Sophie Mgcina, composer, educationist and performer, gazes out from the page, uncompromising and direct. She’s just swung around from the piano to face us; behind her, a score sits open. It’s 1993, and she’s been telling journalist Z.B. Molefe, “I had to work like 10 black women to get where I am today.” But if she hadn’t said it, photographer Mike Ndumiso Mzileni’s accompanying image would have stated it loud and clear.

Respected elder statesman of press photographers Mzileni has died at the age of 80, after a series of debilitating ailments, but not before an exhibition in January in Johannesburg had finally brought together both facets of his long career: news photography that captured history, and music photography where artists had the visual space to be who they really were.

Photojournalism

Mzileni was a photojournalist described by one reporter as “one of the last of the Drum-era soldiers credited as black journalism’s pathfinders”. He began working in the 1970s, during the turbulence of South Africa’s apartheid years. He documented black life under white minority rule, one of the photographers who captured the Soweto Uprising of 1976.

Ndumiso Mzileni was born in Stutterheim in the Eastern Cape on 16 January 1942. His work featured in publications including The World, Drum, the Rand Daily Mail and the Sunday Times. His longest stint was at City Press, which he joined on its establishment in 1982, rising to become chief photographer by his retirement in 2000.

Tributes were not slow to pour in: just about every young photographer who encountered him had memories of his kindness and support for their own careers, of the high newsroom standards he set and of the steadfast Africanist politics that informed his lens. “A camera is more powerful than an AK47,” he admonished; be responsible in how you employ it.

The music photos

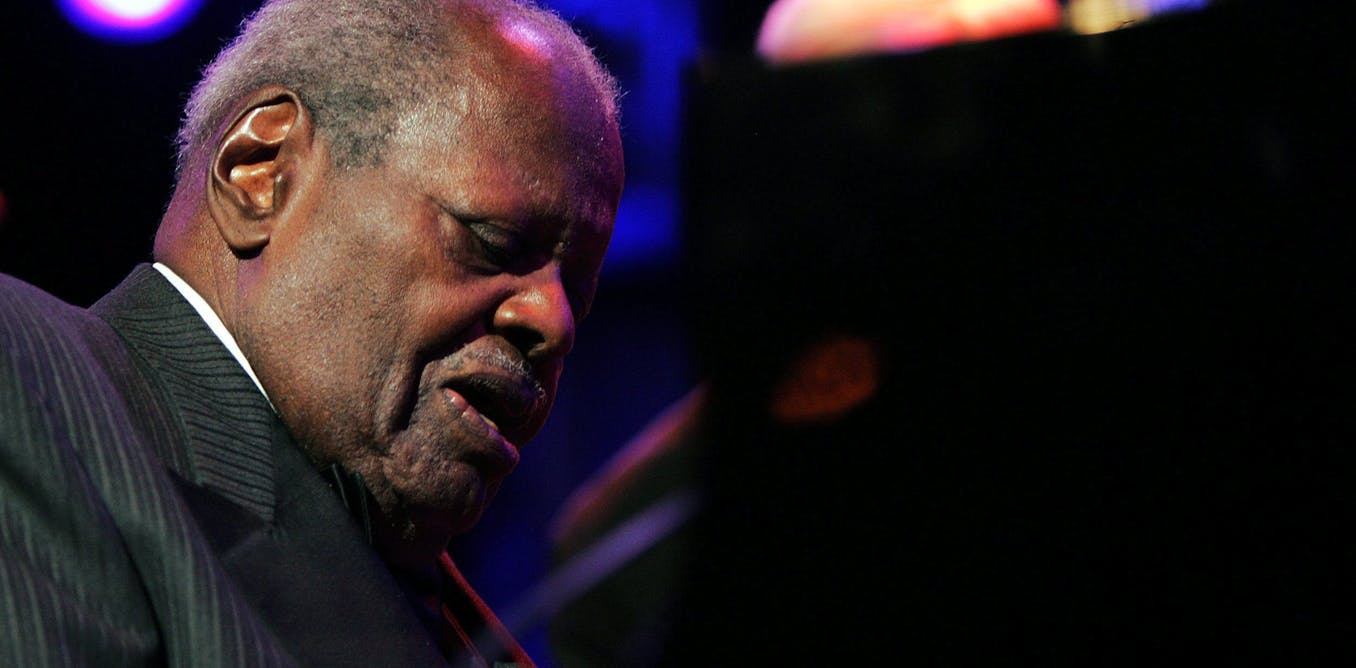

For jazz fans, it is Mzileni’s images of music-making and musicians, collected in two books, A Common Hunger to Sing (the source of that Mgcina image) and All That Jazz, which bring home most powerfully the skill and insight we have lost. Alongside his vibrant performance images, Mzileni’s jazz portraits in particular established a standard and an approach that inspired and influenced younger counterparts such as Siphiwe Mhlambi.

Kwela Books

Philosopher Susan Sontag asserted, “The painter constructs, the photographer discloses.” In other words, the truth of a photographic subject is there already; the photographer’s art is finding it and expressing it as an image so viewers can find it too. Photographers make, not simply find and “take” photographs. Their choices about a subject’s setting and pose, and how a shot is framed and lit, can reveal or obscure that subject’s truth, and sometimes even (accidentally or deliberately) convey something else entirely.

The worst of music photography – today’s unskilled point and shoot fan shots, which editors too often use instead of employing specialist, skilled photographers – doesn’t tell us much except what an artist was wearing, how wide their mouth gaped behind a mic or how dazzling the stage lights were.

But that was not Mzileni’s enterprise. The discipline of black and white photography like his takes away the easy dazzle of stage lights and sequined costumes that a full-colour image can ride on. It makes intelligent choices about framing and lighting even more crucial.

Women of jazz

We see clearly how powerful those choices can be in the portraits of female artists Mzileni created for A Common Hunger to Sing.

There’s a democracy between the artist in front of the camera and the one behind it in how Mzileni presents these women. Some have chosen to wear African finery (Mara Louw). Some, such as veteran Snowy Radebe, sit in their best chair, in their best jacket and neat beret: a respected matriarch of family and church. Others, like Mgcina, Lynette Leeuw, Nothembi Mkhwebane and Sathima Bea Benjamin, present themselves in the context of their music. Mgcina has that piano; Leeuw cradles her saxophone; Mkhwebane proffers her guitar ahead of her; Benjamin fans out some of her albums. Some smile; some look thoughtful, challenging, solemn or sad.

And Mzileni’s lens doesn’t treat any of this as incidental to zoom in for the big shiny grin that has become the cliche of photographing female singers. Every fold and print detail of Louw’s attire, for example, matters for that image, because her vocal identity is as a consummate stylist of song. The clearly-lit experience lines on the faces of stage veterans reinforce their authority and stature: the portrait of Dorothy Masuku is distilled down to the fierce intelligence of her expression, and the working hands that wrote her songs.

Mzileni was fond of chiaroscuro and used it well: light illuminates the joy of those who have told happy tales in Molefe’s interviews; shadow underlines the regrets and frustrations of others. The full-page portrait of each artist does not just complement the full-page interview it sits opposite; it underlines but also enriches each story. The shared authorial credit on the book’s cover is more than justified.

Another master photographer, the Frenchman Henri Cartier-Bresson, declared:

It is an illusion that photographs are made with the camera … they are made with the eye, heart and head.

With Mike Mzileni’s passing, we have lost the eye, heart and head of a titan of South African music portraiture.

This article appeared in an earlier form at the author’s web page.

The post “Legendary Mike Mzileni captured South Africa’s history and also its musical stars” by Gwen Ansell, Associate of the Gordon Institute for Business Science, University of Pretoria was published on 06/07/2022 by theconversation.com