When we think of Valentine’s Day, chubby Cupids, hearts and roses generally come to mind, not industrial processes like mass production and the division of labor. Yet the latter were essential to the holiday’s history.

As a historian researching material culture and emotions, I’m aware of the important role the exchange of manufactured greeting cards played in the 19th-century version of Valentine’s Day.

At the beginning of that century, Britons produced most of their valentines by hand. By the 1850s, however, manufactured cards had replaced those previously made by individuals at home. By the 1860s, more than 1 million cards were in circulation in London alone.

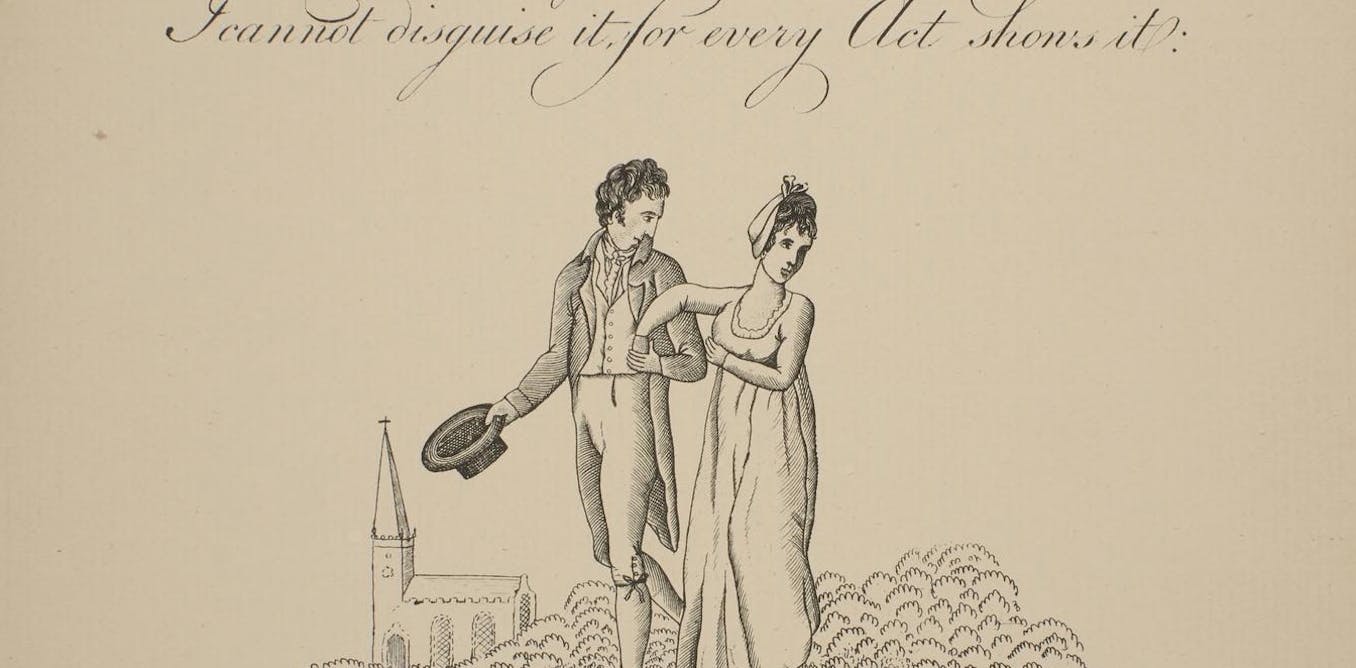

The British journalist and playwright Andrew Halliday was fascinated by these cards, especially one popular card that featured a lady and gentleman walking arm-in-arm up a pathway toward a church.

Halliday recalled watching in fascination as “the windows of small booksellers and stationers” filled with “highly-coloured” valentines, and contemplating “how and where” they “originated.” “Who draws the pictures?” he wondered. “Who writes the poetry?”

In 1864 he decided to find out.

Manufactured intimacy

Today Halliday is most often remembered for his writing on London beggars in a groundbreaking 1864 social survey, “London Labour and the London Poor.” However, throughout the 1860s he was a regular contributor to Charles Dickens’ popular journal “All the Year Round,” in which he entertained readers with essays addressing various facets of ordinary British daily existence, including family relations, travel, public services and popular entertainments.

In one essay for that journal – “Cupid’s Manufactory,” which was later reprinted in 1866 in the collection “Everyday Papers” – Halliday led his readers on a guided tour of one of London’s foremost card manufacturers.

Inside the premises of “Cupid and Co.,” they followed a “valentine step by step” from a “plain sheet of paper” to “that neat white box in which it is packed, with others of its kind, to be sent out to the trade.”

Touring ‘Cupid’s Manufactory’

“Cupid and Co.” was most likely the firm of Joseph Mansell, a lace-paper and stationary company that manufactured large numbers of valentines between the 1840s and 1860s – and also just happened to occupy the same address as “Mr. Cupid’s” in London’s Red Lion Square.

The processes Halliday described, however, were common to many British card manufacturers in the 1860s, and exemplified many industrial practices first introduced during the late 18th century, including the subdivision of tasks and the employment of women and child laborers.

Halliday moved through the rooms of “Cupid’s Manufactory,” describing the variety of processes by which various styles of cards were made for a range of different people and price points.

He noted how the card with the lady and gentleman on the path to the church began as a simple stamped card, in black and white – identical to one preserved today in the collections of the London Museum – priced at one penny.

A portion of these cards, however, then went on to a room where a group of young women were arranged along a bench, each with a different color of “liquid water-colour at her elbow.” Using stencils, one painted the “pale brown” pathway, then handed it to the woman next to her, who painted the “gentleman’s blue coat,” who then handed it to the next, who painted the “salmon-coloured church,” and so forth. It was much like a similar group of female workers depicted making valentines in the “Illustrated London News” in the 1870s.

These colored cards, Halliday noted, would be sold for “sixpence to half-a-crown.” A portion of these, however, were then sent on to another room, where another group of young women glued on feathers, lace-paper, bits of silk or velvet, or even gold leaf, creating even more ornate cards sometimes sold for 5 shillings and above.

All told, Halliday witnessed “about sixty hands” – mostly young women, but also “men and boys,” who worked 10 hours a day in every season of the year, making cards for Valentine’s Day.

Yet, it was on the top floor of the business that Halliday encountered the people who arguably fascinated him the most: the six artists who designed all the cards, and the poets who provided their text – most of whom actually worked offsite.

Here were the men responsible for manufacturing the actual sentiments the cards conveyed – and in the mid-19th century these encompassed a far wider range of emotions than the cards produced by Hallmark and others in the 21st century.

A spectrum of ‘manufactured emotions’

Many Victorians mailed cards not only to those with whom they were in love, but also to those they disliked or wished to mock or abuse. A whole subgenre of cards existed to belittle the members of certain trades, like tailors or draper’s assistants, or people who dressed out of fashion.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

Cards were specifically designed for discouraging suitors and for poking fun of the old or the unattractive. While some of these cards likely were exchanged as jokes between friends, the consensus among scholars is that many were absolutely intended to be sent as cruel insults.

Furthermore, unlike in the present day, in the 19th century those who received a Valentine were expected to send one in return, which meant there were also cards to discourage future attentions, recommend patience, express thanks, proclaim mutual admiration, or affirm love’s effusions.

Halliday noted the poet employed by “Cupid’s” had recently finished the text for a mean-spirited comic valentine featuring a gentleman admiring himself in a mirror:

Looking at thyself within the glass,

You appear lost in admiration;

You deceive yourself, and think, alas!

You are a wonder of creation.

This same author, however, had earlier completed the opposite kind of text for the card Halliday had previously highlighted, featuring the “lady and gentleman churchward-bound”:

“The path before me gladly would I trace,

With one who’s dearest to my constant heart,

To yonder church, the holy sacred place,

Where I my vows of Love would fain impart;

And in sweet wedlock’s bonds unite with thee,

Oh, then, how blest my life would ever be!”

These were very different texts by the very same man. And Halliday assured his readers “Cupid’s laureate” had authored many others in every imaginable style and sentiment, all year long, for “twopence a line.”

Halliday showed how a stranger was manufacturing expressions of emotions for the use of other strangers who paid money for them. In fact, he assured his readers that in the lead up to Valentine’s Day “Cupid’s” was “turning out two hundred and fifty pounds’ worth of valentines a week,” and that his business was “yearly on the increase.”

Halliday found this dynamic – the process of mass producing cards for profit to help people express their authentic emotions – both fascinating and bizarre. It was a practice he thought seemed like it ought to be “beneath the dignity of the age.”

And yet it thrived among the earnest Victorians, and it thrives still. Indeed, it remains a core feature of the modern holiday of Valentine’s Day.

This year, like in so many others, I will stand at a display of greeting cards, with many other strangers, as we all try to find that one card designed by someone else, mass-produced for profit, that will convey our sincere personal feelings for our friends and loved ones.

The post “How Valentine’s Day was transformed by the Industrial Revolution and ‘manufactured intimacy’” by Christopher Ferguson, Associate Professor of History, Auburn University was published on 02/12/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply