In southern Bangladesh, silt islands along the Jamuna River regularly appear and disappear. These ‘chars‘ are populated, despite the fact that they are completely flooded during the monsoon season.

Part of the great river Brahmaputra, the Jamuna river sees the emergence and disappearance of these ‘chars’ every year. The people who live here are known as the Chauras, and they have organized their lives around rise and fall of the waters. They go about their agricultural work and live in small communities, always knowing that everything they have built up can be destroyed with the coming of the monsoon season.

The film also documents the dry season, when the river Jamuna recedes, leaving long white sand beds and new islands of fertile soil. Chaura Rahim Shorkar has plenty to do now and hopes to harvest the crops in time for the next flood.

Rahim does not want to trade his life here for one on the mainland. His wife Alea, however, takes a more critical view. What future do they have here? What future awaits their six-year-old son Ashik?

At any moment, they could face the same fate as their neighbor Shuruz Saman, who has been hit for the sixth time in his life. All his fields and land have been swallowed up by the water and once again, making a new start costs him his entire savings.

All the Chauras know this suffering. They all help each other, lending a hand when the corrugated iron walls of their houses need to be moved again because of the waters. Life here is not easy and will not get easier. On the contrary, climate change is set to intensify the extremes of the monsoon and dry seasons.

#documentary #dwdocumentary #bangladesh

______

DW Documentary (English): https://www.youtube.com/dwdocumentary

DW Documental (Spanish): https://www.youtube.com/dwdocumental

DW Documentary وثائقية دي دبليو (Arabic): https://www.youtube.com/dwdocarabia

DW Doku (German): https://www.youtube.com/dwdoku

DW Documentary हिन्दी (Hindi): https://www.youtube.com/dwdochindi

Since the beginning of time, melting glaciers in the Himalayas have been feeding countless rivers. They pour out of the mountain range, running like veins throughout the South Asian continent. One of the most powerful is the Brahmaputra, which travels thousands of kilometres before crossing Bangladesh and flowing into the Bay of Bengal.

Here, the river is known as Jamuna. The Jamuna creates and floods many islands in its course. In Bengali, these ever-shifting island sandbars are called “Char”, derived from “Chora,” which means, “wandering”. The 3 million people who live on the islands call themselves “Chauras”. “But we don’t migrate,” they say, “the islands do.

We just have to wander along.” From June to September, during the monsoon, the river’s tides wash up fertile sediment that produces a bountiful harvest in the dry season. The floods provide both fish and joy to the Chauras. But they also take – gnawing at the shoreline of the old chars,

Flooding the islands, and causing pain. Like nomads, the Chauras move from flooded islands to newly emerging ones. But they are used to this. They know: The river gives them fertile soil on which they can grow and work again. A life of construction, destruction, and reconstruction. No fish. Nothing. Fishing is torture.

Oh dear. Didn’t you catch anything? It’s not bad. Careful, careful! That’s enough for lunch. 33-year-old Rahim Schorkar isn’t actually a fisherman, but a farmer. Together with his wife Alea Begam he feeds his 6-person household. Besides their two children, his younger brother and mother also live with them.

Rahim and his neighbours live on Char Rulipara, in the middle of the Jamuna. The monsoons began months ago, and the river is gnawing away at the islands. But the tidal waves that usually flood the chars are not here this year, even in August.

For us Chauras, the river is both a curse and a blessing. Here, where the Jamuna now flows, our Char Rulipara was actually everywhere. There were roads, schools, concrete buildings, we had everything. Then from the east the river started pushing and ripping everything away.

But right here a char could come up again and people could settle again. And over there, where our village of Rulipara is now, the Jamuna used to flow. Big ships used to pass by. I saw it myself as a child.

The Char Rulipara has now been stable for 12 years. But it is the exception. Rulipara is one of a dozen chars that make up the Gabshara Union district. Not all the islands in the district have reached such an age. Every few years, Jamuna washes away some of the chars,

Only to later wash up new sediment elsewhere. Not far from Rahim, until recently, lived Shur-Uz-Zaman Mia. There only water can be seen now because Jamuna has reclaimed large parts of his former home. Jamuna has taken over. Shur-Uz-Zaman, a farmer, lived here with his family for eight years.

Over here was my house. A piece of field was washed away with the property. Here was a house, over there was a neighbour, there was another, here was another friend of mine. Seven homes were here. The school that Shur-uz Zaman’s son attends must be demolished.

The water is only a few metres away from its foundation. The rubble will be reused, building material is precious. It’s not clear where the school will be rebuilt. For now, it remains closed. My son went to this school. My property is gone and now we are losing the school too.

This building you see here, we built it 6 years ago. Now we have to take it down again. Before, this school was somewhere else, then we had to take it down due to erosion and rebuild it here. Tens of times we’ve had to move with the school like this.

Monsoon season and erosion go hand in hand. You never know which island the river will take next. Nurpur perhaps? This char is only four years old. It doesn’t make a particularly powerful impression. But farmers who don’t have many fields often have no choice but to settle here. Come, follow your mother!

Amina Khatun lives here. She is married and has two daughters. Her husband Assir Uddin Khalifa is a farmer. Unfortunately, some of his fields have flooded and he’s no longer able to feed his family from field work alone. He also sells goods at the market.

We all have to live in a hut, with the animals. We are afraid of thieves or robbers because the river is so close. There are often river pirates here. We are poor, we have a few animals. If the thieves and robbers take that away from us, how will we survive?

Last time the water was up to here. Up to the waist. It was very difficult to live here. Then we moved to a neighbour’s house for a few days, and the flood hit us there too.

Then we had to build a rack up high to keep the animals away from the water. Often, we also slept on a boat. Rahim’s Char, Rulipara, is stable – for the moment. The people here still feel safe from Jamuna and its powerful tides. But even they are not completely safe from the floods.

That’s mine. I grew that myself. It’s grown well. This rice is brand new. Thanks to technical development, we can try new varieties. They grow very well. The yield is higher. When I was a child, you could only harvest a third of a field like this.

This char only came up from the river 12 years ago. But, well, people have become wiser. We plant trees immediately to anchor the soil. And we can eventually sell the trees later. This foundation, we built it in 2011. After that we had to wait until the earth settled.

When the water comes onto the property here, we have to bring extra soil here with the boat and then we build a hill, and then we put the animals on this hill. And for cooking, you can see the earth oven. Of course, it gets covered with water.

Then we build a high rack and on top of it, again, a new stove. We try to keep the wood dry and on top of it we sit and cook. I often tell him that maybe we should move to the mainland,

But he doesn’t want to leave the Char. He loves the Char more than anything. The mainland is out of the question for him. I tell her, why don’t you get some money from your parents? Why don’t you get 500,000 taka? We’ll buy a plot of land there.

But she can’t, she dreams of a house on the mainland. We just don’t have the money. Both Rahim and his wife Alea are busy all day. Like her husband, she’s educated. But here on the Chars, there’s no opportunity for women to put their schooling to use.

Alea supports her husband in his work and earns extra money as a seamstress. The neighbours buy their clothes from her instead of on the mainland. Because little harvesting takes place during the monsoons, many Chauras live off of fishing during the rainy season. But in recent years, the highly sought-after catch has been dwindling.

There are many different kinds of fish. And practised Chauras can even catch them with their bare hands. Look how big it is! The farmers no longer use the fish solely to feed their families. At the port of Gobindashi, they bring their fish to be auctioned off, supplementing their livelihood.

Rahim , too, sometimes visits the market in Gobindashi. Nothing for me there. Four hundred sixty. Four hundred sixty. Anyone 70? Four hundred seventy? Five hundred! Anyone five hundred fifteen? Five hundred fifteen?? Nobody? Then it’s gone for five hundred. Rahim brings the expensive fish home for supper.

Rahim can still trust that his land is safe from the rising waters. But not far away, it’s a different story. Shur-Uz-Zaman has given up his land and is storing parts of his house at his relatives’. Here are all the individual pieces of a complete hut.

And a few walls of another hut. I also put them on top. When we take down or rebuild the huts, it takes a lot of people. Logistically, it’s a big effort that also costs money. It is very tedious work. But we Chauras help each other.

