It wouldn’t make much sense to prohibit people from shooting a threatened woodpecker while allowing its forest to be cut down, or to bar killing endangered salmon while allowing a dam to dry out their habitat.

But that’s exactly what the Trump administration is proposing to do by changing how one word in the Endangered Species Act is interpreted.

For 50 years, the U.S. government has interpreted the Endangered Species Act as protecting threatened and endangered species from actions that either directly kill them or eliminate their habitat.

Most species on the brink of extinction are on the list because there is almost no place left for them to live. Their habitats have been paved over, burned or transformed. Habitat protection is essential for their survival.

Steve Maslowski/USFWS, CC BY

As an ecologist and a law professor, we have spent our entire careers working to understand the law and science of helping imperiled species thrive. We recognize that the rule change the Trump administration quietly proposed could green-light the destruction of protected species’ habitats, making it nearly impossible to protect those endangered species.

The public, which has long supported the Endangered Species Act, has until May 19, 2025, to comment on the proposal.

The legal gambit

The Endangered Species Act, passed in 1973, bans the “take” of “any endangered species of fish or wildlife,” which includes harming protected species.

Since 1975, regulations have defined “harm” to include habitat destruction that kills or injures wildlife. Developers and logging interests challenged that definition in 1995 in a Supreme Court case, Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter of Communities for a Great Oregon. However, the court ruled that the definition was reasonable and allowed federal agencies to continue using it.

In short, the law says “take” includes harm, and under the existing regulatory definition, harm includes indirect harm through habitat destruction.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The Trump administration is seeking to change that definition of “harm” in a way that leaves out habitat modification.

This narrowed definition would undo the most significant protections granted by the Endangered Species Act.

Why habitat protection matters

Habitat protection is the single most important factor in the recovery of endangered species in the United States – far more consequential than curbing direct killing alone.

A 2019 study examining the reasons species were listed as endangered between 1975 and 2017 found that only 17% were primarily threatened by direct killing, such as hunting or poaching. That 17% includes iconic species such as the red wolf, American crocodile, Florida panther and grizzly bear.

In contrast, a staggering 81% were listed because of habitat loss and degradation. The Chinook salmon, island fox, southwestern willow flycatcher, desert tortoise and likely extinct ivory-billed woodpecker are just a few examples. Globally, a 2022 study found that habitat loss threatened more species than all other causes combined.

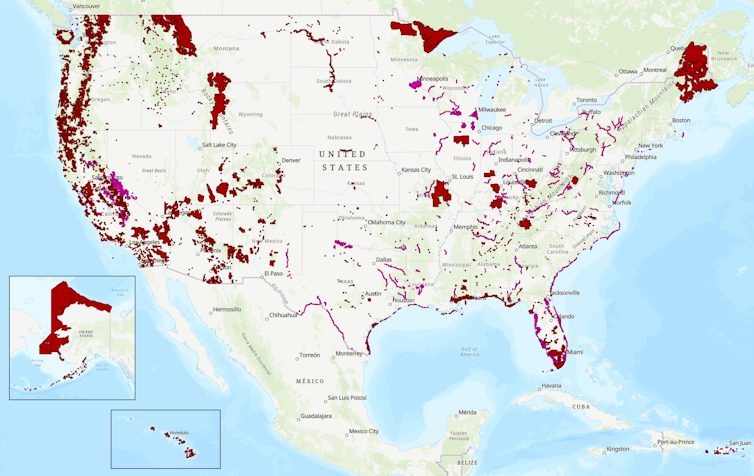

As natural landscapes are converted to agriculture or taken over by urban sprawl, logging operations and oil and gas exploration, ecosystems become fragmented and the space that species need to survive and reproduce disappears. Currently, more than 107 million acres of land in the U.S. are designated as critical habitat for Endangered Species Act-listed species. Industries and developers have called for changes to the rules for years, arguing it has been weaponized to stop development. However, research shows species worldwide are facing an unprecedented threat from human activities that destroy natural habitat.

Under the proposed change, development could be accelerated in endangered species’ habitats.

Gutting the Endangered Species Act

The definition change is a quiet way to gut the Endangered Species Act.

It is also fundamentally incompatible with the purpose Congress wrote into the act: “to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved [and] to provide a program for the conservation of such endangered species and threatened species.” It contradicts the Supreme Court precedent, and it would destroy the act’s habitat protections.

Tom Kogut/USFS, CC BY

Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum has argued that the recent “de-extinction” of dire wolves by changing 14 genes in the gray wolf genome means that America need not worry about species protection because technology “can help forge a future where populations are never at risk.”

But altering an existing species to look like an extinct one is both wildly expensive and a paltry substitute for protecting existing species.

Catalina Island Conservancy/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The administration has also refused to conduct the required analysis of the environmental impact that changing the definition could have. That means the American people won’t even know the significance of this change to threatened and endangered species until it’s too late, though if approved it will certainly end up in court.

The ESA is saving species

Surveys have found the Endangered Species Act is popular with the public, including Republicans. The Center for Biological Diversity estimates that the Endangered Species Act has saved 99% of protected species from extinction since it was created, not just from bullets but also from bulldozers. This regulatory rollback seeks to undermine the law’s greatest strength: protecting the habitats species need to survive.

Congress knew the importance of habitat when it passed the law, and it wrote a definition of “take” that allows the agencies to protect it.

The post “How redefining just one word could strip the Endangered Species Act’s ability to protect vital habitat” by Mariah Meek, Associate Professor of Integrative Biology, Michigan State University was published on 05/13/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply