Have you ever noticed that time slows down while you’re traveling somewhere new yet flies by when you’re steeped in your everyday routine? Doesn’t this seem to contradict the old saying “time flies when you’re having fun”? Although scientists generally agree on the basics of how we see, hear, think, and plan, time perception largely remains a mystery, with little consensus on how it’s processed in the brain.

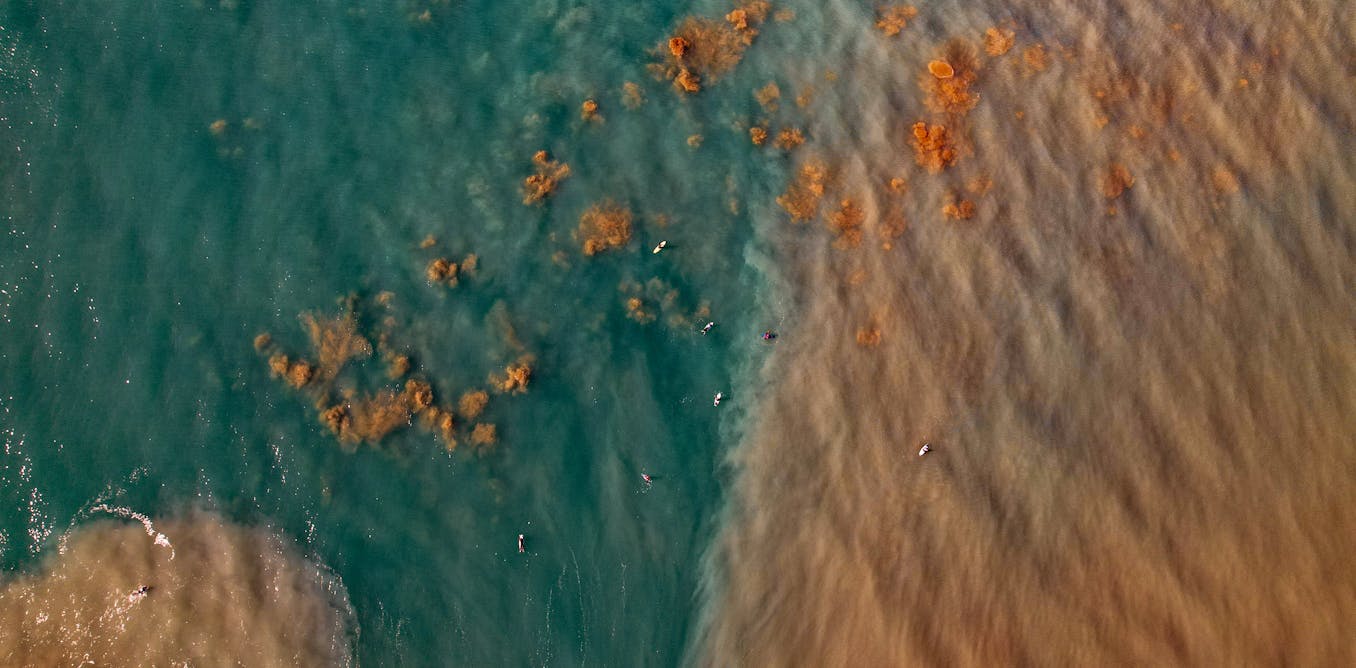

Recently, some researchers have been turning toward the body — the heart, specifically — to explore how we subjectively process time. Their findings not only solve part of the mystery but also suggest that we can influence our sense of time by changing the “embodiedness” of our daily habits — in other words, how aware we are of our bodily signals during an experience.

It’s well-established that our sense of time, including remembered time, changes according to how we experience events. One classic example is the oddball effect, a phenomenon captured in experiments where the presentation of a novel stimulus is perceived to last longer than stimuli presented routinely (referred to as “stimulus duration”). Another is the flashbulb memory effect: a vivid, long-lasting memory about a shocking event.

Age and habits also influence how we perceive the passage of time.

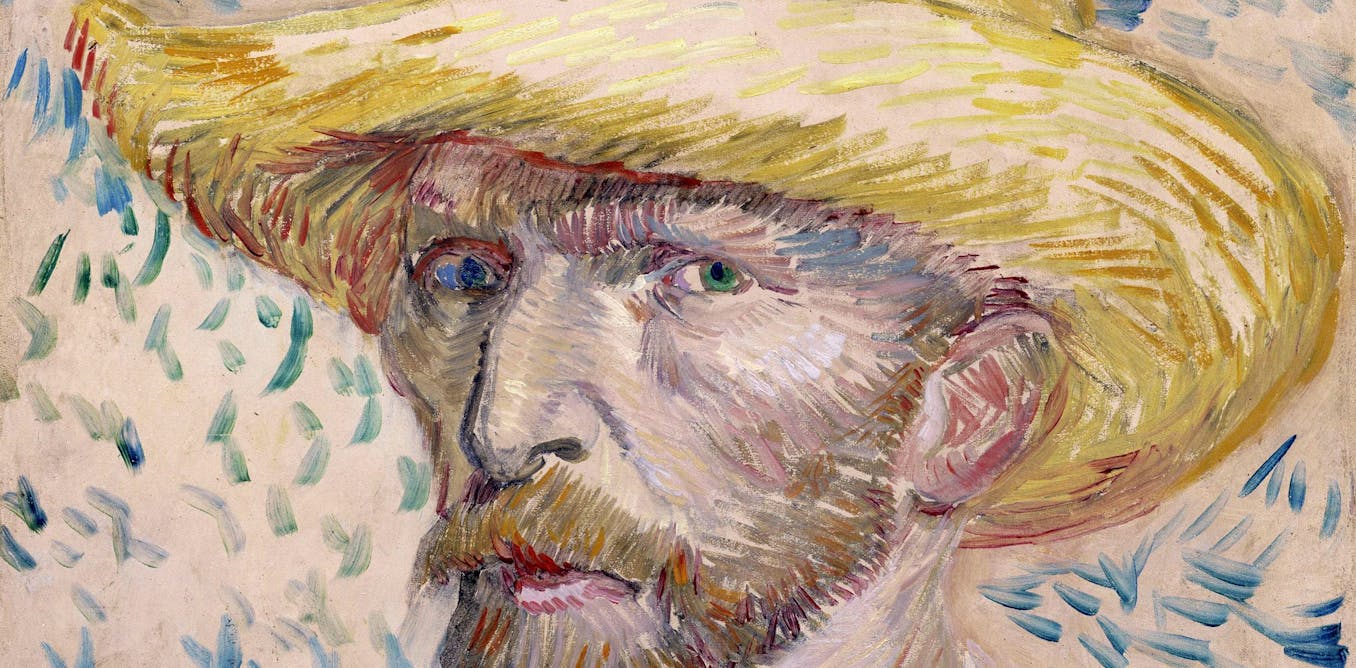

“As we grow older, subjective time accelerates as routine increases; a fulfilled and varied life is a long life,” Marc Wittmann, a psychologist and time researcher at the Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health in Freiburg, Germany, wrote in his 2016 book Felt Time.

But what mechanism might underlie these effects?

How the brain keeps time

Wittmann’s work builds off of a theory of time developed by the late neuroscientist Bud Craig, who believed that we perceive the passage of time through an awareness of bodily feelings. Craig linked our perception of time to how the brain interprets ongoing physiological changes in the body, like heart rate. These continuous signals are processed by a brain region known as the insular cortex, which is crucial for integrating these bodily sensations.

To test Craig’s theory, Wittmann conducted fMRI research where participants were asked to listen to a tone and, once it stopped playing, press a button for the duration they believed the tone had lasted. The results showed gradual increases in activity within the insular cortex that correlated with the length of a stimulus. This means that as a timed event began, there was a noticeable rise in brain activity within the insular cortex, which sharply dropped off once the event concluded. This pattern was observed in both the phases of encoding memories (in the dorsal posterior part of the insula) and recalling them (in the anterior part of the insula).

In other words, the results suggest that the insular cortex may act as the brain’s stopwatch, helping to track the duration of our experiences.

“These studies were perhaps the first to explicitly disclose theoretically and at the same time discuss empirical findings of insular cortex activation as a mechanism for explaining the estimation of duration,” Wittmann told Big Think. “The publication was definitely the first to document a potential accumulation-type function in the insular cortex which was correlated with the processing of time intervals, fitting Bud Craig’s theory.”

Research is mounting to support these findings. Last year, two research groups (Naghibi et al. 2023; Mondok and Wiener 2023) published meta-analyses from over 100 neuroimaging studies identifying brain structures related to the sense of time. The brain regions most consistently activated after rigorously designed control tasks were the supplementary motor area (SMA) and the insular cortex. These two brain regions, which are functionally connected, were shown to be activated across different time scales, independent of modality.

“Conceptually, time perception is driven by sensorimotor (SMA) timing processes, or body action, and by signal processing of body states (insula),” Wittmann says.

The role of bodily signals

But to call the SMA and insular cortex “brain regions for time” would be to miss the point. According to Craig, Wittmann, and others, it’s the interaction between the brain and the activity of bodily signals themselves — such as heartbeat — that allows for a sense of time to arise at all.

“There is no sense organ for time in the brain,” Irena Arslanova, a postdoctoral researcher who studies interoception at Royal Holloway, University of London, told Big Think. “Instead, perceived duration likely arises from the way in which the brain takes in and processes sensory input, which is ultimately shaped by fluctuations within visceral organs like the heart, the lungs, the gut.”

Arslanova’s own work has found that time perception changes with the rhythms of the heart.

“When something coincides with the heart’s contraction, its perceived duration gets contracted, in contrast to when it coincides with the heart’s relaxation. So, we showed that the momentary state of the heart has a causal influence over how duration was experienced.”

So far, due to the ease of measuring it, Arslanova’s focus has been on the heart and not respiration or the gut, but her intuition is that it will all be connected.

“There are intuitive connections between visceral fluctuations,” she said. “We can slow down our breathing to slow down the beating of our heart, and perhaps this would slow down the passage of time. But more research is needed to ascertain that scientifically.”

What’s clear is that whatever neural mechanisms give rise to the perception of time must be influenced by interoception (brain-body communication). It’s still an open question how this might work, but it suggests we have more control over our experience of time than we might suppose. Wittmann offers that subjective time can be indirectly manipulated by more present awareness, which yields more memory content and, in turn, affects time perception.

“In retrospective time perception, the more emotional memory and changes in remembered events, the longer subjective duration,” he says. “The more (unconscious) routine (autopilot mode), the faster the passage of a given time interval in retrospect.”

Wittman’s work has shown that more mindful individuals with more body-focused meditation experiences judged the previous week and month to have lasted longer.

“Being more aware (mindful) will lead to more memorized events and in turn to longer time estimates when looking back.”

So if you want that holiday to seem a little longer, take it in, one embodied moment at a time.

This article How does the brain keep time? It may rely on the body is featured on Big Think.

The post “How does the brain keep time? It may rely on the body” by Saga Briggs was published on 02/15/2024 by bigthink.com