You might think good sleep happens in your brain, but restorative sleep actually begins much lower in the body: in the gut.

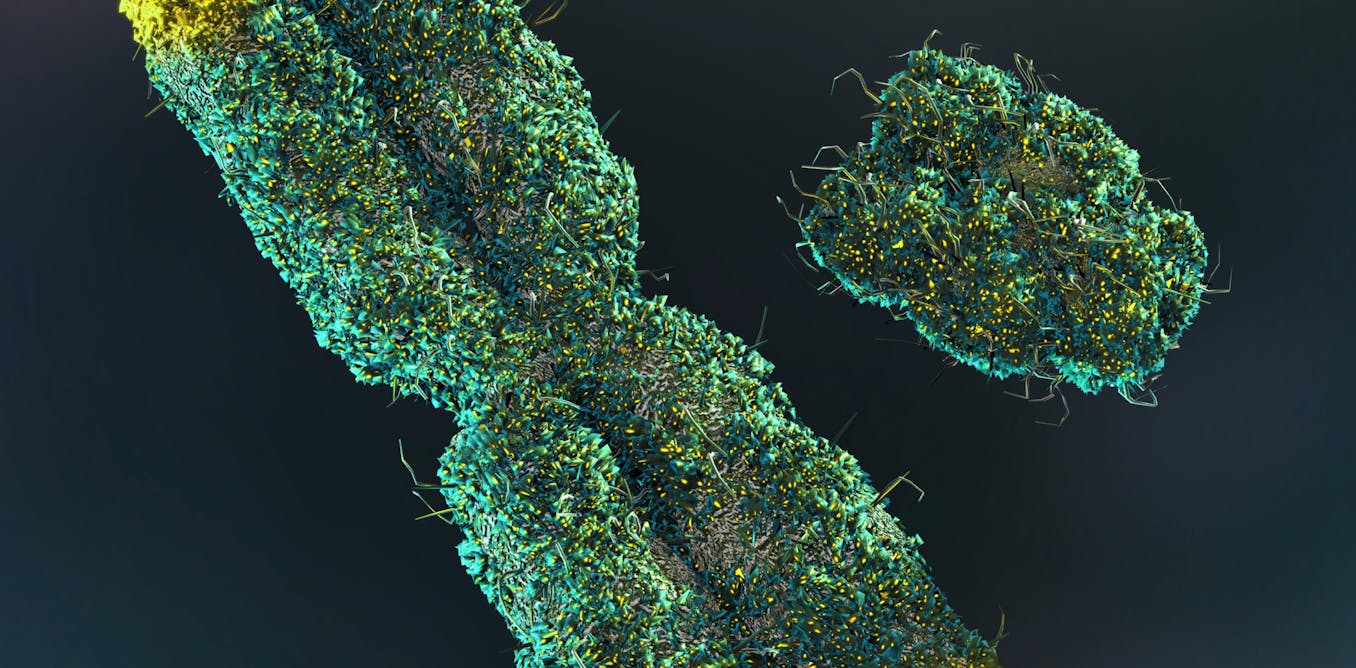

The community of trillions of microbes living in your digestive tract, known as the gut microbiome, plays a powerful role in regulating sleep quality, mood and overall wellbeing. When the gut microbiome is balanced and healthy, sleep tends to follow. When it is disrupted, insomnia, restless nights and poor sleep cycles often appear.

Gut and brain communicate constantly through the gut-brain axis. This communication network involves nerves, hormones and immune signals.

The best known part of this system is the vagus nerve, which acts like a two-way communication line carrying information between gut and brain. Researchers are still studying how important the vagus nerve is for sleep, but evidence suggests that stronger vagal activity supports calmer nervous system states, steadier heart rhythms and smoother transitions into rest.

Because of this intimate connection, changes in the gut influence how the brain regulates stress, mood and sleep.

So, how does the gut actually communicate these signals to the brain?

Gut microbes do more than digest food. They produce neurotransmitters and metabolites that influence sleep-related hormones. Metabolites are small chemical by-products created when microbes break down food or interact with each other. Many of these compounds can influence inflammation, hormone production and the body’s internal clock. When the gut is in balance, these substances send steady, calming signals that support regular sleep. When the microbiome becomes imbalanced, a condition known as dysbiosis, this messaging system becomes unreliable.

The gut also produces several key sleep-related chemicals. Serotonin, for example, regulates mood and helps set the sleep-wake cycle. Most of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut, and healthy bacteria help keep its production stable. Melatonin, which makes you feel sleepy at night, is made not only in the pineal gland but also throughout the digestive tract. The gut helps convert serotonin into melatonin, so its condition directly shapes how efficiently this happens.

The gut also supports the production of Gaba (gamma-aminobutyric acid), a calming neurotransmitter made by certain beneficial microbes. Gaba quiets the nervous system and signals that the body is safe enough to relax. Together, these chemicals form part of the body’s circadian rhythm, the internal 24-hour cycle that regulates sleep, appetite, hormones and temperature. When harmful bacteria dominate, that rhythm becomes less stable, which can contribute to insomnia, anxiety at bedtime and fragmented sleep.

Another major route linking gut and sleep is inflammation. A healthy gut maintains a balanced immune response. It does this by protecting the gut lining, hosting microbes that regulate immune activity and producing compounds that calm inflammatory reactions. If dysbiosis develops or a poor diet irritates the gut lining, gaps can form between the cells of the intestinal wall. This allows inflammatory molecules to escape into the bloodstream, creating chronic, low-grade inflammation.

Inflammation is known to interfere with sleep regulation. It disrupts the brain’s ability to coordinate smooth transitions between the stages of sleep because inflammatory chemicals influence the same brain regions that control alertness and rest. People with inflammatory gut conditions often experience this in very practical ways.

Irritable bowel syndrome, food sensitivities or increased intestinal permeability, often called leaky gut, all involve irritation or loosening of the gut lining. This allows immune-triggering substances to enter the bloodstream more easily, which increases inflammation and interferes with sleep. Inflammation also raises levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which makes the body feel primed for action rather than rest.

Stress, sleep and gut health continually reinforce each other. Stress alters the gut microbiome by reducing beneficial microbes and increasing inflammatory compounds. A disrupted gut then sends distress signals to the brain, which heightens anxiety and disrupts sleep. Poor sleep raises cortisol further, which worsens gut imbalance. This creates a cycle that can be difficult to break unless the gut is supported.

Strengthening the gut can make sleep noticeably better, and the changes do not need to be complicated. Eating prebiotic and probiotic foods, particularly fermented foods, supports beneficial microbes because fermentation creates live cultures that help repopulate the gut. Reducing sugar and ultra-processed foods lowers inflammation and prevents dysbiosis because these foods tend to feed bacteria that promote irritation or produce inflammatory by-products.

Keeping consistent meal times helps the gut maintain a steady daily rhythm because the digestive system has its own internal clock. Managing stress makes a difference. Staying well hydrated helps the gut microbiome because fluid supports digestion, nutrient transport and the mucus layer that protects the gut lining. Together, these changes create a more stable gut environment that supports deeper and more restorative sleep.

Good sleep does not begin the moment you climb into bed. It begins long before that, shaped by the health of the gut and the messages it sends to the brain throughout the day. When the gut is supported and balanced, the body is better able to settle, recover and shift into the rhythms that allow sleep to improve naturally.

The post “Good sleep starts in the gut” by Manal Mohammed, Senior Lecturer, Medical Microbiology, University of Westminster was published on 12/04/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply