control.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Travel is not always presented as an ineluctable good, commensurate with character development, with learning and growth and self-expansion.

In discussing Paul Bowles’s The Sheltering Sky, Katie da Cunha Lewin considers the difference between the tourist and the traveller, and the traveller’s conceptualisation of the journey as life rather than a reprieve from life.

Is the elevation of “travel” as superior to “tourism” existentially justifiable? Da Cunha Lewin writes that

Bowles’s book asks many questions about the journey away from somewhere, so that, rather than a novel about the process of travel, it is really about the fact that ceaseless travel can become a way of avoiding the real problems and complexities of life.

A tourist takes off with an itinerary and bookings; a traveller departs with a vague route and perhaps idealistic notions of what they will find. But both are looking for experiences, whether existential or picturesque.

Travel can also be a means of escapism and avoidance, rootlessness and superficial connectedness.

Connecting the synapses

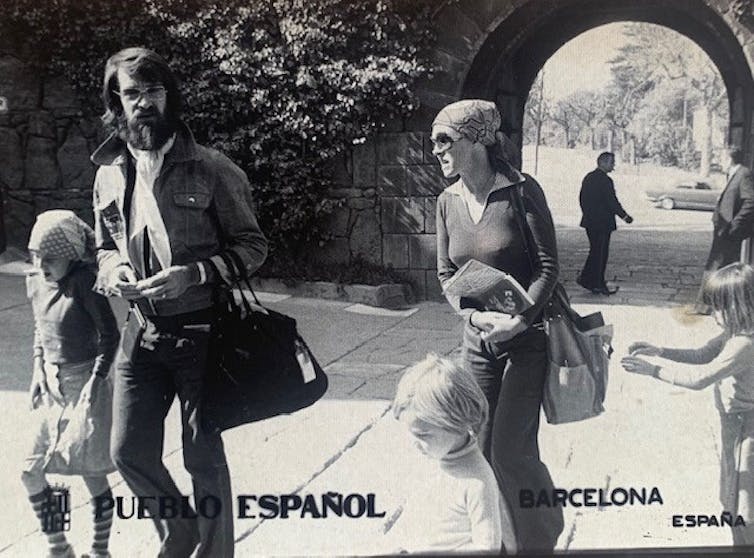

There is little like the excitement of an impending journey. As a very young child, in the 1970s, I travelled overseas with my family on a six-month campervan trip – my parents’ first trip to Europe. We visited England, Scotland, Greece and Italy; Spain, the former Yugoslavia, and Germany and then, the reward held out to us for good behaviour at the end, Disneyland in LA.

Author provided, CC BY

What was this “overseas”? I imagined the far side of a broad river, swept with deep green willow trees. The kind of impenetrable forest you’d have to cut through with a knife or sword. So exciting. In fact, so excited was I that I stood up at my school assembly, three weeks into Grade Prep, and announced my impending journey to the whole school, much to the mirth of my peers and my teachers.

And when I returned from that six-month journey, fishing the untouched Grade Prep readers from the bottom of my orange suitcase, I discovered that miraculously, without any effort on my part, I could read. Travel, I have since concluded, connects the synapses.

But for travel to be meaningful, it needs to have a hearth and home to return to. I know I experience almost as much excitement returning home after a period of travel as I do leaving home in the first place: this is, I think, a familiar phenomenon.

Literary Journeys is a book I will return to and mine in future for its robust literary recommendations. My first port of call will be Jerome K. Jerome’s 1889 Three Men in a Boat: a winsome adventure where the stakes are not high, the dangers nonexistent and the worst that can happen is that an unopenable pineapple tin will laugh at you with a “mocking grin”, and refuse to obey the ministrations of a can opener.

Escapism perhaps, but hopefully an antidote to the ills, pains, and pessimism of the present moment.

My reading road lies before me, newly refreshed, newly paved.

The post “a reinvention of self – the pleasure of literary journeys” by Edwina Preston, PhD Candidate, Creative Writing, The University of Melbourne was published on 02/06/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply