How can a desert burn? Australia’s vast deserts aren’t just sand dunes – they’re often dotted with flammable spinifex grass hummocks. When heavy rains fall, grass grows quickly before drying out. That’s how a desert can burn.

When our Karajarri and Ngurrara ancestors lived nomadic lifestyles in what’s now called the Great Sandy Desert in northwestern Australia, they lit many small fires in spinifex grass as they walked. Fires were used seasonally for ceremonies, signalling to others, flushing out animals, making travel easier (spinifex is painfully sharp), cleaning campsites, and stimulating fresh vegetation growth ready for foraging or luring game when people returned a few months later. The result was a patchwork desert.

After colonisation, this ended. Without management, the spinifex and grassy deserts began to burn in some of the largest fires in Australia.

But now the work of caring for desert country (pirra) with fire (jungku, or warlu) has begun again. We are Karajarri and Ngurrara rangers who care for 110,000 square kilometres of the Great Sandy Desert. Our techniques have changed – we now drop incendiaries from helicopters to cover more distance – but our goals are similar. Guided by our elders, we are combining traditional knowledge with modern technologies and science to refine how we manage fire in a changing world.

In research published today, we and our co-authors paired analysis of historic fire patterns with five years of fauna surveys. Put together, we found mature spinifex was important for creatures of the Great Sandy Desert – and that means we should burn small and often, like our ancestors.

Anne Jones

Fire and sand

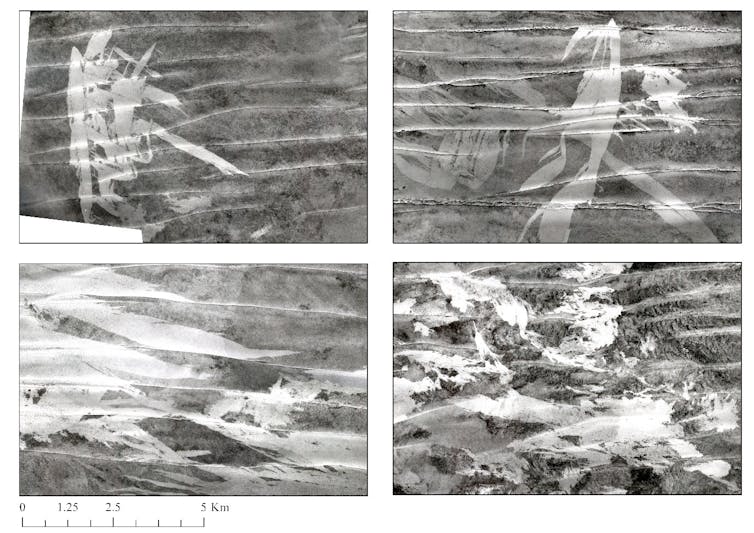

In the 1940s and ‘50s, the Royal Australian Air Force photographed the Great Sandy Desert from the air. These photos were taken before our people moved to settlements and pastoral stations between the 1960s and ’80s.

That means these aerial photographs capture a time when traditional burns were still happening.

Our ranger teams are studying these photographs to draw out the fire patterns produced by our ancestors.

These photographs tell a story. Our ancestors burned many small areas, creating a complicated patchwork of spinifex at different stages of regrowth after fire.

But they also left a great deal of mature spinifex – large old hummocks that hadn’t burnt for years. This patchwork of burned and unburned areas made it hard for bushfires to spread far and fast. When traditional burning practices stopped, bushfires became common.

The knowledge contained in these old photos is very valuable. The images give us clear goals for our fire management. We combine this with guidance from elders and information on fuel loads across Country gleaned from remote sensing and weather modelling, to plan our fire management.

National Library of Australia, CC BY-NC-ND

What does fire mean for desert creatures?

Australian deserts are remarkably biodiverse, especially in reptiles. In a single clump of mature spinifex, you might find up to 18 different species of lizard. Then there are snakes and goannas, as well as mammals such as marsupial moles found only in the arid zone.

Spinifex hummocks are crucial to many of these species, offering shelter, food and prey. What does fire do to spinifex-dwellers?

On this topic, scientific knowledge is playing catchup with Indigenous traditional knowledge but we see value in using the scientific method – a universal language – to help us manage Country, and tell other people about what we are doing.

The past few decades have been a time of major change for the Great Sandy Desert. Cultural burns stopped, and feral animals such as camels and cats grew in number. As a result, many native animals are disappearing or already gone.

Tom Sullivan/Yanunijarri AC: Karajarri KTLA

We think larger, more frequent fires play a part. Our Karajarri and Ngurrara rangers are using science to make sure our patchwork burns – known as right-way fire – are good for native animals.

Between 2018 and 2022, we surveyed reptiles and mammals from 32 sites across the Karajarri and Warlu Jilajaa Jumu (Ngurrara) Indigenous Protected Areas in the desert. We caught almost 3,800 mammals and reptiles from 77 species. Reptiles made up the lion’s share, with 66 species. We also recorded when fire had come through, and how big the burnt patches were.

The data showed reptile species care a lot about where they live. Some prefer recently burned areas, where the spinifex is gone or still very small. Others like old spinifex, huge hummocks going unburned for years. And others still liked mid-sized spinifex.

We found mammals were rare in recently burned areas and more common in mature spinifex. We also found more mammal diversity in areas with fine-scale patchworks of fires.

This shows we must keep our fires small, burning different areas at different times, and protect enough mature spinifex.

Karajarri Lands Trust Association; Yanunijarri AC; Anne Jones

This patchwork approach will help spinifex hopping mice, desert mice, planigales, dunnarts, and dozens of small reptile species to survive. But it will also help now-rare game species, the marlu (red kangaroo in Walmajarri language) and pijarta (emu in Karajarri).

Our research tells us returning to the traditional burning techniques of our ancestors is still the right thing to do – even though the desert has changed.

Rare finds

Scientists have rarely surveyed the Great Sandy Desert. As a result, our surveys have turned up important findings.

The kaluta (Dasykaluta rosamondae), for instance, is a feisty little carnivorous marsupial. We found it on the Canning Stock Route, 500km further north than the distribution known to scientists.

Similarly, we found the threatened Dampierland sandslider (Lerista separanda), a vividly coloured skink, in the Karajarri Indigenous Protected Area, expanding its distribution 450km southeast. Karajarri people call sandsliders winkajurta, or “lice eaters”, because in the old days you could use them to hunt lice in your hair.

Our research gives us confidence that bringing back traditional burns helps desert creatures. We want more people to know that right-way fire is part of healthy Country, including our own mob and tourists who pass through, so we can all look after the desert.

In our work, we take our old people out onto Country to get advice on burning and their knowledge of animals. As one told us, seeing the old ways return made him “real happy [and] to come alive” – just like the desert.

We thank Karajarri and Ngurrara Traditional Owners and acknowledge past and present elders. Thanks to the many rangers and coordinators who helped in these surveys, and our partners: Environs Kimberley, Charles Darwin University, Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, and Indigenous Desert Alliance. Special thanks to Hamsini Bijlani, our project coordinator.

The post “how we returned cultural burning to the Great Sandy Desert” by Braedan Taylor, Traditional Owner; Karajarri Lands Trust Association/UWA, Indigenous Knowledge was published on 10/10/2024 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply