Supporting student mental health and well-being has become a priority for schools. This was the case even prior to the increased signs of child and youth mental health adversity in and after the pandemic.

Supporting student mental health is important because students of all ages can experience stressors that negatively affect their well-being and sometimes lead to mental health diagnoses.

However, some have suggested we can either support academic success or mental health — and that mental health is more important than academic achievement.

However, we can and should support both academic success and mental health — because they affect each other.

As a researcher who examines school-based mental health and also as a former school psychologist, it’s clear to me that one of the best ways to support mental health is to support academic development, especially early in children’s education.

Well-being in education

Well-being in educational settings involves all aspects of students’ lives: physical, cognitive, social and psychological functioning.

Education policymakers, schools and educators must attend to student well-being holistically rather than targeting one area at the expense of other areas.

A great deal of research shows that early academic performance predicts mental health and well-being. Most of the research showing this relationship between well-being and academic success is in the area of reading.

(Allison Shelley/ EDUimages), CC BY-NC

Recent reports from both Ontario and Saskatchewan human rights commissions highlighted the important role of strong reading instruction for student well-being, confidence and academic engagement.

Read more:

Reading disabilities are a human rights issue — Saskatchewan joins calls to address barriers

Stronger reading abilities, positive outcomes

In the example of reading and mental health, gaining reading skills increases positive student outcomes. Good readers report being more satisfied with their lives.

Later, they have fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression. Teachers rate students with strong reading skills as more prosocial and as having fewer behaviour problems.

These students are also more confident, have higher emotional intelligence and demonstrate more empathy. These positive outcomes are related to reading skill development, an important early indicator of academic success.

Poorer reading skills, worse outcomes

Being a poor reader, however, increases the risk for poor outcomes. Weak readers in early grades are more likely to have behavioural problems later. They also have poorer self-concept and self control, difficulty with relationships, shame, anxiety, depression, suicidality and delinquency.

Students who drop out of school are more likely to be poor readers, and poor readers are more likely to be involved with the criminal justice system. It is particularly telling that one of the best ways to keep youth from re-offending is to teach them to read.

Students with dyslexia

The relationship between dyslexia and poor well-being and mental health further reveals the interaction between academic success and mental health. Students with dyslexia, which is characterized by difficulties gaining reading skills, have more difficulty making friends, and having friends is an integral part of mental health.

They are also more likely to be bullied and to have low self-esteem. More specifically, having dyslexia increases the risk for also having anxiety, depression and behavioural problems.

Equity, reading instruction and well-being

Further, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are at greater risk both of not gaining adequate reading skills and of worse mental-health outcomes.

Language and literacy researchers Joan F. Beswick and Elizabeth A. Sloat contend that adequate access to strong reading instruction is a social justice issue. Their research, and other findings, document how students from poorer neighbourhoods are less likely to receive adequate reading instruction. This disproportionately puts them at risk for mental health problems that reduce their well-being.

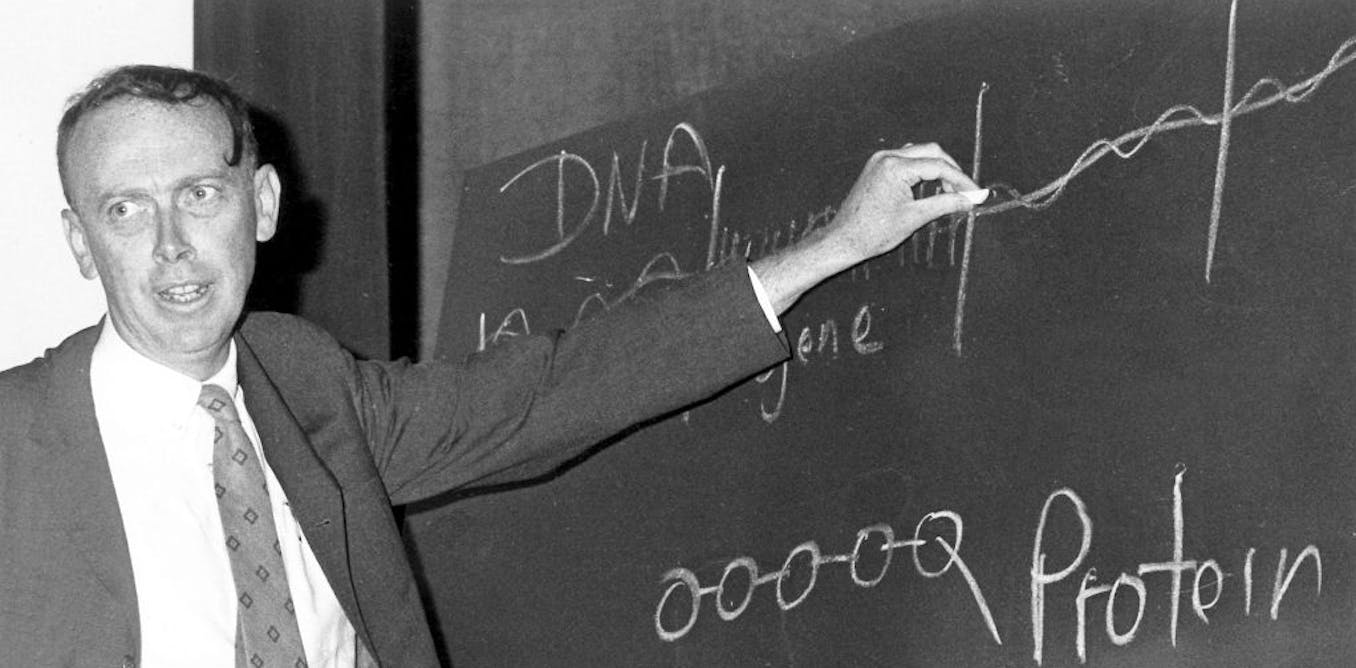

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Chris Young

The relationship between academic success and well-being is not limited to elementary school reading. High-school students who achieve academically also have better mental health.

A two-way relationship

It is important to note, nevertheless, that the relationship between academic achievement and mental health is bidirectional.

Some research shows that poor mental health, including behaviour problems, affect academic outcomes.

The relationship between academic success and mental health is complex and likely interactive with both poor achievement and excessive competition for high marks contributing to poor mental health. Academic performance and mental health each affect the other — either supportively or adversely.

Unhealthy academic competition

(Shutterstock)

Strong academic performance supports mental health and well-being, but unhealthy levels of academic competition negatively impact mental health and well-being. Reining in this unhealthy focus on intense academic competition is important.

Read more:

ClassDojo raises concerns about children’s rights

But only focusing on stressors of classroom competition in the relationship between academic performance and mental health could have adverse effects in the short- and longer term: It could reduce the mental health of students by not supporting healthy academic growth that promotes mental health and well-being.

It could also fail to teach students practices or habits required to navigate challenges with resiliency.

Need to support both

If we want to support student well-being and mental health, we need to support mental health directly by developing healthy school climates, teaching social emotional learning, and providing psychological services in schools.

But we also must support student academic success. This is the case especially as our most vulnerable students are at risk of both academic difficulty and mental health problems.

We don’t have to choose: we can and should support students’ academic success and mental health.

The post “Concerned about student mental health? How wellness is related to academic achievement” by Gabrielle Wilcox, Associate Professor, Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary was published on 01/08/2024 by theconversation.com