Recently we have seen the launch of artificial intelligence programs such as SOUNDRAW and Loudly that can create musical compositions in the style of almost any artist.

We’re also seeing big stars use AI in their own work, including to replicate others’ voices. Drake, for instance, landed in hot water in April after he released a diss track that used AI to mimic the voice of late rapper Tupac Shakur. And with the new ChatGPT model, GPT-4o, things are set to reach a whole new level. Fast.

So is human-made music doomed?

While it’s true AI will likely disrupt the music industry and even transform how we engage with music, there are some good reasons to suggest human music-making isn’t going anywhere.

Technology and music have a long history

One could argue AI is essentially a tool aimed at making our lives easier. Humans been been crafting such tools for a long time, both in music and nearly every other domain.

We’ve been using technology to play music since the invention of the gramophone. And arguments about human musicians versus machines are at least as old as the self-playing piano, which came into use in the early 20th century.

More recently, sampling, DJ-ing, autotune technology and AI-based mastering and production software have continued to fan debates over artistic originality.

But the new AI developments are different. Anyone can create a new track in any existing genre, with mininal effort. They can add instruments, change the music’s “vibe” and even choose a virtual singer to sing their lyrics.

Given the industry’s longstanding exploitation of artists – particularly with the rise of streaming (and Spotify’s chief executive claiming music is almost free to create) – its easy to see why the latest developments in AI are frightening some musicians.

Music is a very human thing

At the same time, these developments offer an opportunity to reflect on why people make music in the first place. We have long used music to tell our stories, to express ourselves and our humanity. These stories teach us, heal us, energise us and help shape our identities.

Can AI music do this? Maybe. But it’s unlikely to be able to speak to the human experience in the same way a human can – partly because it doesn’t understand it the way we do.

It’s also unlikely to be able to create new works outside of existing musical paradigms, as it relies on algorithms taking from existing material. So we’ll likely still need our imaginations to create new musical ideas.

It also helps to note that music being controlled by “algorithms” actually isn’t a new concept. Mainstream pop artists have long had their music written for them by industry “hit makers” who use specific formulas.

It’s usually the musicians on the fringes, rather than the more commercial artists and products, who retain connection to music as a cultural practice and therefore push the development of new styles.

Perhaps the bigger question isn’t how musicians will compete against AI, but how we as a society should value the musicians who help create our musical worlds, and our very cultures.

Is this a task we’re happy to hand over to AI to save money? Or should such an important role be supported with job security and a fair wage, as is afforded to doctors, dentists, politicians and teachers?

Shutterstock

Art for art’s sake

There’s another much more fundamental reason why AI will not spell the end of human-made music. That’s because, as most musicians will tell you, making music feels good. It doesn’t always matter if it’s going to be sold, recorded, or even heard.

Consider mountain climbing as an example. Although we now have chair lifts, gondolas, funiculars, helicopters, planes, trains and cars to take people to the top, people still love climbing mountains for the mental and physical benefits.

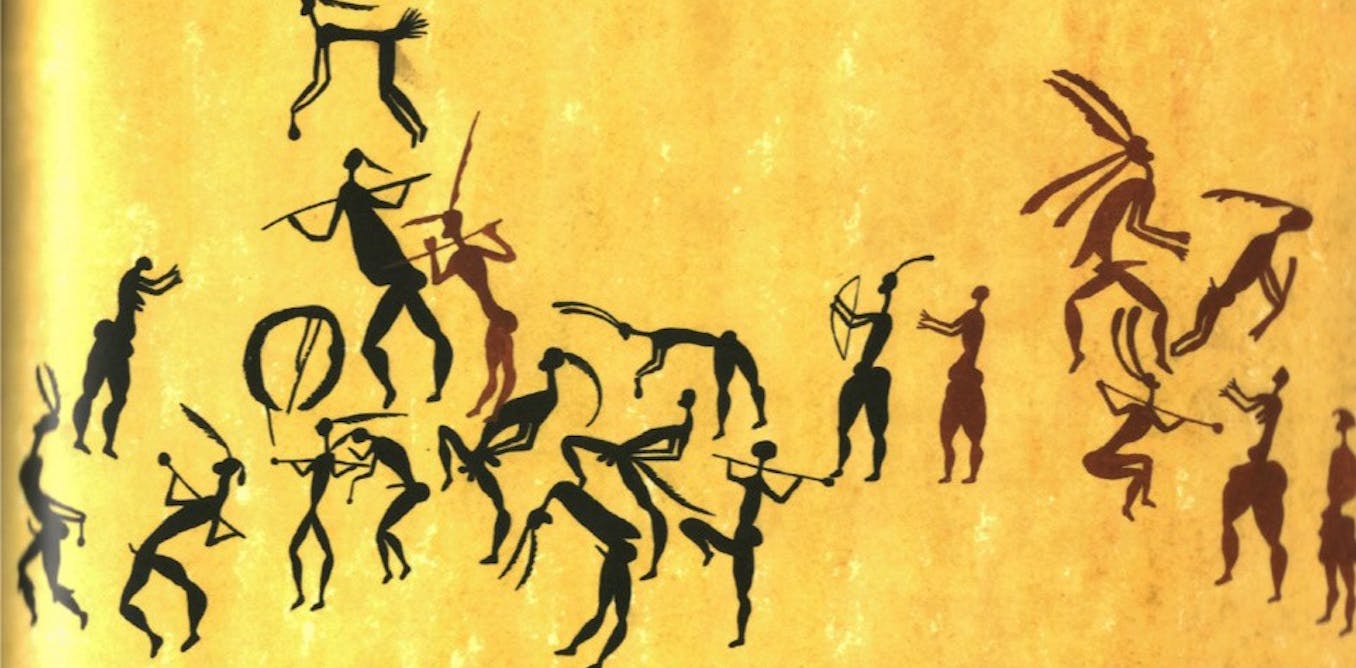

Similarly, playing music is a unique experience with benefits that extend far beyond making money. Ever since our ancestors first tapped rocks together in caves, music has connected us to others and to ourselves.

The health benefits are overwhelming (just look at the amount of evidence relating to choirs). The neurological benefits are also astounding, with no other activity lighting up as many parts of the brain.

No matter how good computers get at making music, active music engagement will always remain an important way to regulate our mood and nervous system.

Also, if our relationships with organic foods, vinyl records and sustainable fashion is anything to go by, we can assume there will always be a group of conscious consumers willing to pay more for human-made music.

AI as an opportunity

Further, while AI will likely disrupt the music industry as we know it, it also has amazing potential for boosting creative freedom for new generations of artists.

It may soften the separation between “musician” and “non-musician”, arguably allowing more people access to all the associated wellbeing benefits of music-making.

There’s also enormous potential for music education, since students could use AI to explore all aspects of the musical process in one classroom.

In a health context, personalised songs and albums could have significant implications for music therapy by letting therapists create tracks tailored to their clients’ needs. For instance, a therapist might want to produce a song a client has no prior association with, to avoid music-related triggers during therapy.

AI-assisted music is already being used in psychedelic therapy to create, curate and personalise people’s journeys.

Over the past 100 years, we’ve seen several innovations revolutionise the way we interact with music. AI ought to be understood as the next step in this process. And while change brings uncertainty, it also offers hope.

The post “No, AI doesn’t mean human-made music is doomed. Here’s why” by Alexander Crooke, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Music Therapy, The University of Melbourne was published on 06/11/2024 by theconversation.com