If I decide to take down my house today and tell the neighbours, they come right away. If I hear that another neighbour is relocating, whether he tells me or not, I go there and help take down the hut, transport it away and rebuild it. All Chauras help each other like that.

Shur-Uz-Zaman and his family have to stay with relatives until they find a safe place for a new home. The river is rising. As unstable as the chars are, the land and farmland on them are still surveyed and entered into the land register.

All Chauras keep their title deeds in case their flooded land reappears. Perhaps this time Shur-Uz-Zaman will get lucky and Jamuna will give him back the land it took. This is what it looks like before the flood waters arrive. The green grassland is food for cattle.

But in order to cultivate the land, the grass has to disappear. Usually, the flood takes care of that. When it doesn’t, the farmers have to destroy the grass with chemicals in order to be able to plant. Jute is a particularly hardy crop, but it can only be grown in the rainy season.

There’s a reason it’s called the ‘golden thread’ of Bangladesh. It thrives, even when flooded. For the jute, water is a friend. It likes stagnant water, the more brackish, the better. After harvesting, the stalks must be left to soften in the water, so their threads can be pulled.

The remaining parts of the plant are used as building and burning material. A kilo of jute fetches about 1 euro. The farmers earn about 400 to 500 euros from the harvest. Significantly more than the 100-200 euros they would otherwise earn per month. With products like jute and rice,

The Chauras have adapted to the rhythm of the dry and rainy seasons. When it comes to electricity, they must also adapt to the rules of nature. Solar panels are easy to use and mobile. Until a few years ago, expensive oil was the only source of energy for the Chauras.

Today, children grow up with solar energy as the norm. For 6-year-old Ashik, it’s commonplace. Rahim’s brother Sharkar even runs his laptop off the panels. The computer is connected to the internet through his mobile phone. When you are done here, could you please weed the paddy field? Okay.

I have to go to a meeting. My brother graduated well from school. But farming is his great passion. He didn’t want to do anything else. And I want to work as a web designer from home. My brother supports me to learn this profession, to buy all this equipment. He supports me financially.

But I don’t have any training in web design. I follow the work of professional web designers in the country, even the internationally-known ones. I read their books, follow their blogs and YouTube videos. I think the young people on the chars are very smart. If I can get them together,

I would like to start a company here to provide services like this online. Unusually late, in early September, the tidal floods have finally come. Normally, the Chauras expect three tidal waves between June and the end of August. But this time the rising waters come only once. Here, too, climate change is evident.

Within a few days, the flood waters reach dangerous levels. As the river takes its toll, no one’s thinking about the fertile sediment it brings. Even though the floods will ensure a bountiful harvest for the Chauras in the coming dry season. The water has been standing here in the field for three days.

Seven days ago it started to rise. First the river was swollen. Then, in the last 3 days, the water entered here. If the water just continues to rise, all the rice will be lost. I don’t know if I’m lucky enough to save this rice crop. It’s grown so beautifully.

The water is close to our yard now. When the children play here, they could fall into a hole, it’s dangerous. I want to take a bath, Papa! No, you just had a shower. Well, that’s how it is, our life here. A few days ago we were walking on this path.

Everything was still dry. And now we are walking in the water. Sometimes the water comes up to our chests, or over our heads. Sometimes there is even a current here. Rahim seems relaxed about the flooding. Alea is more concerned. The ground near their home is still dry.

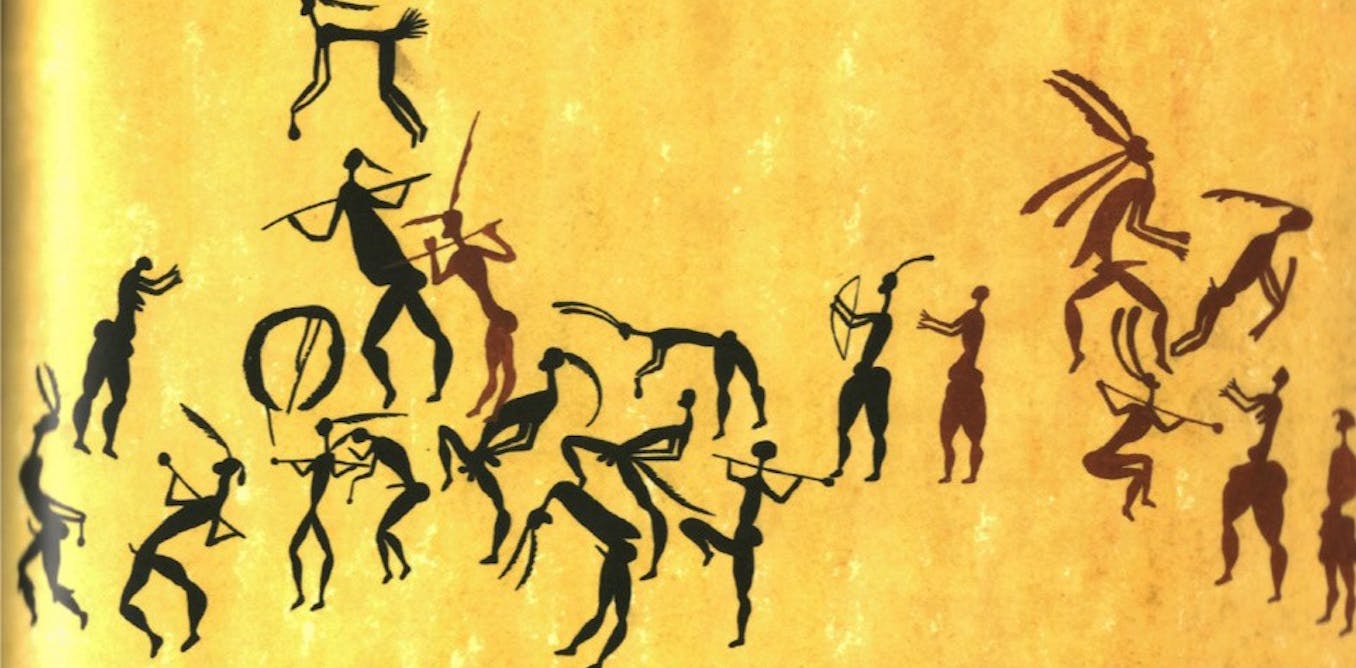

But if the water enters the yard, everyday life will become much more difficult. As evidenced in this footage from the past quarter century, the Chauras have had to develop extraordinary survival skills to adapt to the floods. Floods – which the Chauras say are increasingly worse due – only in part – to nature.

A bridge was built here 25 years ago, forcing the once 14-kilometre-wide river into a narrower channel. The Chauras say that until the bridge was built, the floods were not as dramatic as they are today. This time, there was only one tidal wave in the monsoon season.

It left behind huge amounts of fertile soil that had to be tilled. The dry season has long since begun. Now, 5 months later, it’s harvest time. Rahim was not lucky with his rice field. The water destroyed the crop. But he was able to save his other fields.

The landscape, which until now was a disaster area, suddenly looks very different. It now gives the impression one can live well here. It is a different world. But distances that could be covered quickly by boat or water taxi in the monsoon season now take much longer.

In the monsoon season, the water is overwhelming, now, it is scarce. But farmers desperately need it to irrigate their fields. The soil is still wet in some places and good for planting rice. Rice can be grown all year, but must be harvested before the floods come. It’s not just rice that grows here.

Throughout the dry season, the Chauras are busy harvesting one field after another. Groundnuts, maize, sweet potatoes, mustard and coriander keep Rahim busy. We don’t actually think there is a river here. All these floods are like a blessing for us. Because the more often the flood comes, the better it is for our farming,

The more we can grow. All this is just a river when the monsoons come. When it’s over, this is our farmland. These fields only lie unplanted for two or three months, just where they are flooded. Only during this time can we not cultivate. Then, everything is a river.

That’s why I think we live in the river, but it doesn’t feel like it. And our soil here has a big advantage: we don’t necessarily always need water for the plants. Sometimes you just see sand. For example, here, this soil. There, see how the peanuts are thriving.

But you can see how dry the soil is. Rahim’s neighbor, Shur-Uz-Zaman has been lucky. Rajapur Island has reappeared from the river. He owns a plot of land on it. The soil is nice and high, and it seems to be protected from the erosion that cost him huts and fields during the last monsoon.

Now he’s building the foundations for his new home here. It will need to be high enough to stay afloat during the next flood. Now we are moving from the Eastern to the Western side. We can actually make a good living from farming and agriculture. But this erosion is the problem.

For example, this house that I have to rebuild here, it will cost me almost a thousand euros all together. I could have saved this money. But I am forced to spend it. That is the problem for us Chauras. If every three or four years the river eats away at my property,

I cannot keep my savings. Even though there are no trees here yet to fortify the island, the new plot looks promising. The river is a safe distance away. Shur-Uz-Zaman planned the move ahead of time, and all the neighbours are pitching in. Things are looking good for Shur-Uz-Zaman at the moment.

But no one knows when Jamuna will get hungry again and start gnawing on the shoreline. Most of the Chauras are devout Muslims. Praying five times a day, however, is something very few do. But no farmer wants to miss the spiritual chanting at harvest time in late February. Have you been to school?

Yes, I saw the teacher. What did he say? He said I should study hard. I invited him to our house. Did you feed the cows? I think so, but check. You go abroad by plane. Abroad, that’s right. And what’s that? That’s a U.

A long U! Look, you see this raft here. Do you know what it’s made of? Banana trees! Right! What did they put on this raft? Sheep. And look at the girl, that’s the boy’s sister. See how scared she is. She’s afraid of falling into the water. But I’m not afraid of the water.

Char Nurpur has also survived the monsoon. But now, there is a lot to do in the fields. Amena’s husband Asir Uddin can take care of their younger daughter. He doesn’t have to travel far to work. This means Amina can take care of the older daughter’s schooling and have more time for housework.

My father was a cattle trader. As a child, he used to take me with him, so I watched him and learned how the business works. I ddn’t finish school, so I have to earn my money as a salesman. I managed a little bit. Until the seventh grade.

Then my parents married me off, so I couldn’t continue. We are poor Chauras. Girls get married off quite early. And when you’re married, you can’t go to school. Then you have to work at home. I would have had a good chance to finish school, my parents made an effort. But I blew it.

It’s like you are blind even though your eyes are healthy. The people who have education, they can see properly, they can understand everything and do a lot of things with their lives. Everything is much easier for them. And those who have no education at all,

They are like blind people with healthy eyes. That’s how it is. There are even people who can’t write their own name. I can home educate my children up to grade 7. I’ll take another bundle. No, no, no, that’s enough! One more! Wait until next time. Here! I want to take one more.

That’s enough. I want another one. You won’t make it. I will! The dry season has brought a good harvest and some security. The rice stalks are a precious commodity because they feed the most important thing of all – the animals.

They have to be stored up high so that the floods won’t reach them. Papa. Papa. Look! Look what I have here. My goodness! So much? Where do I put it? Bring it here, please. For 6-year-old Ashik, life on the char is still an adventure.

He doesn’t know what’s in store for the family. The monsoon season. With it, a time of uncertainty will begin again. Even though the family knows how to deal with the rhythm of nature, there is no secure foundation for an easy life. Alea knows that.

You have to cross the river here every time to bring in the harvest? That’s going to be hard again. Did you grow crops there last year? No, even further away. That was very exhausting. I don’t know yet how I’ll make it this year. Are you coming? No, I don’t want to. Why not?

It’s too far to walk! Why don’t you get some help? You know the women who work in the fields carry huge sacks of peanuts. They’re used to it. I’ve never done that. Why shouldn’t you? You can try it sometime. No, I don’t want to. I’m supposed to do everything myself or what?!

Who else? I was hoping that at some point we would live on the mainland so that the children could go to school. Do you have assets there on the mainland? Well, you don’t want to give up your fields here. You also quit your job in the city.

Just to plough on the chars all the time. But that’s not enough for a life. I guess you want me to toil alone in town and send you money so you can have a good life. Then keep digging in the sand! You don’t need a job. Tell that to your sons!

They should make money on the mainland and build a life there. I’ll stay here on the Char! Many Chauras think like Rahim. They may never give up this land. But two constants remain: the Char’s shifting nature and the Chauras desire for security.

Video “Bangladesh: Between monsoon and dry season | DW Documentary” was uploaded on 06/09/2023 by DW Documentary Youtube channel.