Your neighborhood is home to all sorts of amazing animals, from racoons, squirrels and skunks to birds, bugs and snails. Even if you don’t see them, most of these creatures are leaving evidence of their activities all around you.

Paw prints in different shapes and sizes are clues to the visitors who pass through. The shapes of tunnels and mounds in your yard carry the mark of their builders.

Even the stuff animals leave behind, whether poop or skeletons, tells you something about the wilder side of the neighborhood.

Snowmanradio/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

I’m a zoologist and director of the Hefner Museum of Natural History at Miami University of Ohio, where we work with all kinds of wildlife specimens. With a little practice, you’ll soon notice a lot more evidence of your neighborhood friends when you step outside.

What makes those animal tracks?

You can learn a lot from a nice, crisp paw print.

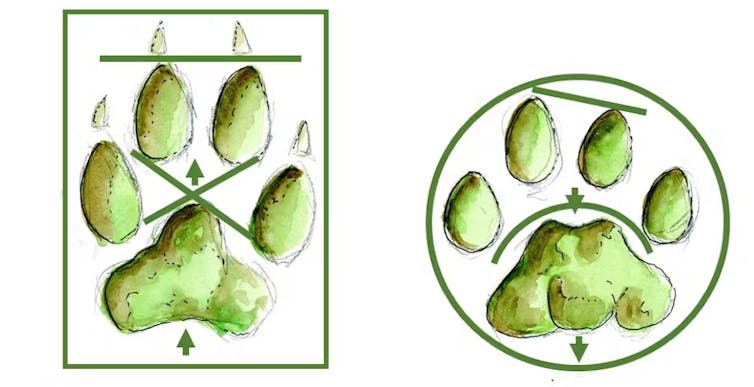

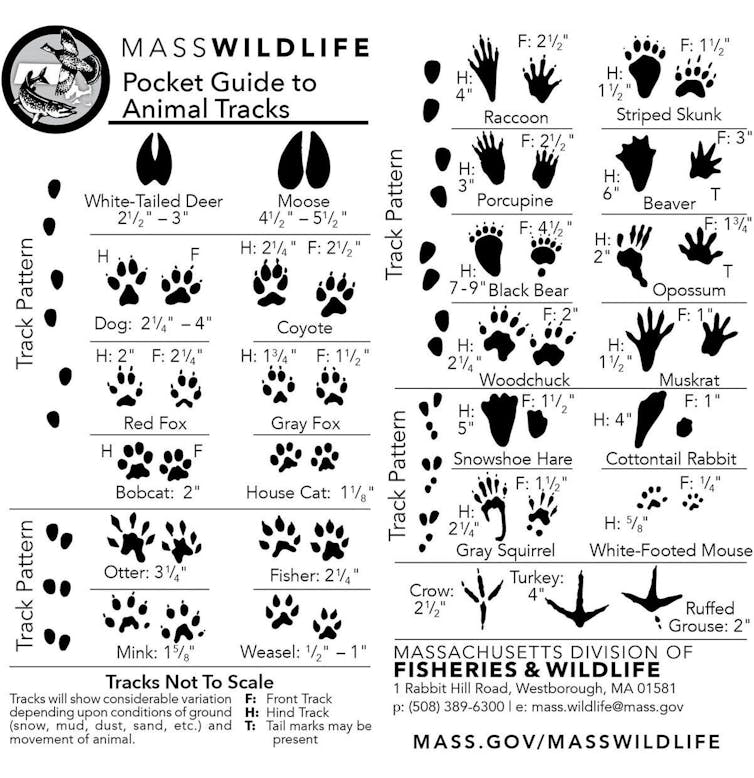

The dog family, including coyotes and foxes, can be differentiated from the cat family by the shape of their palm pads — triangular for dogs, two lobes at the peak for cats.

Steven Sullivan, CC BY-NC-ND

Both opossums and raccoons leave prints that look like those of a tiny human, but the opossum thumb is held at nearly right angles to the rest of the fingers.

Steven Sullivan

Not all prints are so clear, however.

Invasive rats and native squirrels have prints that often look pretty similar to each other. Water erosion of a skunk print left in mud might connect the toe tips to the palm, making it look more like a raccoon. And prints left in winter slush by the smallest dog in the neighborhood can grow through freezing and thawing to proportions that make people wonder whether wolves have returned to their former haunts.

There are good reference books where you can learn more about track analysis, and it can be fun to go down the rabbit hole of collecting and studying prints.

Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife

Clues from holes and other animal excavations

Often, it’s easiest to figure out which animal left a paw print by correlating its tracks with other evidence.

If what look like squirrel prints lead to a hole in the ground, then it wasn’t a tree squirrel. Stuff a handful of leaves or newspaper in the hole. If it gets pushed out during the day, the hole is probably inhabited by a ground squirrel, such as a chipmunk. But if the plug is pushed out at night, you probably have a rat.

I once noticed a faint trail in the soil near my porch. Using the hole-stuffing method, I determined that something spent most days under the wooden stairs that people constantly, and often loudly, traversed. When I was pretty sure my newly discovered neighbor was home, I used a mirror and flashlight to investigate the opening without exposing myself to a protective resident. Sure enough, there was a cute little skunk staring back at me.

Skunks, and many other local animals, often leave obvious excavations in lawns.

Lawns are biological deserts where few species can live, but those that can survive there often reach high numbers. Lawn grubs – the milk-white, C-shaped caterpillars of a few beetle species – particularly love the lack of competition found in a carpet of grass. Polka dots of dead thatch are one sign of these grubs, but if you have a biodiverse neighborhood, many animals will consume this high-calorie treat before you ever notice them.

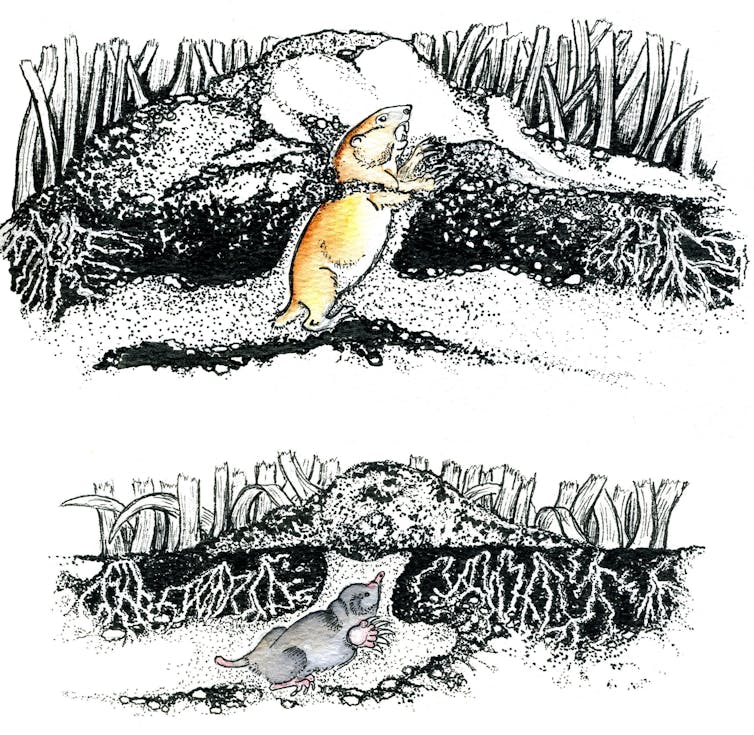

Skunks and raccoons will dig up each grub individually, leaving a small hole that healthy grass can refill quickly. Moles – fist-size insectivores more closely related to bats than rodents – live underground where they virtually swim through soil, leaving slightly raised trails visible in mowed lawns. In spring and fall, moles make volcano-shaped mounds with no visible opening.

Steven Sullivan

Gophers, on the other hand, are herbivorous rodents – they eat plants rather than grubs. They also leave tunnels and mounds, but the tunnels are usually very visible and their mounds are crescent-shaped, often with a visible opening.

Voles, not to be confused with moles, are also herbivorous rodents. They’re mouse-size, with tiny, furry ears and short tails. They may dig small holes, but more obviously they leave thatch-lined runways on the surface.

Steven Sullivan

Even the cicadas singing loudly in the trees in my yard this summer left pinky-size holes in the ground as they emerged 17 years after hatching. The boom-bust cycle of cicadas has brought more moles, squirrels and birds to my neighborhood this year to munch on the nutrient-rich insects.

The evidence left behind, including poop

Where there is food, there is poop. Though the subject of feces is taboo among polite human society, it’s a fundamental, though understudied, communication method for many mammals.

Think about a dog marking its territory. Sometimes it seems they can’t go for more than a few feet before reading the pee-mail left on every prominent post. Urine, feces and gland oil act like social media posts, conveying each individual’s identity, health, height and reproductive status, the availability and quality of prey, and the extent of their territory.

Though most of the smell communication is lost on humans, the contents of the feces can tell a lot about the inhabitants of a neighborhood.

Domestic dog poop is usually just a big, homogeneous lump because they eat processed food, but wild canid feces is often full of bones and fur. Coyote feces is usually lumpy and larger than fox feces, which has pointy ends. Once it has weathered a bit, it’s easy to break open to find identifiable remains such as vole, rat and rabbit. Use care when inspecting feces, since it may transmit parasites.

Depending on time of year, the contents and shape of feces can vary considerably. Raccoon feces lacks the pointy ends and is often filled with seeds, but wild canids may eat lots of seeds, too. Deer feces is usually small, fibrous pellets, but those pellets may form clumps.

If you are lucky, you might find a pellet of bone and fur regurgitated by an owl near the base of a tree. Carefully break it apart and there’s a good chance you’ll find the skull of a vole or rat.

Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren, CC BY

Look closely at living and dead trees to find evidence of even smaller neighbors. A fine, uniform, granular sawdust pushed from tiny holes in bark can indicate beetle larvae feces, or “frass.” A large mass of frass at the base of a tree likely indicates carpenter ants.

In contrast to dusty frass, aphids slurp sap so rich in sugar that their feces coats surrounding surfaces in, essentially, maple syrup.

All of these insects attract many species of birds. Woodpeckers are hard to miss as they loudly hammer holes into trees. But don’t blame them for tree decline – they eat the things that are killing the tree.

Look for dead trees

Dead trees are a key feature of wildlife habitat, like a bus stop, and host different occupants throughout the day and over the year.

Eric Phelps via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

For example, a tree buzzing with cicadas in my yard this summer is quite healthy but has one big, dead branch that has been an important way station for wildlife over the past 20 years.

A decayed cavity at the base of the branch is polished smooth with the activity of generations of squirrels, while the tip is a favorite perch of all the neighborhood birds. By night, it is visited by a great horned owl, who, I somewhat sadly note, may be scanning for my porch skunk.

Decomposers: The neighborhood cleaning crew

This brings us to the decomposers. Animal carcasses are evidence of the neighborhood’s wild population, too, but they typically don’t last long. Insects make quick work of dead animals, often consuming the soft parts of a carcass before it is even noticed by humans.

Long after most activity around the carcass has ceased, exoskeletons left behind by the decomposers will remain in the soil. Dermestids, including the carpet beetles often found in our homes, leave fuzzy larval exoskeletons. Fly pupae look like brown pills. And sometimes adult carrion beetles keep a home underneath partially buried bones for years.

VPaleontologist/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Benoit Brummer/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Earthworms, feasting on nutrient-soaked soil, may leave a squirt of mud like a string of hot glue, while ants will leave piles of uniformly sorted sand. Snails will visit carcasses periodically to eat the bones, leaving trails that sparkle like thin, impossibly long ribbons in the morning sun.

From snails to skunks, squirrels to cicadas, most of our neighbors are quiet and seldom interact with us, but they play important roles in the world.

As we get to know them better, through their digging, eating and decomposing, and sometimes by watching them in action, we can better understand the animals that make our own lives possible and, maybe, understand ourselves a little better, too.

The post “How to identify animal tracks, burrows and other signs of wildlife in your neighborhood” by Steven Sullivan, Director of the Hefner Museum of Natural History, Miami University was published on 09/29/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply