Bird beaks come in almost every shape and size – from the straw-like beak of a hummingbird to the slicing, knife-like beak of an eagle.

We have found, however, that this incredible diversity is underpinned by a hidden mathematical rule that governs the growth and shape of beaks in nearly all living birds.

What’s more, this rule even describes beak shape in the long-gone ancestors of birds – the dinosaurs. We are excited to share our findings, now published in the journal iScience.

By studying beaks in light of this mathematical rule, we can understand how the faces of birds and other dinosaurs evolved over 200 million years. We can also find out why, in rare instances, these rules can be broken.

When nature follows the rules

Finding universal rules in biology is rare and difficult – there seem to be few instances where physical laws are so pervasive across all organisms.

But when we do find a rule, it’s a powerful way to explain the patterns we see in nature. Our team previously discovered a new rule of biology that explains the shape and growth of many pointed structures, including teeth, horns, hooves, shells and, of course, beaks.

This simple mathematical rule captures how the width of a pointed structure, like a beak, expands from the tip to the base. We call this rule the “power cascade”.

After this discovery, we were very interested in how the power cascade might explain the shape of bird and other dinosaur beaks.

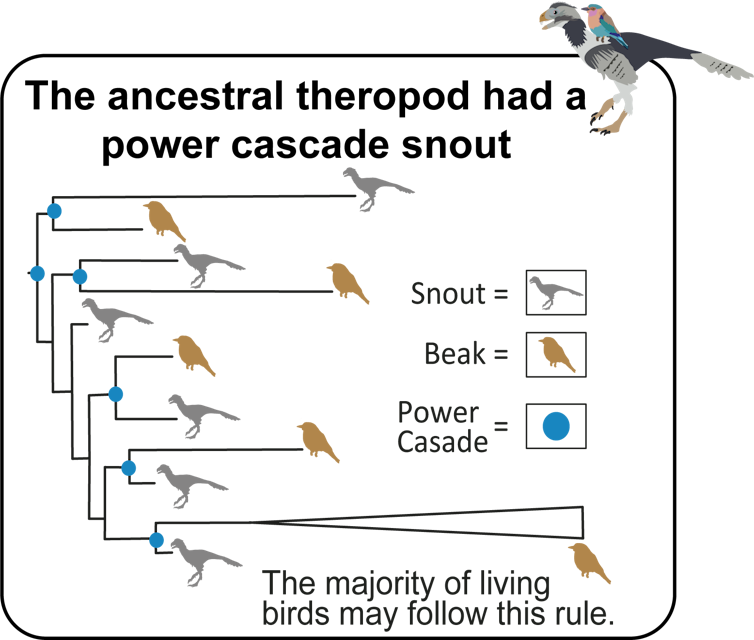

Garland et al., iScience 2025

Dinosaurs got their beaks more than once

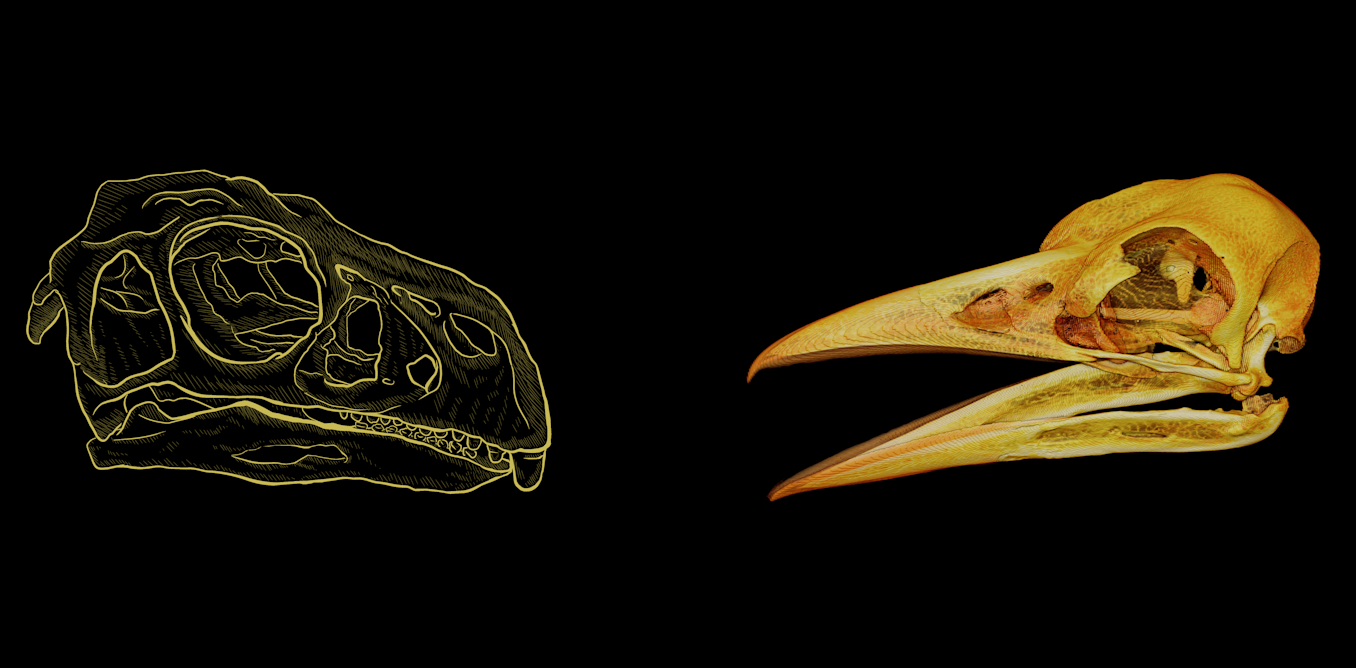

Most dinosaurs, like Tyrannosaurus rex, have a robust snout with pointed teeth. But some dinosaurs (like the emu-like dinosaur Ornithomimus edmontonicus) did not have any teeth at all and instead had beaks.

In theropods, the group of dinosaurs that T. rex belonged to, beaks evolved at least six times. Each time, the teeth were lost and the snout stretched to a beak shape over millions of years.

But only one of these impeccable dinosaur groups survived the mass extinction event 66 million years ago. These survivors eventually became our modern-day birds.

The early bird catches the rule

To investigate the power cascade rule of growth, we researched 127 species of theropods. We found that 95% of theropod beaks and snouts follow this rule.

Using state-of-the-art evolutionary analyses through computer modelling, we demonstrated that the ancestral theropod most likely had a toothed snout that followed the power cascade rule.

Excitingly, this suggests that the power cascade describes the growth of not just theropod beaks and snouts, but perhaps the snouts of all vertebrates: mammals, reptiles and fish.

Garland et al., iScience 2025

The rule followers and breakers

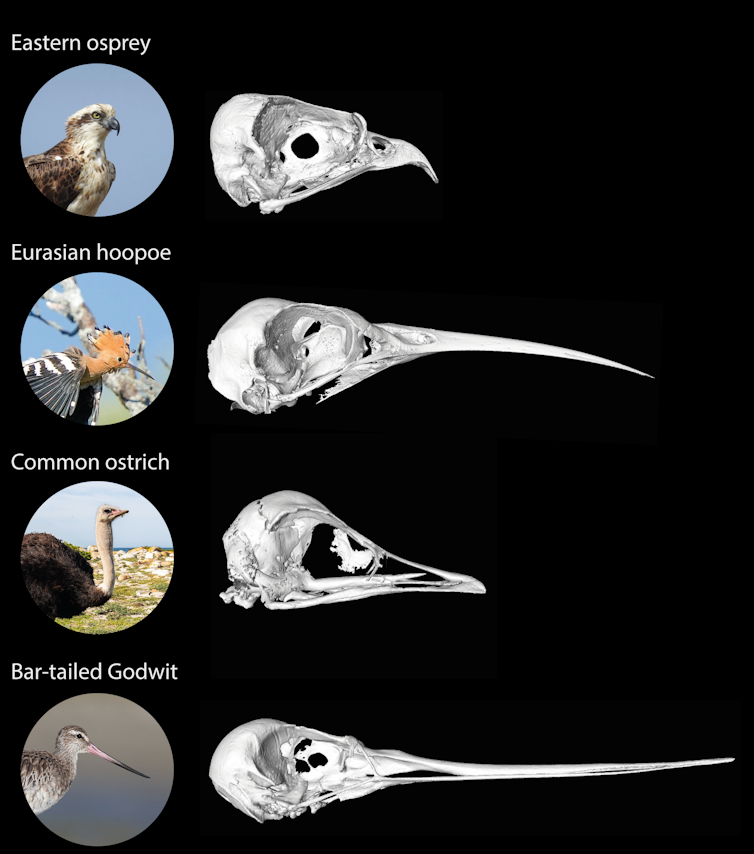

After surviving the mass extinction, birds underwent a period of incredible change. Birds now live all over the world and their beaks are adapted to each place in very special ways.

We see beak shapes for eating fruit, netting insects, piercing and tearing meat, and even sipping nectar. The majority follow the power cascade growth rule.

Eastern osprey by Phill Wall (modified, CC BY 2.0), Eurasian hoopoe by Giles Laurent (modified, CC BY-SA 4.0), common ostrich by Diego Delso (modified, CC BY-SA 4.0) and bar-tailed godwit by JJ Harrison (modified, CC BY-SA 4.0).

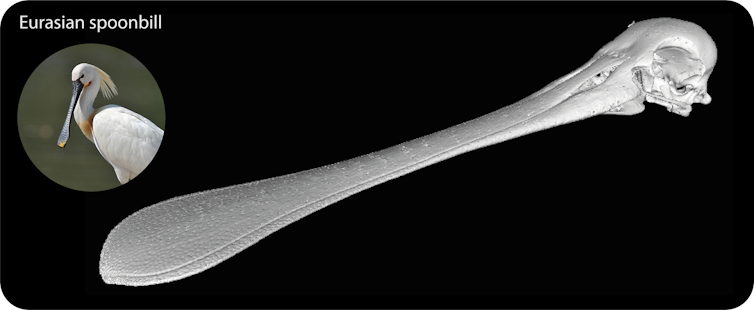

While rare, a few birds we studied were rule-breakers. One such rule-breaker is the Eurasian spoonbill, whose highly specialised beak shape helps it sift through the mud to capture aquatic life. Perhaps its unique feeding style led to it breaking this common rule.

Eurasian spoonbill by Swardeepak (modified,CC BY-SA 4.0)

We are not upset at all about rule-breakers like the spoonbill. On the contrary, this further highlights how informative the power cascade truly is. Most bird beaks grow according to our rule, and those beaks can cater to most feeding styles.

But occasionally, oddballs like the spoonbill break the power cascade growth rule to catch their special “worms”.

Now that we know that most bird and dinosaur beaks follow the power cascade, the next big step in our research is to study how bird beaks grow from chick to adult.

If the power cascade is truly a foundational growth rule in bird beaks, we may expect to find it hiding in many other forms across the tree of life.

The post “A secret mathematical rule has shaped the beaks of birds and other dinosaurs for 200 million years” by Kathleen Garland, PhD Candidate, School of Biological Sciences, Monash University was published on 04/20/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply