“Outrage culture” is pervasive in the digital age. It refers to our collective tendency to react, often with intense negativity, to developments around us.

Usually this ire is directed at perceived transgressions. The internet wasted no time in raging at Taylor Swift when she received Album of The Year at the Grammys, seemingly frustrated by her lack of acknowledgement of Celine Dion, who presented the award.

Whether or not Swift’s behaviour could be considered rude isn’t the point. The point is the backlash arguably wasn’t proportionate to the crime. This so-called “snub” incident is, therefore, a good example of how quickly and easily people will jump on the online hate train.

Modern outrage culture, which is also known as call-out culture and is linked to cancel culture, often devolves into a toxic spiral. People wanting clout compete to produce the meanest and most over-the-top commentary, stifling open dialogue and demonising those who make mistakes.

Read more:

How news sites’ online comments helped build our hateful electorate

A tale as old as time

Collective outrage isn’t a new phenomenon – nor is it necessarily bad. Humans have adapted to become highly sensitive to the threat of social exclusion. Being called out hurts our feelings, which motivates us to change. We learn how this feels for us and we learn how to use it to influence others.

In pre-digital societies, expressing outrage to shame someone as a group served crucial social functions. It reinforced group norms, deterred potential rule-breakers, and fostered a sense of order and accountability within communities.

Expressing outrage can also challenge norms in a way that leads to positive societal change. The women’s liberation movement in the latter part of the 19th century is a good example of this.

The technological innovations of the internet, smartphones and social media have now enabled communal outrage on a global scale. Multiple societies can be affected at once, as witnessed with the #MeToo movement.

When outrage spirals

We’ve all seen it play out. Someone says or does something “controversial”, some posts draw attention to it and soon enough a whirlwind of comments appears, echoing over and over the person in question is fundamentally bad.

The Johnny Depp and Amber Heard defamation trial is an example where, regardless of how you feel about the case, it’s hard to deny the discourse turned toxic.

The collective moral outrage that drives such negativity spirals has parallels with people brandishing their pitchforks during the 1690s Salem witch trials. Sharing similar beliefs helps us feel like we’re part of the group.

Beyond that, the conviction we witness in others’ comments and behaviour on an issue can stir up our own emotions, in what’s called “emotional contagion”. With our own emotions heightened and our convictions strengthened, we may feel compelled to join the choir of negative discourse.

The overall tone and style of language used by others can also influence how we act and feel. Social modelling dictates that if many others are piling on with negative comments, it can make it seem okay for us to do so, too.

And the more exposed we are to one-sided discourse, the more likely we are to resist alternative viewpoints. This is called “groupthink”.

Social media algorithms are also generally set up to feed us more of what we’ve previously clicked on, which further contributes to the one-sidedness of our online experience.

Scholars have suggested algorithms can prioritise certain posts in a way that shapes the overall nature of commentary, essentially fuelling the flames of negativity.

Read more:

Feed me: 4 ways to take control of social media algorithms and get the content you actually want

Two sides of speaking up

Unlike Salem in the late 1690s, today’s outrage culture is multiplied in intensity and scale due to changing cultural norms around “speaking up”. Combined with the anonymity and global reach afforded by the internet, the culture of speaking up has likely fuelled the kind of vocalisation we see online.

For example, in the past two decades there has been growing societal recognition that it’s good to speak up against bullying. This can be associated with more education on bullying in schools. There’s also a growing trend of encouraging a speak-up culture in workplaces. So it’s not surprising many people now report feeling confident in voicing their opinions online.

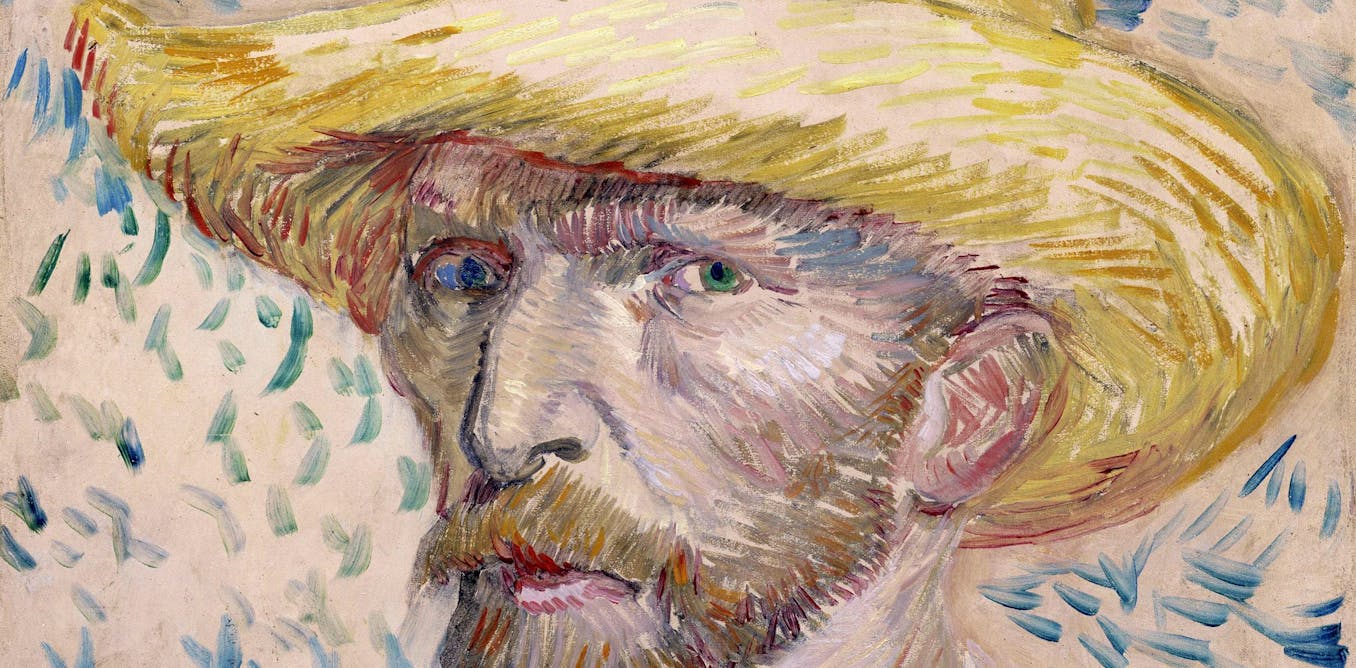

Shutterstock

It’s also easier to express negative opinions online since we can remain anonymous. We don’t directly witness the emotional pain inflicted upon our target. Nor do we have to worry about the potential threat to our personal safety that would be associated with saying the same horrible thing to a person’s face. As summed up by Taylor Swift herself in You Need to Calm Down:

Say it in the street, that’s a knock-out. But you say it in a tweet, that’s a cop-out.

How can we combat negativity?

Navigating the pitfalls of outrage culture requires us to adopt a more reflective approach before participating in public condemnation. Consider also that outrage culture runs counter to the moral ideals most of us admire, such as:

- everyone makes mistakes

- people are worth more than their worst actions

- people are capable of growth and change, and deserve second chances

- it’s okay to have different opinions to others

- the punishment should fit the crime.

Research suggests positive comments can be a productive counter-influence on negativity spirals. So it’s worth speaking up if you do witness matters getting out of hand online. Before clicking the send button, consider asking yourself:

- do I really believe what I’m about to say or am I going along with the group?

- how might this comment affect the person receiving it, and am I okay with that?

- would I communicate like this if it was a face-to-face situation?

By encouraging reflection, empathy and open dialogue, we can avoid toxic outrage culture – and instead use our collective outrage as a force for positive change.

Read more:

We cannot deny the violence of White supremacy any more

The post “Outrage culture is a big, toxic problem. Why do we take part? And how can we stop?” by Shane Rogers, Lecturer in Psychology, Edith Cowan University was published on 02/22/2024 by theconversation.com