The UK’s environment minister Emma Hardy has announced a ban on toxic lead ammunition to protect Britain’s countryside. This ban includes the sale and use for hunting of both lead shotgun ammunition (each cartridge of which contains hundreds of small lead pellets called “shot”), used mainly for hunting small game animals like gamebirds, and large calibre lead bullets, used for hunting large game animals like deer.

This is great news for Britain’s birds because the ban will eventually prevent the deaths and suffering of the vast numbers affected by lead poisoning each year after ingesting lead from ammunition.

Most shot fired do not hit their targets and thousands of tonnes of lead shot are scattered in the environment every year.

Waterbirds and land-based gamebirds mistakenly eat these because they look like food or the grit they ingest to help grind up their food. Shot are retained in their gizzards (a muscular part of the stomach), ground up, and the lead dissolved and absorbed into the bloodstream.

Lead poisoning kills an estimated 50,000-100,000 waterbirds annually in the UK. These birds suffer considerably before they die. Many more birds are poisoned, but not killed.

While this additional “sublethal” poisoning does not kill birds directly, they may be more likely to die of other causes. This is because lead poisoning affects the immune system and behaviour.

AdamEdwards/Shutterstock

The use of lead shot for hunting waterfowl and over certain wetlands is already banned in England and Wales. It is also banned for shooting over all wetlands in Scotland.

However, compliance with the regulations in England is only about 30%, and is also low in Scotland, although has not been measured in Wales. This new comprehensive ban should dramatically improve the situation across all habitats throughout Britain.

Birds of prey, including eagles, common buzzards and red kites ingest lead fragments when they scavenge flesh from animals killed by lead ammunition, or prey on animals wounded by lead ammunition. The acidic conditions in their stomachs help dissolve the lead.

Our research shows that while fewer birds of prey than waterbirds are estimated to die of lead poisoning, it can have a far greater effect on their populations, especially for species that first breed at a later age, produce fewer young, and would otherwise have higher annual adult survival rates.

The lead ban will benefit birds that live in Britain permanently or for just part of the year. But it will not entirely solve the problem for migratory species. If lead shot continues to be used elsewhere, these species may still ingest it on migration or on their breeding or wintering grounds.

Beyond borders

To protect all species, lead ammunition needs to be replaced by non-lead alternatives everywhere. The use of lead shot is already banned in many wetlands globally. Across the EU, a ban on the use of lead shot in or close to wetlands came into force in February 2023.

Denmark was the first country to ban lead ammunition across all habitats. In 1996, it banned the use of lead shot and in April 2024, it banned lead bullets. Our research shows that the lead shot ban in Denmark has been very effective, with good levels of compliance.

Now, Britain is set to become the second country to ban most uses of lead ammunition. This has been made possible by the increasing availability of safe, efficient and affordable non-lead ammunition alternatives, primarily steel shot and copper bullets.

In February 2025, the European Commission published a draft regulation banning most uses of lead ammunition and fishing weights. This awaits approval under EU processes – if successful, it will represent a major step forward.

Beyond birds

Birds are particularly susceptible to the effects of ingested lead from ammunition due to their muscular gizzards and stomach acidity. But it also puts the health of many other animals at risk, including pets and people.

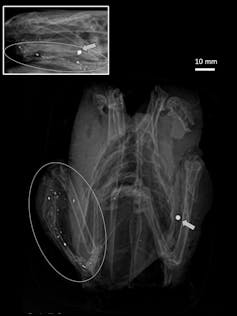

Rhys Green, Author provided (no reuse)

In the UK, we found average lead concentrations in raw pheasant dog food from three suppliers to be tens of times the legal maximum residue limit for lead in animal feed.

The UK government based its decision to ban lead ammunition on a report by the Health and Safety Executive which highlighted risks to the health of young children and women of pregnancy age if they frequently eat meat from game hunted with lead ammunition. Children’s developing nervous systems are particularly sensitive to the effects of lead.

We recently urged the EU’s committee of member states for Reach (the chemicals regulation), the European parliament and council to fully support the European Commission’s proposal to restrict lead ammunition.

We also encouraged the European Food Safety Authority to recommend that the European Commission set a legal maximum level for lead in game meat marketed for human consumption. This maximum level should be similar to the one already set for meat from most farmed animals.

Until this happens, and more countries follow suit by banning all use of lead ammunition for hunting, the health of wildlife, domestic animals and vulnerable groups of people will continue to be threatened by the toxic effects of lead from ammunition.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

The post “Britain’s ban on lead ammunition could save tens of thousands of birds from poisoning” by Deborah Pain, Visiting Academic, University of Cambridge; Honorary Professor, University of East Anglia, University of Cambridge was published on 07/18/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply