It’s 2024 and fantasy author George R.R. Martin has officially spent 12 years working on The Winds of Winter, the long-awaited sixth installment in the series that inspired the HBO hit Game of Thrones. With no release date in sight, one tech-savvy fan decided to write the story himself, or rather, he asked ChatGPT to write it for him. Prompted to develop outlines for each chapter, and then turn those outlines into prose, the AI churned out a 683,276-word tome of surprising quality.

Surprising because although this “fan-made” version of Winds of Winter failed to live up to the standards of Martin’s work, it did contain the unexpected twists and turns that made his fantasy epic so successful. Among the book’s flabbergasted readers was Martin, who upon learning of its existence not only took legal action against the fan but also ChatGPT’s developer, OpenAI.

Joining the ranks of other bestselling authors such as John Grisham and Jonathan Franzen, Martin’s ongoing war with large language models — which were trained on their writing, among countless other sources — raises an important question about the creative capabilities of machine learning. Anyone who has used AI programs like ChatGPT in recent months knows they are great at summarizing textbooks and writing boilerplate cover letters, but can they also produce the kind of writing that moves us and speaks to our souls?

Training data

Journalist Vauhini Vara thinks the answer is yes. In an article titled “Confessions of a Viral AI Writer,” she relates how in 2020 OpenAI granted her early access to GPT-3. Defining creative writing mainly as “waiting for the right word,” she suspected that generative AI, with its instantaneous access to every noun and adjective in the English dictionary, could be a helpful tool, especially for topics she struggled to write about.

One of these topics — the topic, really — was the death of Vara’s older sister, who was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer while still in high school. Initially, GPT-3’s attempts at writing a story based on this premise were unsatisfactory. The AI would swap her sister’s real-world fate with a miraculous recovery or, in drafts where her death was acknowledged, turn Vara into a long-distance runner racing for charity. It wasn’t until she shifted to a more collaborative writing process, with GPT-3 learning from and adapting to her own inputs, that it managed to produce a line of text that genuinely touched her:

We were driving home from Clarke Beach, and we were stopped at a red light, and she took my hand and held it. This is the hand she held: the hand I write with, the hand I am writing this with.

Although ChatGPT has been programmed to write in a bland, explanatory way, it can learn to mimic other voices provided it has enough training data.

“I think there is a misconception that large language models like ChatGPT are not very good at writing in a lyrical, literary prose style,” author Sean Michaels tells Big Think after being pointed to Vara’s article. “In fact, they can do it easily and quite well, just like all the image-generating software can do things like making photos in the styles of Wes Anderson or David Lynch.”

For his novel Do You Remember Being Born, in which a poet is approached by a tech company to co-author a collection of poems with their AI, Michaels created a custom version of ChatGPT he called “Moorebot,” which through training learned to write in the style of real-world poet Marianne Moore, further blurring the distinction between human and machine.

AI: creativity and connection

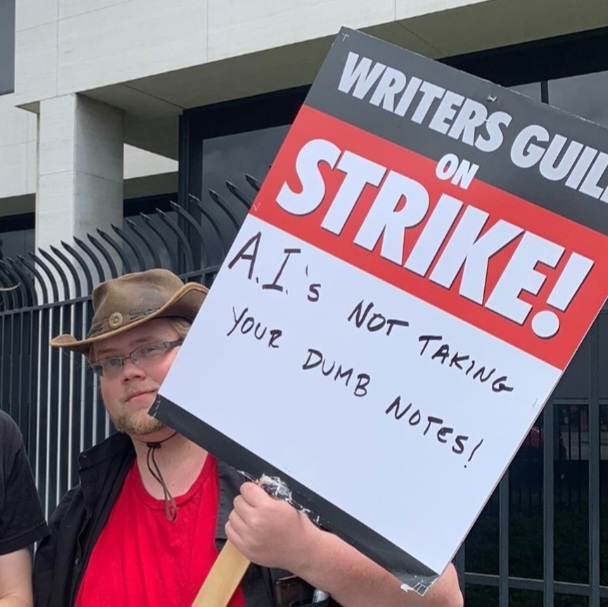

Although some writers oppose the rise of AI out of concern for their employability, others have embedded the debate in an older, broader dialogue on the meaning and purpose of art. The Oscar-winning screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, who writes in a style so idiosyncratic critics coined the phrase “Kaufmanesque” to describe it, has been perhaps most vocal about his personal distaste of machine learning. Looking beyond the standard definition of creativity — creating something new and original — Kaufman describes art as any form of expression that establishes an emotional connection between people.

“Say who you are,” he said in a BAFTA lecture that foreshadowed comments made during the 2023 SAG strikes. “Really say it, in your life and in your work. Tell someone out there — someone who is lost, someone not yet born, someone who won’t be born for 500 years. Your writing will be a record of your time. It can’t help but be. But if you’re honest, you will help that person be less lonely in their world.”

Even if AI were capable of writing something emotional or profound, which Vara and Michaels claim it can, Kaufman would refuse to recognize this as art because it cannot establish a link between reader and author. “If I read a poem,” he recently said in a statement on AI, “and that poem moves me, I am in love with the person who wrote it. I can’t be in love with a computer program. I can’t, because it isn’t anything.”

Kaufman’s sentiment should be assessed alongside that of Michaels who, through his work with AI, has reached a different conclusion: Human creativity is less special than we want to believe. He explains:

“Imagine I write, ‘The moon looked like a slice of lemon.’ You read it and think, ‘That’s an interesting image.’ But when AI does it, you think, ‘Well, is that interesting? Because it just seems completely random.’ Human beings have this capacity to make meaning from things and find connections where there are none or where there is no intention behind them. I found it provocative not just that AI could come up with lines I found beautiful or strange or interesting, but also that it got me wondering if the AI was doing something successfully as a writer or if I was doing something successfully as a reader.”

As for whether or not AI is capable of ‘true’ creativity:

“It’s true human art draws on memories, bodies, dreams, and arbitrary but somehow meaningful linkages between abstract, surreal thoughts. None of those things are things ChatGPT has. At least not in a literal way. But then again, there is something strange about the way fiction is about pretended bodies, pretended dreams, pretended lived experiences. If you read a modern story about, say, a 17th-century Dutch merchant, that’s not based on anybody’s real-life experience as a 17th-century merchant. Similarly, because these large language models don’t have what we have, that doesn’t mean that their work has none of the qualities that ours does. It’s not that easy.”

The future of writing

According to Michaels, increased usage of large language models is expected to lead “to a certain convergence of styles, with writing becoming less diverse and more monolithic as we use the same algorithms.”

Florent Vinchon, a PhD student at Université Paris Cité studying the creative skills of generative AI, suggests that — although it is still too soon to say with certainty — machine learning “might have the same impact on writing as photography had on painting,” a view shared by other experts in the field. Just as the camera pushed painters from realism to abstraction, spawning artistic movements that concerned themselves with how we perceive rather than what, AI could inspire new generations of authors to experiment with their writing.

Since programs like ChatGPT allow anyone to produce competent prose, the novels and novellas of tomorrow may be deliberately less polished, riddled with grammatical errors and linguistic idiosyncrasies that point to the limits of the human brain and the uniqueness of the individual perspective. Far from a threat to the survival of creative writing or human creativity in general, AI, like the innovative technologies that came before it, may become a force of change and a source of inspiration.

This article ChatGPT is great at summarizing books. But will AI ever write a true work of literature? is featured on Big Think.

The post “ChatGPT is great at summarizing books. But will AI ever write a true work of literature?” by Tim Brinkhof was published on 09/01/2024 by bigthink.com

Leave a Reply