Australia is among the world’s top three exporters of LNG and second-largest exporter of coal. When burned overseas, these exports result in 1.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions a year – almost three times Australia’s domestic emissions.

Emissions embedded in Australia’s exports do not count towards our national emissions targets. But they contribute to climate change – and they’re the reason for Australia’s international reputation as a fossil-fuel economy.

On the bright side, Australia boasts huge potential for low-cost renewable energy and a knack for resource industries.

We can, and should, become a “renewable energy superpower”. This term refers to the potential for Australia to use its bountiful renewable energy resources to make commodities such as iron, ammonia and other products and fuels in “green” or low-emissions ways.

So how does Australia give salience to this idea on the global stage, while our fossil fuel exports continue? The solution could be a new net-zero target for Australia, in which emissions from green exports are tallied up against those from fossil fuel exports.

Brook Mitchell/Getty Images

Reinvigorating Australia’s climate policy

If the clean energy transition eventuates, green exports from Australia will rise over time. This will help reduce the use of coal, gas and oil elsewhere in the world.

Meanwhile, coal exports – and later, gas exports – will fall. This will happen irrespective of Australia’s policies, as the world economy decarbonises and demand for fossil fuels slows.

At some point, we can expect emissions avoided by our green commodity exports to surpass those from remaining coal and gas exports. Australia would then reach what could be termed “net-zero export emissions”.

Adopting this net-zero target as a national policy would give a concrete yardstick to Australia’s green-export ambitions. It could also invigorate Australia’s climate policy and boost investor confidence.

A different approach would be to set targets only for green exports, and this could be how we get started. Ultimately, a net-zero target wrapping up both green and fossil-fuel exports would speak most directly to the goal of tackling climate change, and is likely to have more impact on the international stage.

Brook Mitchell/Getty Images

Getting to net-zero exports

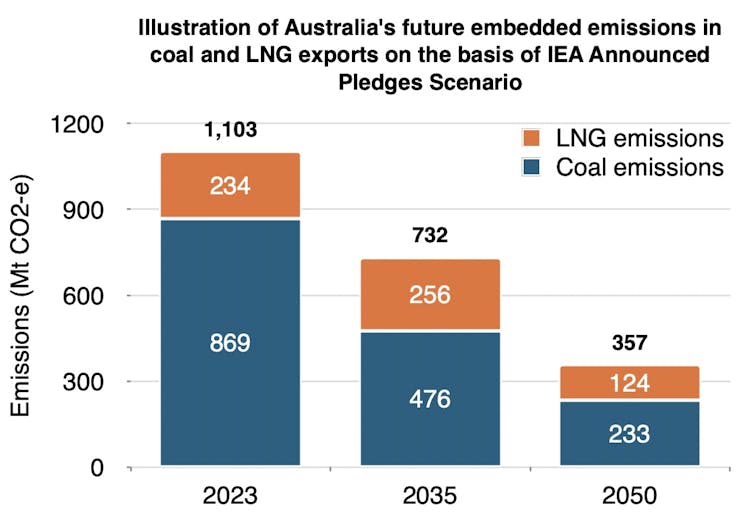

The below chart shows an illustrative decline in emissions embedded in Australia’s coal and LNG (liquified natural gas) exports, out to 2050.*

Authors’ calculations based on Australian Energy Update 2024, Australian National Greenhouse Accounts Factors 2024, IEA World Energy Outlook 2024

It’s hard to pin down when Australia might reach net-zero exports. It depends on several factors. How quickly will the cost of clean energy and green-commodity technologies fall? How competitively can Australia produce green goods compared to other nations? What policies will be adopted in Australia and overseas – and will they work?

The magnitudes are sobering. Take iron, for example. Australia currently exports 900 million tonnes of iron ore a year. This is processed overseas to about 560 million tonnes of iron.

To fully compensate for emissions currently embedded in Australia’s coal and gas exports, Australia would need to process about the same amount of green iron – around 550 million tonnes – on home soil every year.

To reach this figure, we assume 0.1 tonnes of CO₂-equivalent is created per tonne of green iron, compared to about 2.1 tonnes of CO₂-equivalent per tonne of iron resulting from conventional blast furnace production.

Achieving this would require keeping iron ore production at current levels and processing it all in Australia, which is unlikely to be realistic.

Thankfully, the task of reaching net-zero export emissions will be smaller in future, as global coal and gas demand falls. But exactly how this will translate to Australian exports is highly uncertain.

Dean Lewins/AAP

Let’s suppose Australia’s exports evolved on the same trajectory as they might under current climate policies and pledges for the global coal and gas trade.

In this case, embedded emissions from Australia’s coal and gas exports would be about 360 million tonnes in 2050. This includes about 120 million tonnes from LNG exports – much of it locked in by the extension to Woodside’s North West Shelf project off Western Australia.

Hypothetically, the 360 million tonnes of emissions could be negated by a mix of green exports. They include 102 million tonnes of green iron (saving 204 million tonnes of CO₂), and 11 million tonnes of green ammonia (saving about 23 million tonnes of CO₂), and the remainder covered by a combination of green aluminium, silicon, methanol and transport fuels.

Judgement calls would be needed about which commodities to include in the target. The composition of green exports suggested above is akin to assumptions about Australia’s potential global market share outlined by The Superpower Institute.

Importantly, it’s hard to predict with certainty the greenhouse gas emissions displaced elsewhere in the world by Australia’s green exports. So, the estimates should be understood as broad illustrations, and not as exact as the accounting used to calculate countries’ domestic emissions.

The precise year chosen for reaching a net-zero target for export emissions may well be less important than the commitment that, at some point, Australia’s green energy exports will exceed fossil fuel exports. This would establish the notion that Australia has the capacity and willingness to help the world decarbonise.

David Gray/Getty Images

A positive agenda for change

The export target could be part of Australia’s updated emissions pledge due to be submitted to the United Nations by September this year. The pledge, known as a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), is required by signatories to the Paris Agreement.

Each nation is expected to detail its national emissions target for 2035. But nations can make additional pledges towards the world’s climate change effort. You could call it an “NDC+”.

So Australia could outline an indicative goal for net-zero exports – perhaps alongside other pledges such as leveraging climate change finance for developing countries, or helping our Pacific neighbours adapt to climate change impacts.

As a large fossil fuels exporter, Australia would earn kudos for showing it has a positive agenda for change.

And if Australia wins the bid to host the COP31 climate conference next year, a plan to reduce export emissions could be a major rallying point.

* Underlying data for the chart showing an expected decline in future emissions embedded in Australia’s coal and LNG exports:

Exports in 2022–23: coal, 9.6 exajoules (EJ); LNG, 4.5 EJ, from Australian Energy Update. This was multiplied by an emissions factor 90.2 for coal (MtCO₂-e/EJ) and 51.5 for LNG (MtCO₂-e/EJ), as drawn from the Australian National Greenhouse Accounts Factors

Exports for 2035 and 2050: this assumes a trend aligned with the IEA’s Announced Pledges Scenario, as outlined in the World Energy Outlook 2024. Note the percentage changes from 2023 to 2035 and 2050 for coal (-45% and -73% respectively) and for LNG (+9% and -47% respectively.) These figures do not distinguish between steam coal for power and metallurgical coal.

Correction: an earlier version of this article said Australia was the world’s third-largest gas exporter. This wording has been amended to refer specifically to LNG, and to reflect that the order of the top gas-exporting nations changes from year to year.

The post “Australia could become the world’s first net-zero exporter of fossil fuels – here’s how” by Frank Jotzo, Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy and Director, Centre for Climate and Energy Policy, Australian National University was published on 06/17/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply